Din Heagney heads down a crumbling alleyway somewhere in Melbourne to find Until Never, a place where graf meets ochre…

Until Never has long been the bastion of street and outsider art in Melbourne. For those who haven’t been there, the gallery is archetypal of this town: down a crumbly alleyway, up an old flight of stairs, hidden from view and protecting small treasures that would otherwise be swept away in a tide of polished trend. I often wonder at how economic constraint has become a defining feature of our cultural survival and how it now informs presentation.

Until Never made its name by treating seriously the kinds of work the establishment once passed over. Some of the first major graffiti exhibitions were held here. Those artists who are now featured in national collections and major commercial galleries started out as little punks with spray cans who learned under the careful eye of founder Andrew Mac.

For more than a decade, Mac has defended his turf, the Citylights Project light boxes and the graf-covered walls of Hosier Lane, against the tidal policies of local councils and state government departments, who still can’t agree amongst themselves whether they love it or loathe it. These days, the laneways around Until Never are one of the most photographed and visited places in the city. Whenever Mac thinks the laneway walls have become tired or over-tagged, he repaints them and invites some artists down to start all over again.

Essentially, Mac has been ‘keeping it real’ in a compelling environment where slick galleries now snaffle up the street artists who first started out in these alleys. While there’s nothing much outsider about street art these days, the techniques have remain largely unchanged – in fact they have remained unchanged for thousands of years.

Back in 2004, Mac and I presented papers to a national print conference about the connections between Indigenous Australian arts practice and contemporary stencil art. We discussed disenfranchised youth and disenfranchised cultures and the ways these art forms can be used to symbolise place, imbuing meaning beyond surface, and creating a community and connecting people through mark making.

It was this same kind of thinking and conversation that has been taking place at Baluk Arts, a new Aboriginal arts collective on the Mornington Peninsula, an hour south of Melbourne. Baluk, a local Boonwurrung word meaning clan or extended family group, develops a range of programs for more than 1000 local Indigenous people, with the artists in the group ranging from 12 to 62 years old.

“Baluk Arts approached me, having already considered the interesting and apparently previously unexplored link between ancient traditions of rock art and stenciling, and contemporary forms of stenciling,” Mac explains, “I jumped at it. The first workshops we did early last year focused on collaboration and aerosol, with the workshops this year moving on to explore the use of ochre.”

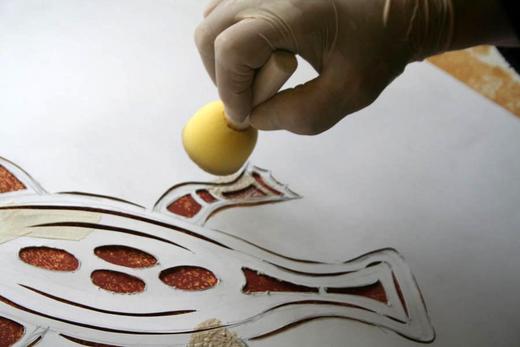

Working with Mac and a guest mentor, Regan Tamanui (HaHa), the artists explored stenciling practices, which were then combined with traditional mapping and markings for community and place. The Baluk artists mostly worked in studio but the group also visited Gariwerd (The Grampians) in western Victoria to study some of the oldest surviving rock art in southeast Australia. There are significant collections of rock art sites throughout the national park, including: Billimina (Glenisla shelter), Jananginj Njani (Camp of the Emu’s Foot), Manja (Cave of Hands), Larngibunja (Cave of Fishes), Ngamadjidj (Cave of Ghosts) and Gulgurn Manja (Flat Rock).

While visiting the district, the Baluk artists also collected various ochres to make into paint, eventually creating a suite of colours that became a shared palate for the entire show. The resulting works morph between modern representation and earthy symbolism. Sand, ochre and spray paint blend across these works on paper, depicting famous sportsmen like Nicky Winmar and Lionel Rose to traditional ancestor spirits and through to fresh bubble-ups like Chaigen Watson’s standout Gunditjamara, a three tone series combining graf style with traditional ochre.

As one patron at the gallery commented: ‘Aboriginal art is fine when it maintains its traditional appearances, it’s when it becomes urban and relates to real issues affecting Aboriginal people that it becomes uncomfortable for the establishment.’ I won’t go into the arguments that ensued after that comment. Suffice it to say that Biik is a show that successfully engages traditional practices with contemporary methods in a very real and unaffected way.

Biik Land – Ochre stencil prints by Baluk Arts

Showing until 6 November 2010

Until Never

2nd Floor 3-5 Hosier Lane, Melbourne Vic 3000

Open Wednesday–Saturday, 11am-5pm

+61 (3) 9663 0442

Featuring: Mariah Briggs, Jan Chapman Davis, Donella Gadsby, Boyd McLean, Jemelya Gadsby, Rhoda Green, Korrinne Hudson, Peta Hudson, Bob Kelly, Dan Kelly, Jacinta Kelly, Maggie Kelly, Nola Lauch, Patrice Mahoney, Tracy Roach, Doug Smith, Chaigen Watson, Ada Weston.

Baluk Arts

http://balukarts.org.au

Brambuk National Park and Cultural Centre (Gariwerd)

http://www.brambuk.com.au/