At the Institute of Modern Art, a new show by Scott Redford and Michael Zavros attempts to fool the foolish – or so claims Andrew Frost.

In the blue corner weighing in at no more than 140lbs, in the Louis Vuitton trunks, Michael “Kid Gorgeous” Zavros! And in the red corner, weighing in 220lbs, wearing a vintage pair of Golden Breed boardies, Scott “The Crusher” Redford!

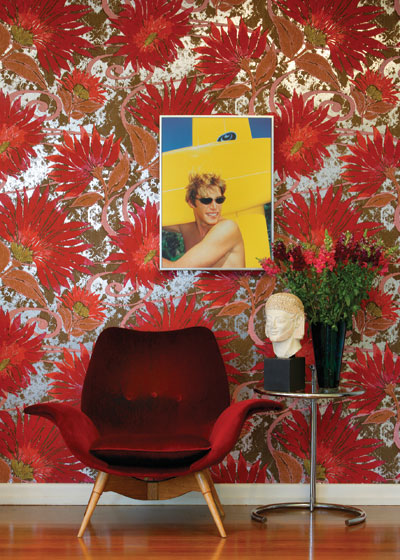

Courtesy GRANTPIRRIE, Sydney, and Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane.

These two contenders are fighting a grudge match, not against the other, but against the world – a world that does not care for surfaces and decoration. It’s a match between a super light weight vs. a cruiser weight. But before the first round bell sounds, let’s consider the careers of these two pugilists.

Zavros has had a dream run since he came up from the junior grades. They say picking your fights is just as important as winning them and Zavros’s career has been marked by a series of well-chosen bouts. His card is pretty much all wins, with a mere smattering of draws. Watching this kid fight is a humbling experience – lots of movement, a lot of style, a face so beautiful it’d be a shame to have it spoiled. He reminds this commentator of the time when, fresh out of Rumble Fish, the young Mickey Rourke gave up acting for some serious non-surgical face adjustment. Redford meanwhile is the art world’s equivalent of George Foreman, a veteran fighter who embodies that oft-quoted line of Jean-Luc Godard, vis, “a fighter only ever truly fights himself”. His card has been a series of technical knock outs, draws and bloody bouts, all of them self-inflicted, and yet he remains a serious proposition. Zavros may well rue the day he went up against Redford.

The Institute of Modern Art’s Scott Redford vs. Michael Zavros is a curious proposition. It’s a show that’s reactive, at once an unapologetic refusal to cooperate with the mainstream thinking of contemporary art making, and a somewhat disingenuous critical positioning that has been out of fashion for about twenty five years. The wall text that accompanies the exhibition makes a number of outlandish claims that are as entertaining as they are perplexing:

“Seemingly infuriated by the old avant-garde presumption that artworks should criticise and challenge their publics, their subject matter, and the art of the past, the art world is currently enjoying what Rex Butler has dubbed a ‘post-critical’ turn. Pop Life, a show which recently debuted at London’s Tate Modern, celebrates artists who aim to please and entertain, who embrace commercialism and populism, and want their audiences to like them. They include Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, Damian Hirst, and Takashi Murakami. Scott Redford vs. Michael Zavros brings this idea home, pitting two local post-critical artists—both born and bred on the Gold Coast—against one another.”

Zavros it is claimed, is an artist who makes art that is “not critical of its subjects, it is sharply self-reflexive: his ‘trophy’ paintings refer to their own status as collectibles, his ‘interiors’ are made for collectors to hang in their own homes, he exhibited paintings of handbags in a handbag store. Zavros is affirmative, never ironic or conflicted.” Redford gave up being a Queer artist who made art with a critical position on mainstream values. Now “in the twenty-first century [Redford] seemed to turn his back on criticality to celebrate the Gold Coast, its bling and teen surf culture. He embraced the language and pitch of commercialism: brands, decals, fluro-colours, and industrial production. These days he doesn’t mind people saying his works look like merchandise, in fact he proposed to turn Australia’s pavilion at Venice into a surf shop.”

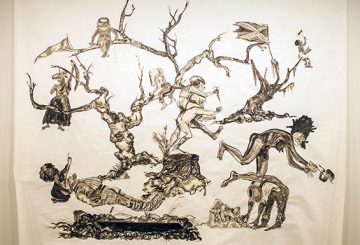

Photo: David Sandison. Courtesy Heiser Gallery, Brisbane.

It’s worth quoting the wall text at length because it’s important to decoding what this show is supposed to be about. The archness of its positioning operates at a level of obviousness perfectly in keeping with the content of the show, a clever-clever double take on the idea of surface without forsaking the very thing it claims to have ejected from the palace of mirrors: criticality. What might Redford vs. Zavros be like without the curatorial claims plastered on the wall? It’d look like a waiting room at Palazzo Versace.

The notion of criticality is at the core of what contemporary art’s function is supposed to be. By taking a critical position art making has a purpose beyond the market, beyond the compromised value system of international biennales, galleries and museums and, so long as contemporary art is meant to mean something, then those compromises can be borne by artist and audiences alike. Without this sense of higher meaning and purpose, then contemporary art – any art for that matter – is just a solipsistic rich man’s game of commodity trading. Redford and Zavros, for the most part, balance their practices on this precarious edge between meaning and decor, sometimes rather humorously highlighting this conflict.

The key image of the show – and used by the IMA in their publicity – is a Zavros picture, Echo [2009], a vaulted palace room strewn with body building equipment and weights. A small picture, Narcissus [2009] – the artist gazing at his reflection in the bonnet of a car – sits in dialogue with its opposite. At their feet on the floor is Redford’s giant chrome paper plane, Reinhardt Damm: Power Mirror [2010]. On another wall facing this arrangement is the key Redford work [made in collaboration with a designer and stylist], Gold Coast Style [2005] – a photographic still life of chrome chair, a bust, and framed picture of a surfer boy against a makeshift crucifix of surfboards, hung on a wall papered with intense gold flock wall paper. This kind of echo and reflection of each artists concern, strangely unconnected in your commentators mind until now, is blatantly apparent in this artful hang as it stretches through two rooms, one mostly Zavros, the other mostly Redford.

When Frederic Jamieson claimed that the visual in film is essentially pornographic, he described an end point of stupefied negation that left the viewer swimming in the surface of an image when the image itself refuses to betray its own object. In other words, a disingenuous negation of a criticality leads nowhere, no matter how superficially attractive the surface is. The conceptual double-bind of Redford vs. Zavros is just such an unwillingness to tackle subject through image since the images are mostly abstracted, photo-derived tromp o’leil, neither really deep nor really shallow. The enrapture of surface is a feint, a boxers hop and skip away from the battle of meaning. As much as the artist’s might try to distance themselves from irony – a particularly ‘80s kind of post modern irony at that – the surface keeps drawing us back. As Godard said elsewhere, “style is just the outside of content.”

Pretty boy aint pretty no more.

Deep Cycle Vs. Rinse and Hold

I suppose everything we do comes from a point of view, whether we have critically established that view or picked it up like getting the mumps. A bit of decoration now and then, can’t be a bad thing, but please don’t pretend that it is without meaning – one can only minimise.

I’d been waiting for this. Is post-criticality actually a thing?

its not post-citicality, its post-nihilism

Loved this show – both such great artists.