Luise Guest takes a look at Snake Snake Snake at Sydney Town Hall: an exhibition in celebration of Asian Australian artists…

The Snake is the sixth sign of the Chinese Zodiac, and apparently it is the most enigmatic, intuitive, introspective, and refined of the animal signs. People born in the year of the snake are supposedly insightful and naturally intuitive, with an appreciation of beauty. It is possible that as someone born in a ‘monkey’ year I am just a little jealous. To complicate this zodiac business further, 2013 is a ‘Water Snake’ year, and the characteristics associated with this part of the lunar cycle are insight, determination, persistence and motivation, as well as a certain degree of mystery. All of this connects rather nicely with the exhibition of works by Asian Australian artists marking the start of the Lunar New Year celebrations at Sydney Town Hall, ‘Snake Snake Snake’. Curated by Catherine Croll of Cultural Partnerships Australia the exhibition brings together works by 45 Asian Australian artists with Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai, Korean, Indonesian and Indigenous heritage. They range from well-known figures such as Vernon Ah Kee, Laurens Tan and Lindy Lee to emerging artists, and they have been drawn from all over Australia.

Gregory Leong Kwok Keung, China Dolls, from the Asian Century series, Digital Print on Archival Paper mounted on Aluminium, 84 x 60, image courtesy of the artist.

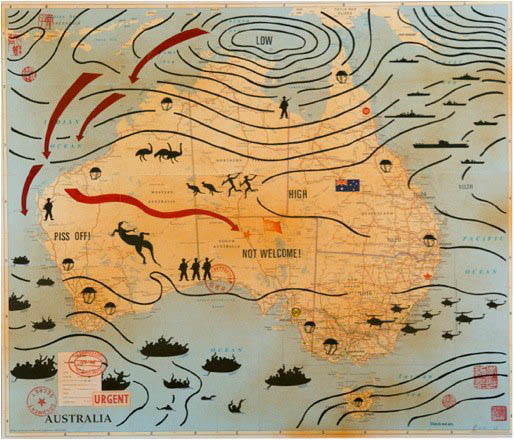

Difficult personal journeys; hybrid identities; current attitudes to refugees: all these are present in a diverse and eclectic range of works. Particularly poignant are two small works by Guan Wei. ‘Fragments of History No. 6’ is shaped like a miniature continent which has been somehow set adrift, and features his characteristic motifs of lyrical floating clouds, map coordinates, and meteorological patterns, with the silhouette of an elegant Enlightenment figure (coloniser? conqueror? pirate?) surveying tiny fighting humans. Catastrophic violence is suggested in Guan Wei’s refined works, but it appears to be happening at a great distance, and is observed with detachment, obliquely. ‘Trepidation Continent No. 2’ is as close as this artist comes to overtly expressed anger. A map of Australia reads ‘Piss Off’ and ‘Not Welcome’. The interior of the continent is largely unpeopled, apart from a row of emus, some kangaroos being hunted by Aboriginal figures, and a large goanna. Soldiers with rifles patrol the perimeter and helicopters and naval gunships guard the coastline. Boats filled with tiny beseeching silhouetted figures are sent out to sea. Some are drowning. In the corner of the work, an official looking stamp reads ‘Top Secret’. The artist, who came to Australia in 1989 when our government’s policy towards those seeking asylum was a little different, is observing current realities. The image is menacing, reflecting contemporary discourses of suspicion, paranoia and hostility.

Guan Wei, Trepidation Continent No 2, Drawing on Paper, 80 x 70, image reproduced courtesy of the artist.

Other works reveal narratives about belonging and identity. Tianli Zu works with the tradition of paper-cutting, which she reinvents and extends, often using video. In her work for this show, ‘Nuwa is Pregnant II’ she explores the concepts of yin and yang, masculine and feminine. Two large panels stained with Chinese tea and ink hang from the ceiling, intricately cut and casting elaborate, ethereal shadows. The shadow is a metaphor for all those things which are repressed or hidden in the real world, including femininity, desire and death. The act of cutting the paper is both performative and cathartic, creating something new and at the same time slicing away at that which is negative. Like so many other artists of Chinese background, the traditions of scholarly painting and of folk arts such as paper-cutting have provided a rich source of imagery and of symbolism.

Similarly, Lindy Lee in her work ‘Simple Hearted Flowers’ reflects on that which is tangible and visible – the physical world – contrasted with an evanescent shadow realm of shifting realities. Speaking about her work at the Museum of Contemporary Art last year, Lee revealed that as a young woman she herself had always felt shadowy, like a “bad copy”, alien in both Chinese and western contexts. Her experience as “the only Chinese girl in school” was the key to developing her own practice, which is now steeped in the traditions of Buddhist thought. After many years of appropriating canonical western works through techniques of photocopying, printmaking and painting, in an extended investigation of what it means to be an outsider in the “2nd degree culture” of Australia, Lee turned her eyes towards China. “The materiality [of my work] had to hold the essence of what I was trying to do,” she says, and from that point references to the five Chinese elements of wood, earth, fire, metal and water has underpinned her practice. “Everything that is has a shadow” she says. It is not possible to separate dark from light, or the material from the immaterial. The reflective black steel in this work, with holes burned into its surface and subtle traceries of Chinese imagery, suggests the enduring strength of an ancient culture as well as the ephemeral nature of our human existence.

Tianli Zu, Nuwa is Pregnant II, 100% cotton paper, Chinese tea, ink, hand cut 420 x 120 each panel, image reproduced courtesy of the artist.

Muzi Li’s ‘Gates No. 1’ is based on a diary of demolition initiated when she returned to Beijng and discovered the extent of destruction wrought by urban renewal projects. Dislocation and distress at the loss of familiar architecture resulted in a series of layered photographs in which images merge to create a sense of an imaginary place, a ‘no-man’s land’. Pei Pei He’s intricate and delicate ‘City Scroll’ drawing reflects her careful observation of the world of the street and the crowded urban landscape. It is almost like musical notation. Min Wong’s series of photographs on aluminium, ‘Asian Century’, explores the trace elements of the White Australia Policy which underlie contemporary discourses. When we glimpse ourselves in the reflective surface of the aluminium in ‘Asian Century‘ or peer into the Vinyl surface of ‘Hungry Ghost’ we are forced to consider how we may be implicated in the racism that still exists in Australia, both overt and covert.

Three works by Hu Ming, trained in the traditions of extreme realism in the ‘gong bi’ style of painting, parody ancient worlds and communicate the concerns and anxieties of today. ‘Nuclear Karma’ depicts an idealised goddess figure, with lotus flower and fan, the mushroom cloud beside her an echo of the twisting clouds of traditional scholar painting. The artist’s personal story is intriguing. During the Cultural Revolution she joined the People’s Liberation Army and worked as a nurse in a military hospital. Her paintings which at times are a strange blend of pop kitsch imagery and propaganda poster are intended to convey the strength of women as well as a range of current political references. Similarly satirical, Gregory Leong Kwok Keung’s ‘The Asian Century Series’ presents tableaux reminiscent of absurdist Pop collages. Julia Gillard is represented as the Lotus Fairy in thrall to Kuan Yin the Goddess of Mercy in a work entitled ‘China Dolls’. In another work she is taking tea in a group that includes a sexy looking Margaret Thatcher (unlikely though that sounds), Queen Victoria, and the Dowager Empress Cixi. The meaning is a little obscure but the parodic intention is clear.

Hu Ming, The Deep Red Lantern, Oil on Canvas, 120 x 90, image reproduced courtesy of the artist.

Some video and photographic documentation works include Jason Wing’s ‘Great Wall Project’, constructed when the artist was undertaking a residency in Beijing through Redgate Gallery. He found a wall made of bricks in the demolition zone that makes up so many Chinese villages, and decided to paint the Aboriginal flag on it, in recognition of his mixed Chinese and Aboriginal heritage. The next day he found the wall gone – the bricks used in a building project. The disassembled wall, he told the China Daily, is a metaphor of what has happened to traditional culture, both in China and in Australia.

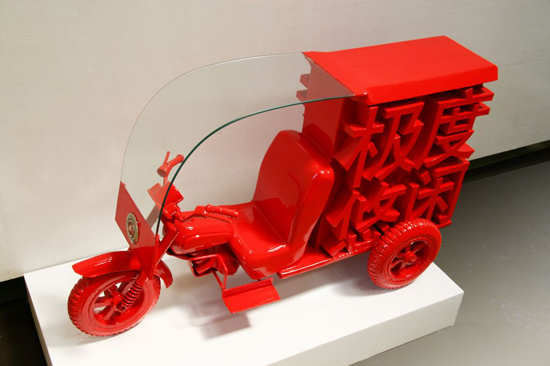

Laurens Tan, Beng Beng Standard, Fibreglass, Steel, Plastic, Baked Enamel, 98 x 56 x 40. Image reproduced courtesy of the artist.

Laurens Tan, a sculptor whose work is informed by architecture, graphics, film and industrial design, is represented here with Beng Beng Standard, one of a series of tricycle-like structures bearing upon them Chinese characters. He has long had an interest in language and meaning, an interest developing in part out of his experience of being both foreign and Chinese in China. Born in the Netherlands to Chinese Indonesian parents, growing up in Australia and then moving to Beijing as an established artist, his experience of the constant frustrations and difficulties of communication have informed his work. In recent years the ubiquitous Chinese tricycle, seen everywhere in Chinese cities carrying huge loads of firewood, recycling, construction materials, occasionally people, and pretty much anything else you can imagine, has been a recurring motif. In Tan’s work they are the bearers of messages in Chinese characters – so your experience of the work will be quite different depending whether or not you can read Chinese. This version is bright red and shiny like a desirable toy, suggesting the transformation of China into the land of massive (and very conspicuous) consumption.

Darren Xianhe Kong, Men In Disguise 2, Digital Metallic Print, 76 x 102, image reproduced courtesy of the artist.

Other engaging works include Darren Kong’s rather pudgy and unheroic male figures appearing rather sheepish under their Chinese Opera face paint, and a lyrical calligraphic abstraction from Graeme Kuo, whose work I reviewed in the ‘From Scrolls to Zines’ show at Janet Clayton Fine Art.

Ideas about communication in all its forms underpin the works in ‘Snake Snake Snake’ – as does the sense of a rich hybridity in the Australian identity that is absolutely to be celebrated.

The exhibition continues until February 23.

Damn those red lantern girls are hot!