Where have we been? Unfortunately we can’t tell you. Let’s just say that we have been working to make the world a better place, free from sadness and want, indeed, a broadband nation dedicated to education and the advancement of, you know, whatever… Our mission has taken us to Brisbane there times, once to Adelaide and innumerable trips around Sydney. None of this will make sense to you now but take our word for it – it will very soon.

We have seen some art and some it was good too. The exhibition Cross Currents on at the Museum of Contemporary Art is the third in their series of shows featuring the work of mid-career artists. This one has been curated by John Stringer and has the advantage over its predecessors of being good. Yes, it’s true, it’s a far more conservative selection as far as the kind of art on show – lots of painting, a tiny bit of sculpture, photography and installation – but what a refreshing change. The smell of paint wafts through the MCA like baking day at the bread shop. Mmmm.

Elisabeth Cummings is an artist who a lot of people that like good quality art really admire. And we admire her work too because whenever we look at it, you can just feel the goodness and the quality oozing off the canvas, or in the case of the works in Cross Currents, wafting off the oil based inks on paper. Ah Xian’s celebrated ceramic heads – the Bust series – offer a similar sort aesthetic reassurance. Both artists’ work is like taking some money you won at the track and investing it in real estate.

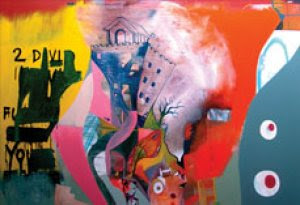

Gareth Samson, The Keep [detail], 2004.

Oil and enamel on linen.

Private collection.

Two artists work who we haven’t given much thought to for a long time are Gareth Samson and Dale Hickey. Samson kept entering garish and unlovable photos into the Citigroup Photo Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW, yet kept producing supple paintings for that benighted Sulman comp. His big paintings in Cross Currents marry both strands of his practice and we can say this about Samson; he’s a dirty, dirty, dirty boy. If he isn’t dolled up in leather he’s got a lady’s part between his legs. Doesn’t he know the MCA is a family institution? Hickey’s work meanwhile shows that artists can get a second, third or fourth wind and make paintings just as alive and vital as they did 40 years ago.

Glenn Sloggett, 666, 2006. Type C Print.

Courtesy Stills Gallery. Copyright the artist.

Across town at Stills Gallery Glenn Sloggett’s solo show Decrepit finds the artist making an unexpected trip out into the country, but just like his big city work, he finds the same bleak ennui in tree stumps as he finds in Melbourne shop windows. As beautiful as they are despairing, the quietness of the work is overwhelming. The show’s saving grace is its sense of humour. Like his stable mate Roger Ballen, Sloggett’s stock in trade are surrealist shocks that trip you up every time no matter how familiar they feel. Perhaps it’s that very familiarity that creates the fuel for the images. When we went to interview Sloggett for The Art Life TV show, we had imagined the artist to be a Shaun Gladwell-esque skater who maybe took his shots with an expensive digital camera, perhaps selling editorial work to the likes of Vice. How wrong could we have been? Instead, Sloggett had a framed poster of Ran on the wall and a DVD of Barton Fink on the coffee table. He’s living the dream.

Shaun Gladwell, Woolloomooloo Night [Production still], 2004.

Courtesy the artist and Sherman Galleries.

Speaking of Shaun Gladwell, you may have noticed the artist is having a major show- In A Station At The Metro – at Artspace. The show got a glowing write-up by Sebastian Smee in last weekend’s Australian. The review was remarkable for two things – Smee got through the entire thing without mentioning Matthew Barney, his favourite all-purpose point of reference for video and performance art – while he waxed lyrical about the associations of the exhibition’s title – noting the lift from a poem by Ezra Pound – but neglecting to mention anywhere that Pound, an expatriate American who lived in Italy before and during World War 2, was both an apologist for Mussolini and an arch anti-Semite.

We mention these unsavory facts about Pound because no one else seems to have thought it apt to do so in relation to Gladwell’s work, and not in keeping with the usual litany of reference points – le flanuer, old skool sk8, interventions into architecture, the dance nature of everyday movement, etc, etc, etc. Certainly, Gladwell wasn’t making reference to Pounds shady past, it’s just that Gladwell’s work is so open to interpretation it’s just as reasonable to conceive that the artist is making an anti-fascist statement as he might be saying something about something else.

It is a rare feeling to be in agreement with Sebastian Smee. Artspace should be congratulated for mounting the show, and doubly so for what is the handsomest installation we’ve ever seen there. The place sparkles with video screens, iPods and Playstation PSPs mounted to the wall, multiple bodies moving, mirror images and endless repeats. The galleries hum with the low tones of immaculate electronic soundtracks. Suddenly, all those clichés of video art that Gladwell has made his own make sense. Individually or in group shows, Gladwell’s work doesn’t really shine. But collected together the work is genuinely arresting. More importantly, however, it doesn’t matter what any of it means. It doesn’t matter what anyone says about the work. It doesn’t matter if the subcultural signifiers are as relevant as winkle pickers. What matters is that it is. And that’s all anyone should care about.