John Kelly surveys the wash up of the Australia exhibition and finds, contrary to critical and popular opinion, the show is an unfortunately accurate history of Australian art...

“An author’s first duty is to let down his country.”

Brendan Behan, Irish writer 1923-1964

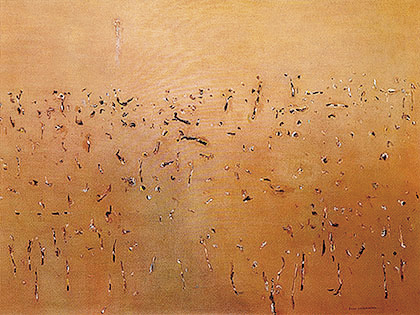

In 1968 Fred Williams painted ‘Yellow Landscape’. To some it might look like a minimal abstract composition however you might also read it as a field, or in the Australian vernacular, a paddock or even a bit of scrub. This brings an element of humour to the work for back then, the word field, had multiple meanings. Williams, well aware of this, painted his field sparsely, minimally, using gestural marks, on a thin expanse of oil paint.

In 1968 ‘The Field’ also referenced an exhibition of abstract paintings held at the NGV. Although he literally painted them, Fred Williams was not in The Field but then the artists in that show, like John Peart, did not reference the local landscape, they referenced the supposedly far more ‘sophisticated’ minimal colour-field theory espoused by American art critic Clement Greenberg. Looking back we can see the zeitgeist of minimalism course through Williams canvases however in all likelihood he was considered far too parochial and insular for The Field. After all it was as much about positioning the new NGV as modern, international and therefore sophisticated, it had little to do with Australian art.

However times change and conversely all bar one of the artists who were in The Field are not in Australia, the major Autumnal exhibition at the Royal Academy in London. Artists like Peart who dominated the late 60’s winning four of the more important prizes have been erased from this ‘art history’. One reason may be that Australia aims to evoke a sense of place through the distinctiveness of the Australian landscape, hence Williams’s fields are in and the artists who were slavish to Greenberg’s colour-fields are out. I can’t help but think of Rowan Atkinson devilish character ‘Toby’, in a comedy sketch where he brings order to eternal damnation and tells the atheists “…you must be feeling a right bunch of nitwits. Nevermind.”

Fred Williams, Yellow Landscape, 1968-69. Oil on canvas, 139x193cms.

However Toby may have also been the Royal Academy’s inspiration for this large display of Australian art, which is arranged not unlike Atkinson’s hell. For obvious reasons the French and Germans are not included but the colonial British are over here, Aboriginals are over there, white Australian modernists are in that room and those of you who paint on bark please go into that small side room! Contemporary artists stand alongside Toby’s “sodomites” up against the wall for there is no sculpture in ‘Australia’ unless you think a couple of emu eggs and a furry installation just about sum it up. The Field painters must be in heaven.

In the first major room of the exhibition Aboriginal paintings from the past forty years are shown together. One London critic Adrian Searle describing them thus; “While extremely beautiful, they are also extremely difficult to read. To what degree should we see them as a kind of art…” I think of him saying this in a Basil Fawlty voice for it seems odd that an experienced art critic who has been dealing with the eclectic range of YBA’s in a post-modernist environment, where anything can be art, suddenly has a brain fade when confronted by western desert painting. Does all art have to be read similarly to that which is made under fluorescent lights in the east end? Can the work made under the southern stars not simply be experienced as a wonderful exuberant display of creativity and painterly expression? Why not simply engage with it as a form of human expression that we commonly call art? The more pertinent question Searle might have asked is why does the structure of this exhibition and his response have all the feel and sensitivity of a 1950s Alabama bus. Even if the aboriginal artists are being asked to sit at the front it is still an unnecessary form of segregation. The Royal Academy’s curatorial apartheid mimics many Australian institutions that also still segregate aboriginal art into ‘special’ areas, which for the AGNSW for many years was in the basement and at the NGV its aboriginal collection is literally a few blocks away from its main building that holds its prized European art collection. By segregating aboriginal art into a separate space there is an inference that is not all that hard to read! In fact Searle kind of puts it in black and white. Having ditched the White Australia policy and the colour field theory, it is now time to let go of the segregated old bus as well.

The story of Australian art would be better served if it were simply shown in the chronological order it was created in, so that in 1788 Captain Cook cometh along and this thing called art follows. The contemporary rejuvenation of aboriginal creativity kicks off in the 1970s when the modern missionaries give them some acrylic paints to play with. Seeing their incredible creations alongside and in relation to their contemporaries in Williams and Brett Whitely would be something quite special. The strength of artists like Emily and other aboriginal woman artists would also go some way to providing a gender balance to Australian art which in the 60s and 70s is akin to an Australian pub during the 6 o’clock swill i.e: all men.

We come across another curious type of discrimination in Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly series, which are represented by only four panels. Having recently seen the complete set in Dublin it is hard to imagine why any curator or institution would accept the culling of this magnificent series of works that might be considered a singular piece. The series forms the fulcrum for 20th century Australian art. They capture not only the spirit of Australia at the mid point of last century but also convey the relationship we as a people have to our British history and its empire at a point in time when that relationship changed forever. This was due to the war and the fall of Singapore, which ushered in the arrival of the Americans. It is important to remember the Australian passport only came into being a year or two after these works were painted.

Nolan’s genius was to let Australia down – he deserted the army and then elevated the son of an Irish convict and cop killer to hero status, telling Kelly’s story like none before. The paintings also reference the many cultural wars that raged around Nolan (including the Ern Malley and William Dobell trials) as well as the historical and military ones that engulfed the world, all set within the post-apocalyptic landscape that we knew was out there but rarely ventured into. He showed and celebrated the fact we were literally the outsiders to that vast inland sea.

Nolan stands alone in our history as the major figure of the mid-twentieth century yet his presence here has been officially diluted and so has this telling of Australian art history. Despite this, his four modest three foot by four Masonite panels dwarf his contemporaries and the larger and newer more technological works that reference him.

Crossing the threshold into the contemporary we find a mirror to the current Australian ‘art-world’, which is defined by the institutional – commercial gallery axis much as Greenberg’s colour field theory held sway in 1968. Maybe unfairly you could play the game of spotting the next Peart amongst the contemporary prize-winners. The many relationships between the institutions, galleries, their trustees/boards, benefactors and personalities are obvious upon the walls. Peter Booth, a master of the big figurative landscape and who was in The Field, is strangely represented by a singular small work on paper hung amongst some photography begging the question; whom has he upset recently? But at least he is there. There are some seriously good artists that have been left at an unknown stop quietly waiting for a bus to arrive. None more so than the sculptors, who judging by their absence would seemingly not have engaged with the Australian landscape in the past 200 years. The press release stated that Judy Watson had been commissioned to make a sculpture for the RA courtyard, but if she did it was an invisible one. Maybe she let them down? Rosalie Gascoigne’s sculpture ‘The Inland Sea’ in the NGV would have been extremely pertinent piece for this exhibition.

Not surprisingly the London critics have savaged the show and one feels that it might still be 1968 in Australia, where the institutions that control and give direction to our culture are still battling their own crisis of identity, to such a degree, one critic in London suggested; “You can partly blame the Australians themselves for the lack of appreciation. More than most countries, it has carried a baggage of hyper-sensitivity about its place in the world…” Another described it dismissively as the “official history”. But then ‘Australia’ is such an accurate reflection of Australia today it might be an important marker. One that lets contemporary Australian artists know that to board the ‘Team Australia’ bus is not necessarily a good long term career move. As Nolan, Williams and the Western Desert painters have shown, at times it can be incredibly important to be outside the official version even to the point of letting your country down, however Australia should not be letting its artists down. Sadly it has.

Postscript: After finishing this essay I enquired after John Peart through a colleague and was informed he had tragically died the week before. Vale John Peart.

Thanks for the best review on ‘Australia’.

Hear hear…penetrating, even-handed review…despite not having seen the show, one gets the point.

My earliest memoriesy of contemporary art in Oz was of a Prom concert at the Sydney Town Hall where John Peart painted an extremely large exuberant canvas to music by Nigel Butterley. Just a girl still in boarding school, the entire performance was a revelation to me, the most exciting thing I had seen or heard since the Beatles…

Vale John Peart.

A very insightful article! I saw the show. It was safe, predictable and (unforgivably) boring. It was definitely not an accurate indication of Australian art, past or present. It was as though the curators had sat around and thought, “What is the blandest, most predictable exhibition we can put together?”

Unfortunately, Australia is currently in the grip of such bourgeois, bland, insular curators, who really do think that they are somehow forging the culture, when, in fact, they represent its slow, agonising death.

I walked around the exhibition thinking, “Where is the edgy work? Where is the politically-incorrect work? Where is the subversive work? etc etc etc”

Instead we got Predictable. Instead, we got The Known. Instead, we got Grey.

Australia and its artists deserve much better than the boring exhibition these bureaucrats cobbled together while skimming through their Art & Australia magazines.