Someone last year asked us what we thought was good art writing. We’re always mouthing off about what we think is bad but, come on, if you’re all so goddamn smart, what’s good?

Well, what we want is an art writing that’s relevant to our experience as people who love art, but which also acknowledges that there are other things in the world besides what goes in a gallery. You can probably tell from our own art writing that we like to bring in experiences and anecdotes about our lives to give some context to our reactions to the form and content of the art experience. We also value writing that is self deprecating and has an honesty to its opinions and, if it can also contain some sense of excitement and engagement with what it loves, all the better.

In April Kings ARI in Melbourne staged the group show End that included the work of Kathy Bossinakis, MutluCerkez, Charlotte Hallows, Fiona Lowry, Sharon Muir and Clare Parish. The handsome four page catalogue to that show made its way to us and we eyed it with the usual combination of envy and disdain we hold for most things that happen in Melbourne. Sitting in the Art Life office eating a sandwich, we glanced over the catalogue and unexpectedly found ourselves reading the accompanying essay with intense interest. Written by Robert Cook, an arts writer who lives in Perth, the essay was everything we liked in art writing. It smartly engaged the reader in the theme of the show, explained some cogent and relevant ideas and left the reader wanting more.

After a brief round of emails, Cook has very kindly allowed us to reproduce the catalogue essay here in its entirety. Thanks to the author and Kings ARI.

“If you leave, don’t look back, please don’t take my heart away”[1].

In December 1987 I emotionally blackmailed a girlfriend not to leave me. She had this big chance to be a nurse or student/trainee-type nurse or something. Her dream. The gig was in Queensland. I said, “sure, okay, if that’s what you want, congratulations”. I then motioned to my mother’s shape hovering near my closed door and said, “maybe we should put on a record, keep things private”. I put on Changes by Black Sabbath. It was a master-stroke. Ozzy sang “We’re going through changes, bup-ba-ba”. Tony Iommi was restrained on the axe. Plaintive keyboards dominated the song’s foreground. It was too much for my girlfriend. She cried, rocking back and forth on my bed. I cried. We hugged. She announced: “I’m staying, I can’t go, I can’t leave here, leave us.” “Well, we got the real deal right?” I replied.

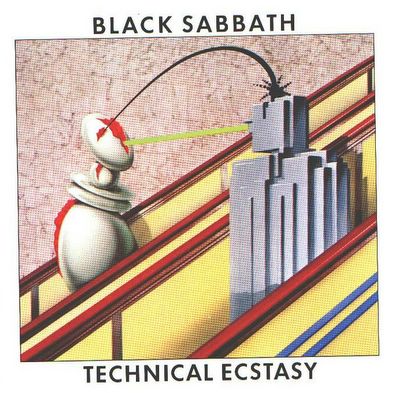

The flip-side of Technical Ecstasy [2] later we got bored and more bored and fucked and fucked and sweated and went down the beach. On the way she said she knew what I’d done. “You put on ‘Changes’ to make me too sad to go”. I said “sure”. And that decision to stay, to force things – and, worse, how we both knew it – highlighted how shit everything was between us. We were born of weakness. We hated each other, had done for six months, and should have let it all go.

But (blackmail tactfully aside) what happened in December 1987 was that we couldn’t admit a certain moment was over. It was the moment when we met at Saturday night free skating at Mirrabooka Ice Rink. It was the moment when I was funny for a change and not so gloomy. And she was whatever she was – not so uptight and dead to the world, which is mean, though true. We stayed together, after it was all over, after it was so stupid it beggared belief, out of nostalgia for the people we were at that time. People that only existed for, maybe only a matter of days, but that were so much bigger and better than we ever thought we could be.

It’s not it’s unusual. The unwillingness to let go of a moment, to leave it with a crisp manly definiteness, is central to the immature, romantic sensibility. You see it everywhere, but F. Scott Fitzgerald is the one I’m thinking about mostly now, for pretty random reasons. I’m feeling these days that my template for existence is defined by someone like Nick Carraway. As is well known, in The Great Gatsby the refusal to get over a moment is articulated via a form of doubleness. Narrator Nick looks back on what was, for him, a swirlingly social (though impersonal) golden period where he was enfolded in something bigger than himself. And his own looking back is centred around Jay Gatsby who was, himself, looking back, trying to recapture the love of his life. Everyone was trying to get something back. That’s the little novel’s tragic beauty – its retro-amplification.

For what it’s worth, it was the same in the slow burn of Tender is the Night where we witness the glimmering fade out of Dick Diver from ladies man and man-of-the-world to GP in a small, shit-hole, American town. In both – in all of Fitzgerald’s work – the inability, the unwillingness to say goodbye, to move on, is key. It’s all about keeping the moment open and active for as long as possible. Especially when it’s hopeless and damaging.

Now this is not just a personal peculiarity of me and Scottie – it’s generational. It is also imaginatively generative of a particular type of culture. See, our mums and dads worked with the legacy of minimalism and conceptualism, their hold on the “presentness” of the work, we are, by distinction, children of “the moment”. Our elders lived through the dying embers of an avant-garde that was movement after movement after movement. But somehow, for them, it was permanent. Each movement was the Final Solution, a cleansing. (Yes, I caricature them as fascistic, because, like a child, I still hate them.) And the point is that movements weren’t moments. Movements were robust and bombastic and full of screaming bullshit. Moments are fragile. Japanese. And we, as people, are more fragile because of it. When we feel that we’re in the midst of something, we know it will end and leave us bereft.

Yet it’s not just a simple awareness of the tragedy of the temporal that’s at work. No, somehow we tend to make each moment false as we extend it even when we are enjoying its apogee. We are into cultural resuscitation. Our very consciousnesses are radically historicizing. It’s part of our sensibility. And, as the cliché goes, our moments are close to seasons: the first season of The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, the third series of Buffy. Etc. As we watch, or “engage” with culture, we already see it going away, leaving us behind.

We exist like the end-tracks on movies that take over the entire substance of what went before. We’re always looking at the credits and searching for traces of what was. And we’ll stoop to anything to hang on to it. Whether we admit it or not, we all have our Black Sabbath albums, or their equivalents, at the ready. We’re always ready to play dirty and mock vulnerable to keep the moment going.

It’s why OMD’s track in Pretty in Pink felt so apt to us: “if you leave don’t look back”. They knew what they were saying. They knew its irony. That we all look back, that we cannot help it.

Not just Andrew and Molly.

So fuck, I’m not sorry old girlfriend. I’m just a symptom of a generation born to live life and make culture as if it’s all an act of resuscitation.

We are medics of nostalgia.

Flatline heroes.

Fade out.

Robert Cook

[1] Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. (1988). If you leave on The Best of OMD, A&M Records.

[2] I checked that this was the right album on Amazon. Changes isn’t listed on Technical Ecstasy, but I swear it was on my version.