On Saturday October 13, The Art Life were lucky enough to be guests of ARC – Art, Design & Craft Biennial 2007. We were invited to speak on a panel discussion called The Cult of The New. Here is an edited version of our presentation…

The contemporary art world runs on the fuel of the new. We need it to power our conversations, to push the next thing forward, to define ourselves against the forces of reaction. The new is an ideology, a descendant of the Enlightenment, a grandchild of Modernism.

Yet we’re also deeply ambivalent about the new, perpetually worried that it’s nothing more than a fad or a craze, a superficial fascination that will fade away just as soon as the next thing arrives.

Let’s discuss a few aspects of the new. Some of them are related to the art world, some are more personal, others are about the bigger picture, about how these ideas of the new inform how we think and feel and act in the world.

So let’s start there, in the bigger picture and something that’s on a lot of people’s minds.

Very soon we’re going to be voting in a Federal election. There will only be one of two probable outcomes. A vast amount of time and resources are being expended on thinking about and discussing what the ramifications will be if one or the other of those options come to pass. The election will be a point from which the future of this country will head in one of two directions. Those directions are largely speculative, but one of the interesting aspects of this future event is that one side of the debate brand themselves “New Leadership.” The idea is to evoke newness as a concept of possibility over and above the concept of continuation. Newness is invoked as a future state under which we will be potentially happier with more possibility. This future state we’re heading towards is emblematic of certain aspects of the new – the new as a looming change, a speculative mind state about which many are hoping on a certain outcome.

This pre-election scenario also highlights other aspects of the new. One is the uncertainty we feel about what the future will bring; the other is the frustration that the future hasn’t arrived yet. In this sense newness is also a state of anxiety.

We were recently doing some freelance work for an advertising agency that is producing political ads for one of the parties. One ad they did had nothing more than text on a coloured background, but there was a great deal of discussion about what certain fonts meant and whether that meaning changed when the font was placed on different coloured backgrounds. Copperplate on a blue background as opposed to Helvetica New on a blue background? Should that be a rich deep blue, or an airy sky blue? The thing is, the minutiae of the ad and the type and the background all carried particular meanings that would be understood by various test audiences. In this case, the familiar was needed for the message to succeed.

Newness is a diverse state that is implicitly political.

The features of the new are fairly easy to recognise since we are so attuned to the familiar. Like those test audiences who will be asked to respond to something they already know, the implications of a set of understood variables are of limited interest. It’s only when two or more already known things are put together in an unexpected way that we encounter an authentic kind of newness.

In the art world, newness is nearly always a combination of things that already exist.

Take video art for example. Over the last couple of years there has been an increasing awareness in the general media that video art has become popular. By extension it’s often said video art is new. Of course, that’s nonsense. Video art – a vast, hard to define variety of art practices – has been around since the early 1960s, and even earlier if you extend the definition to include artists’ use of TV in the 1950s. So how could anyone say that video art is new?

What’s changed, and what gives video art an aura of newness, is that it exists in a different context. The proliferation of affordable video production equipment has meant that artists can make a video for comparatively very little. Where video art was once the province of artists with access to expensive equipment, now anyone with a Mac and iMovie and a DVD burner can get a show at an artist run space.

The general media can be forgiven for mistaking video for something that’s new, because on a greater time line compared to drawing or painting it is relatively new. But in the strictest sense, video art just seems that way – it’s more visible and more distributed. To say its new is shorthand to say it has been admitted to a different order of consideration.

The title of this session is called Cult of The New. To be part of the new, to advocate it, is to believe that newness is worthwhile. It has cultish qualities and the information of what is new, or said to be known, is passed around, an information commodity.

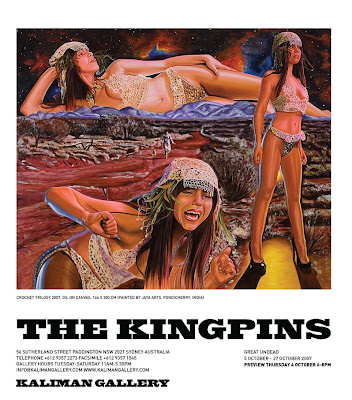

As writers we are often asked to help keep this economy going by writing about people or things that are new. What’s interesting about this aspect of newness is the way certain artists come to embody the idea while actually being quite the opposite. Ben Quilty, for example, has made a name for himself as a deft and precise painter, his big thick impasto works mining Aussie culture for its imagery. Or perhaps the King Pins whose performances, videos and paintings provide a commentary on Australian middle class values while ironically mocking them. Or maybe Shaun Gladwell, whose formalist videos conflate drawing and dance and movement into hypnotic, repetitive screens.

All of these artists have enjoyed degrees of celebrity over the past few years, yet none of them are particularly new in the sense that what they are doing is unprecedented. All their work is accountable; all of it is connected historically, it comes from an explicable context. But more than that, all of these artists and their work are supported and promoted within the art world not because it’s new, but because it’s old. These artists represent a tradition of thinking, a desire to create newness, not exactly an institutionalised avant garde, but an ongoing commitment to the new even if it is paradoxically old.

And that is the weird thing about the new in the art world – we are both accepting of the new, acutely self aware that it’s pointless in a way, and willing to entertain it as a notion at least for a short while, yet reject the new as the new becomes dominant. We replace the new with something more new, even when, again, paradoxically it’s not.

There are a number of factors working together to create newness in the art world. One is the subjectivity of an artist. You never can tell how an individual is going to synthesise influences. Another is the audience that looks around for something different. Another is the market forces that push the idea of newness to create novelty and exoticism and sell the idea of the new back to the audience.

So is it possible for there to be anything really, genuinely new? Let’s take a longer view.

We were born in the early 1960s at the tail end of the baby boom. For the first eight years of our lives, the western world was enraptured with the space race. Everywhere you went, there was talk about space. At school, on the bus, in the newspapers, on TV. Corn Flakes and Coco Pops cereal packets came with plastic moon landers and Saturn V rockets, there was a afternoon TV show hosted by an astronaut, every other movie was about space and the only good things on TV were Star Trek, Captain Scarlet and UFO. That was an incredibly optimistic side of the Cold War. There was a real war going on and the world, yet the idea that we were about to step into space was actually taking place. It was real. And it reeked of the new.

We think back on that time as adults and wonder whether we were was duped by Cold War propaganda or whether people really did feel those things. They must have because everyone certainly acted as if they did. As that sense of newness faded away, space became Star Wars and no one was actually on the moon.

Despite the fade, the technological imperatives of the Cold War and the space race filtered out into the public sphere and became integrated into our lives. Throughout the 1960s and 70s – and even into the 80s – there was a semi-regular feature in the newspapers and magazines where a journalist would ask; what will life be like in the year 2000? We remember one feature about how, in the future, you’d be able to go into a shop and use a plastic debit card to buy your groceries rather than use cash, or how, one day, you’d be paid electronically instead of waiting for a brown envelope stuffed with cash and coins to come from the pay office. It all seemed amazingly exotic.

This stuff is incredibly old hat, an antique type of new. But what’s significant about the technological imperatives of the mid-20th century is that they did change the way we live. It could be argued that the driving forces of our lives remain significantly the same, yet we are now being faced with variations of the past that are new – the web, social networking, an even higher integration of technology. These are genuinely new things, yet we are actually attuned to accepting that sort of newness because the last 50 years have primed us to accept innovations as just another part of the landscape.

The long range view of how things come along and change the way we live our lives is the only one that actually demonstrates that there can be new things. The smaller stuff, the pop cultural and art world newness are more like window dressing on the big picture analysis of the new.

While we were writing this essay we discovered fururetrendsgroup.com the website of a professional trend forecaster, a “business futurist”. His web site has a downloadable PDF of a big chart that traces trends from 1740 to 2100. There are three connected graphs – social, technical and economic. According to this graph, from here until the end of the century, we can look forward to the end of petroleum, the rise of fusion power, massively complex, distributed and sophisticated information processing, nanotechnology and biotechnology becoming the key drivers of the next 93 years. Interestingly, the part of the graph that charts social and economic trends is blank.

We mentioned that the idea of the new is political and discussed the advertisement where everyone at the agency was agonizing over what font and colour to use. It would come as no surprise to you that the final decision was totally predictable. But let’s say that they had decided to use, instead of Helvetica new on a mid-blue background, a gothic script on a tartan background… That kind of political ad simply would not have been taken seriously because it would have disrupted too many preconceptions about what a political ad is supposed to be.. Take the GetUp climate change ad that was run on TV recently. Hardly anyone realised it was a parody because it was so closely styled on a real political ad. It looked completely authentic. That’s an example of the old becoming so familiar that the message is lost in the medium.

The traditionalist, quality driven world of art – the world that runs parallel to contemporary art – is a world that has a lot of allure. History and tradition is deep grain, rich and inviting. The new, fashionable avant garde – it could be argued – is like Formica, a plastic that looks great at a distance but which lacks detail close up. But the problem with traditionalist view is that art becomes a generic expression – the individual artist is judged on how they deploy a set collection of cues within a limited range of expressive possibilities.

Contemporary art on the other hand – and the concept of the new – about disrupting those possibilities. These things do not go together, these colours are wrong, this art is ugly, it has no meaning – all of these are expressions of the new. They are the gothic script on the tartan background of the world. The idea of progress is a discredited notion yet without it at some level, art becomes moribund. We need the new to fill in that huge blank nothing of the future. That’s what the new is. And we like it.