The winner of the Archibald prize 2017 for portraiture has been awarded to Mitch Cairns for his portrait of artist, and partner, Agatha Gothe-Snape. A runners-up highly commended rosette goes to Jun Chen, for his portrait of retired gallerist Ray Hughes.

Mitch Cairns, Agatha Gothe-Snape. Oil on linen, 140.5 x 125 cm.

Before we get to a discussion of these works and the finalists, and a quick tour through the accompanying main prizes – the Wynne prize for landscape and figure sculpture, and the Sir John Sulman prize for subject and genre painting – let’s pause for a moment to consider a couple of simple questions: what is the state of portrait painting? And what does the Art Gallery of NSW’s storied annual prize, now in its 96th year, tell us about the kinds of choices made in its selection?

Classical portrait painting as a genre has a limited number of variations, generally being a rendition of the subject’s face, or head and shoulders, but in practice will also occasionally include a full figure, either seated or standing. The other measure of a successful portrait is that it is said to have captured a “good likeness” – a somewhat problematic claim that is often very hard to judge.

Cairns’s win, widely predicted, is for a picture that is for the most part a classical portrait, albeit one with a seated figure, rendered in the artist’s trademark style that is both Modernist in influence – Matisse, Picasso, et al – but contemporary in its graphic edge. It’s also demonstrably a good likeness. Since the painting fulfils the basic requirements of the genre, all objections to its award are merely whinges over style. With two close calls with the prize in previous years, Cairns’s win was perhaps inevitable in the same way that artist’s with equally accessible styles, say past winners Del Kathryn Barton or Adam Cullen, eventually won through sheer persistence. The portrait also occupies a sweet spot between classic, generic features of a portrait, and something a little more adventurous.

The Archibald prize is an award given by a committee – the trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), which includes two artists – that in part explains why the highly commended work, Chen’s Ray Hughes picture, couldn’t be more different to Cairns’s painting. Hughes, a veteran gallerist who is now confined to a wheelchair and ill-health after decades of good living, is shown on a dark stage behind some black curtains.

It’s worth checking out the finalists of one of the UK’s mostly hotly contested portrait prizes, the BP National Portrait Prize now showing in London, if you want to see a truly conservative selection of contemporary portraits. Most of these works display prodigious painting skills, stick to generic rules and feature fairly standard compositions, and are for most part utterly boring.

Like all genres, be they in art or literature or film, the really interesting stuff for me takes place at the margins, where the rules of the genre get bent and broken. The purists might complain, but comparatively the AGNSW’s annual Archibald selection is usually a much more lively affair than its straight-laced cousins overseas with a more daring combination of pictures that range from the tediously accomplished, to the inept and amateurish, to a thin band of finalists that could conceivably be thought to create a “good likeness” while doing something interesting with painting itself.

It’s not a bad likeness of the divisive personality, and it’s painted in the ever-popular expressionist style so beloved by the public, but the work is also suggesting that Hughes is not long for this world, a stage play about to meet its final curtain. Chen’s huge, oil-encrusted canvas was pointed out to me as a potential winner at the unveiling of the finalists a couple of weeks ago and I fell into a deep, panicked sweat worrying that such a grossly obvious picture, and one so lugubriously painted, could win. Where the trustees have often been guided by sentimentality, this time, thank god, they erred on the side of discretion.

The tension between traditional portraits and works that sit at the limits of what most people consider a portrait is the friction that fires up the whole engine of the prize. Paintings by Robert Hannaford, Phil Meacham, and Paul Newton among others are the traditionalists, portraits with classically composed and painted realist images of men in suits, painted at large scale and given pride of place on the walls. These works stand out for the fact they are completely unremarkable. The sad part is that better, more modest works by women artists such as Kate Benyon, Vanessa Stockard and Natasha Walsh’s self portraits, tend to be overlooked. These are the gems in the selection, along with other traditionalist pictures by painters including Andrew Bonneua, Keith Burt and Gerard Smith.

The other end of the spectrum is where questions get asked such as “is this a portrait at all?” Tjunkara Ken’s self portrait I am tjukurpa, my tjukurpa is me… looks like it should be in the Wynne prize – is this not a landscape? If one can conceive that country and identity are the same thing, then of course, why isn’t it a portrait? The old conceptual art fallback of saying that something is something because the artist says it is has always been good enough for me, although many people will disagree. Sophia Hewson’s Untitled (Richard Bell) is a portrait in some senses because it features an image of the Indigenous artist Richard Bell prancing across an alpine meadow in the style of Disney and the Sound of Music hand-in-hand with Hewson. This is a picture with a big idea behind it, to satirically depict white guilt and raise the question of why a person of colour has never won the Archibald. That a young white woman is asking this question prompts further debate provided for you in the space for comments below.

Some have suggested that this a poor year for the Archibald but in reality the prize only ever comes down to perhaps half a dozen paintings. Cairns deserves his win as his work genuinely belongs in that slim selection of good paintings, but there are others on my personal wish list for future wins: Vincent Namatjira’s brilliant Self-portrait on a Friday isn’t just a great painting, it’s also a classical portrait, as is my other favourite, Marc Etherington’s playful but exact portrait of fellow artist Paul Williams. Perhaps next year. As to the state of portraiture, if more by accident than design, the Archibald offers up a tasting menu of everything that’s good, bad and indifferent in the genre. There are “good likenesses” and there are bad paintings.

Betty Kuntiwa Pumani, Antara. Acrylic on linen, 200 x 300 cm

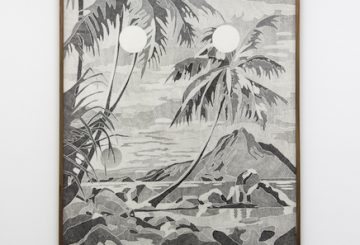

The Wynne prize was remarkable for the number of paintings by Aboriginal artists. Some have suggested that the decision by the AGNSW to hang the Indigenous paintings together in the central gallery usually reserved for the big pictures of the Archibald prize, served to artificially separate the artists from the rest of the field, and that this was a bad thing. This thought didn’t actually occur to me looking at the finalists, rather the hang seemed to make most of the rest of the Wynne field look very ordinary. Betty Kuntiwa Pawmani’s winning Antara is a magnificent painting, a swirling combination of white and red that depicts the landscape of the artist’s country in South Australia. My personal favourites in this selection-within-a-selection were Barbara Mbitjana Moore’s Rock holes near my country, Ti Tree – Anmatyerre country, and Yaritji Young’s Honey Ant Country, paintings that produce dazzling visual fields dominated by circles and gestural lines.

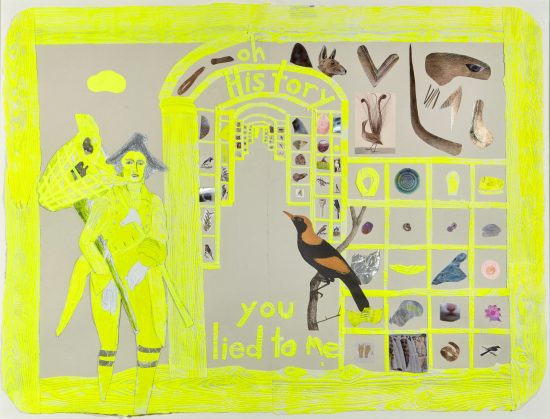

The exit to the coffee shop is through the last section of awards festivities, the Sir John Sulman prize. The category is so wide, and so ambiguous, that it’s basically an open category for contemporary painters to enter anything they please. Selected and awarded by a fellow artist, this time by Indigenous artist and Archibald-finalist Tony Albert, the award goes to Joan Ross’s Oh History, you lied to me, a work in the artist’s ongoing project, satirising colonial Australia and its contemporary manifestations in kitsch, here an amalgam of natural history museum artefacts looking rather like a nightmare, hi-vis tea towel. Of the rest of the Sulman there are some fine works by Tom Polo, Jon Cattapan, Karen Black and Michelle Cawthorn. Like the aftermath of an overstuffed awards dinner, and after all that art, I need a cup of tea and a good lie down.

This review was first published in a slightly different version by Guardian Australia, July 29, 2017.