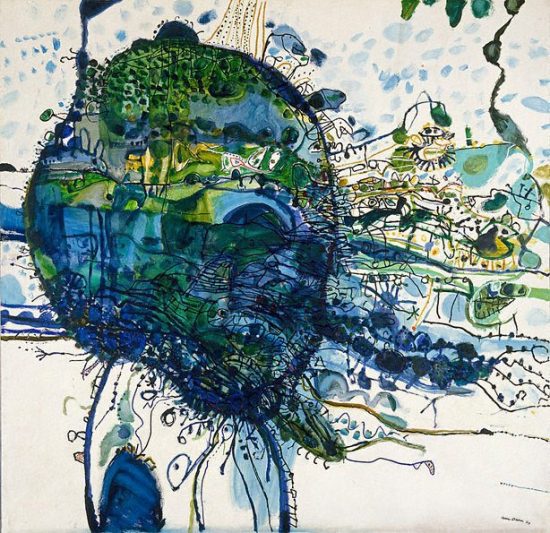

John Olsen, Five Bells, 1963. Oil on hardboard, 264.5 x 274.0 cm

The saying goes that the only difference between a radical and a conservative is 10 years. For John Olsen, the 65 years of his exhibiting career charts the journey from young radical to the beret-topped bohemian par excellence of Australia’s contemporary art establishment. As the avid student of John Passmore and Godfrey Miller, and an early acolyte of Marc Chagall – with a touch of Pablo Picasso – Olsen is literally the last man standing of that grand generation of Australian artists who created modern painting from the ground up: the men and women who quit the country to tour Europe and return home later with big ideas and matching ambition.

The opening of John Olsen: The You Beaut Country at the National Gallery of Victoria in Federation Square, Melbourne, marks a major collaboration between the NGV and the Art Gallery of New South Wales – a massive career survey of 88-year-old Olsen’s work, curated by the NGV’s David Hurlston and the AGNSW’s Deborah Edwards. With a five-month stint in Melbourne, the show will then move on to Sydney to open at the AGNSW in February 2017.

It is a huge exhibition, encompassing all of Olsen’s works from his student days, through his rebellious phase in the 50s – when with a fellow art students he picketed the archly conservative Archibald prize and the AGNSW’s board of trustees – to his sojourn to London, Paris and Spain. The exhibition then follows his triumphant return in the early 1960s and his ever-proliferating output – paintings, drawings, works on paper, ceramics and tapestries – up to the point where Olsen was eventually no longer the outsider, but the grand old man of Australian art. In 2005, Olsen won the Archibald prize – a richly savoured irony.

Olsen’s early reputation rests on the paintings he produced in the early 60s – big colourful works often composed around a large circular motif skirted with line work that hovers between abstraction and figuration. Darlinghurst Cats (1962) is a fine example of this approach – a cat’s body floats like an island in the centre of the canvas. What appears to be a plant-like extrusion on the left morphs into a cat’s head and a feline body emerges below. Other works from the period, such as Entrance to the Siren City of the Rat Race (1963) and Entrance to the Seaport of Desire (1964), feature large accumulations of line and colour that appear abstract but from which sketchy images emerge: bodies, a rat, a dinosaur or a crocodile.

Olsen’s major work of the 1960s, Five Bells (1963), is deservedly considered a major Australian painting of the period. Dominating the painting is a cell-like form in which tendrils of line and colour coalesce, leading the eye back to the centre. Partly a representation of Sydney Harbour with decipherable pictorial elements – trees, houses, parks – it’s also an impressionistic, subjective selection of the artist’s imagination. This is Olsen’s signature style: a conflation of perspectives and subjective responses to places and things, from animals, seafood paella, and the deep waters of the harbour, to outback landscapes, flattened and contoured with line as if viewed from a satellite.

For artists who defiantly paint in their own style, there is a real chance that the world will eventually stop caring. We feel as if we know an artist’s output and when it stretches over many decades, as in Olsen’s case, a major survey such as this one has to try to make sense of all the repetition, obsessions and false turns. Judicious editing is the key: for a very long time after the late 1960s, Olsen produced paintings that seem to make only incremental progress in subject and style. This has much to do with the commercial market; people want an example of an artist’s work and in their signature style, and most successful artists are happy to oblige.

Olsen’s major market is his canvases, but he also does a nice line in affordable works on paper and the sheer ubiquity of his pictures of frogs nearly marked the end of his career as a serious artist. To the exhibition’s credit, the amphibian makes only a few appearances. Works that seem to stray from this painting style – such as his landscapes, which evoke the work of Fred Williams – are included, one suspects, for the sake of completeness.

Surprisingly, Olsen’s last great works are relatively recent. His paintings of Lake Eyre in the early 1990s are as significant in their magisterial view of the landscape as his early work, yet pared back and simpler in their effects. Yet Olsen has recently turned his back on the harbour to paint his favourite Spanish dishes, proving that truly great artists can do whatever they like.

I think it’s in Olsen’s book , Drawn from life, where he admits a partiality for making and eating paella. I am surprised this reviewer doesn’t recognize this has almost always been the subject of his paintings. And all power to him. It shows his unconscious emerging on the canvas, which qualifies him as an artist.

No, it hasn’t “almost always been the subject of his paintings”.- AF