Din Heagney visits the Melbourne Art Fair, drinks champagne, gives sound art-investment advice and can’t get the wise words of Bill Henson out of his mind…

Paco Barragán commented in his book Art Fair Age: On Art Fairs as Urban Entertainment Centres that “art fairs are the domain par excellence in which the new paradigm of globalization takes place. As can no other venue, they give shape to the experience economy, which in its search for ‘spiritual consumerism’ wants to engage its clients and keep them involved.”

Barragan connects this concept of spiritual consumerism to notions of ‘good shopping’ – a type of buying that can expand consciousness, one that is less about status and more about appreciation, imagination and truth seeking. If I bought a Damien Hirst, for instance, I would perhaps call it good shopping. If I bought a Renne So or a Bill Henson, I would call it spiritual consumerism. But if I asked a group of collectors at the Melbourne Art Fair, as I did on Wednesday night, I would get a series of answers that would befuddle me until my hangover departed the next evening. One of them said he didn’t like anything, so I proceeded to ignore him. The one I knew said he only bought for investment portfolios, so spiritualism of any kind didn’t come into it. Another actually asked me what I thought he should pick up, which started other people in the little group keenly asking if I was a dealer and what I recommended and what was a ‘good buy’. I was fairly sure they were meaning a good investment, not Barragán’s type of ‘good shopping’. All of this was quite amusing as I was still on my first glass of champagne and had only taken ten steps into the Exhibition Building so was yet to see anything.

The beautiful commerce – whether good, bad or otherwise – was proudly on show at the Melbourne Art Fair, and everyone who is anyone in the Melbourne art scene was there in new threads and haircuts. After excusing myself from the odd group of collectors, I set off to immerse myself in Melbourne’s most glamorous, drunken and expensive week of art. Yet I was being bugged by all this thinking about truth and consciousness that had begun on Monday night at Bill Henson’s inspiring opening lecture for the Art Fair at Federation Square.

Amongst the vast realm of ideas that Henson covered in his poetic lecture was his concept of ‘millennial slippage’ — and idea that truth is experienced through great art, the continuum of civilisation through the ages, the places that can only be visited through art. By example, he linked his recent thinking around one of his works about the stepped Pyramid of Zozer with the beauty of a single gesture by a woman on an escalator in a suburban shopping centre. Henson happily admitted to appearing like many artists as a holy fool or even a devil in the pursuit of truth, but from this rather strange introduction, he took us on a wonderful tour – a personal art history lesson that had little to do with his infamous images and a lot to do with truth.

This notion of ‘becoming one with the artistic expression of the past’ is neatly summarised by his concept of millennial slippage, that spark in the imagination that often becomes intangible and fails when it reaches the tongue but can be freed through the making of art, potentially becoming part of the vast canon of art’s past, and so its future. Henson described this truth in art as that opportunity for transformation through work that contains ‘a sense of risk, of licence, of teetering on a tightrope, both formally and in terms of what is represented.’

Henson thankfully made no apology for his controversial work. In fact, he barely discussed it, instead presenting a commanding argument for improvements in political leadership and classical education. He defended the freedom of art more broadly, criticising both the former PM and the Minister for Arts for weighing into the attack against art. He used these as prime examples of the need for a more culturally informed leadership, one that would use ‘politics to make the world safe for art’. It is disturbingly ironic that the type of censorious prohibition demanded by so-called traditionalists would in fact deny thousands of years of human civilisation passed down through time. He made the point well, even if things became a little messier in the Q&A at the end, with the disappointingly predictable questions around the 2008 controversy – enough to feed the media so they could drag the old story out again for another run around the block. But that was only to be expected.

It’s the implications of these sort of weighted discussions that leads me to ask why these questioners seem so obsessed with misdirected thoughts of perversity in the face of truth in art. Most of the questioners on the night, and the subsequent media stories, were keen to dissect his illuminating lecture for tidbits about the former controversy — that overloaded debate on child protection and so-called pornography that led to political posturing and reductive policies that were enforced through bodies like the Australia Council, who traditionally fall on the other side of these issues. In essence, Henson was demanding much more for our children than rules and notions around consent and protection. He demanded that classical education be made available to all regardless of class and that the prevalence of ‘cultural popcorn’ churned out by infotainment media is a far greater crime against our youth than a mere photograph of a teenager.

While Henson was openly self-effacing in the light of the great artists who inspire him, the likes of Bernini, Friedrich and Titian, he was keen to point out that the apparent superhuman qualities of art that contains the revelation of truth, have often give rise to backlashes emerging from the society of the day. There is a well-worn history of using artists as scapegoats with accusations of supernaturalism, demon possession and worse as Henson can attest. More apposite perhaps were his comparisons to artists once hounded for their apparent insolence: Ovid who ended up in exile for being thought a magician, or Liszt who was accused of practicing black arts with his music, or Wilde who ended up in gaol for his homosexuality. Henson cited many enlightening examples of musicians, painters and poets who were elevated from pariahs to masters, vindicated by posterity for the greater good of civilisation.

“Criticism in the end can only be testimonial,” Henson said, “it can point to a thousand features in a work of art, it can analyse the circumstances of its composition and make every kind of illuminating contextual comparison, but in the end, in the decisive matter of judgment, you can only say wow… in order be civilised, human beings need to be able to experience art”. At that point I was ready to leap to my feet with a ‘bravo’ but there was a great silence and nodding in the auditorium, as the crowd of more than 700 considered all that he was saying. And there was much more to Henson’s lecture. It was refreshing in that it revealed more about the mind of one of Australia’s greatest living artists, than some kind of belated backlash against a bunch of expurgatory puritans who barely warrant a response.

With all these ideas swimming in my mind, I headed off to Wednesday’s Art Fair Vernissage at the Exhibition Building. I was full of Hensonian romanticism, but I have to admit I was a little disappointed at the rather safe atmosphere of this year’s fair. For starters, attendance seemed down on previous years, but that may have something to do with the $175 ticket price, or simply that it was a miserably cold and wet night out. Nevertheless, this is one of the very few opportunities for poverty-line writers to rub shoulder pads with famous artists and millionaires, and for the playing field to be leveled out by everyone drinking the same sparkling wine and being very polite.

But this feeling of playing it safe wouldn’t escape me. Everyone was so nice. And so was all the work. I wondered if there was simply too much art in the building for me to find any ‘wow’ factor at work. Or perhaps I have grown averse to niceties after spending too many years working with highly controversial artists and dangerous art. I also wondered if it was unfair to expect to be wowed at a fair, but isn’t that the point? It probably has less to do with the Melbourne Art Fair format and more to do with the artists being selected by the exhibiting galleries. While the Fair is an excellent opportunity to scan the swathe of local talent, there was distinctly less representation from international galleries this year. It’s clear that the financial crisis is still making its effects felt in other parts of the world. Conversely, Australian galleries were out in strength with many taking larger stalls, and some selecting a single artist to win over the eager eyes of the 3000 people who made up the well-quaffed crowd.

Jon Campbell’s Stacks On commission helped define the commercial focus of the Fair with an unpretentious humour, giving the central space around the bar a suburban shopping strip feel with the buzz of being in the middle of a market, where Franco Cozzo borders with bogan chic and statements celebrate everyday Australianness. In fact, there was something of an abundance of text-based works as paintings and sculptures – what I started calling ‘scupltings’ and ‘paintures’ – those po-mo blends of traditional mediums that border on art parody and nearly always leave me yawning. I would suggest that a single profanity in acrylic does not make great art, people.

While there were a few works that presented with self-conscious irony and even a couple with outright cynical anti-aesthetica, it was surprising to see so much art that we’ve seen before. It says more perhaps about the buyers market (that they aren’t buying enough if we’re seeing it again) but really this all says more about my own taste in art than in the buyers in attendance. If good shopping can elevate the consciousness as Barragán says and great art can elevate the truth as Henson attests, then dare I call much of what I saw ‘bad art’? No, I won’t jump to harsh conclusions without another visit or two first…

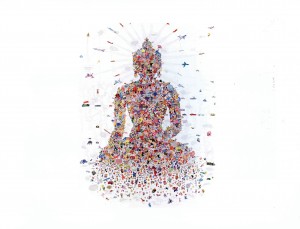

Having been uplifted by Henson’s romantic foray into civilisations and artists past, I perhaps went to the Vernissage with my expectations set too high. Overall, there was little of shock value (unless you count Adam Cullen’s satanic sex scenes), and that wow factor that Henson admitted to earlier in the week was begging for attention and so I set my sights instead on what was new to me. What I did find was more work from artists I had only glimpsed briefly in the past and so having series of works on display from the likes of Danie Mellor (Michael Reid) and Gonkar Gyatso (China Art Projects), Kill Pixie (Edwina Corlette Gallery) and Anna Eggert (Stella Downer Fine Art), Peter Madden (Ryan Renshaw Gallery) and Megan Jenkinson (Stills Gallery). Seeing new work from these artists was something of a treat, so you can expect to hear more on these artists soon.

By the time we lumbered into the after party hours later, I was still being haunted by one of Henson’s most memorable comments from the start of the week: “We go to our graves defining ourselves by the art that we know.” So I guess there’s still time to search for the truth in both the spiritual and the secular, but an art fair while a grand event is no replacement for the quiet enjoyment of a work on one’s own, where you can really get to know the art and yourself a little better.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Millennial Slippage | The Art Life -- Topsy.com

wake up Mr Heagney, you’ve been suckered by Henson’s PR machine! You seriously don’t think henson wrote that stuff all by himself do you?

@redned: Well I took notes so I don’t think I was asleep… Most of his talk was about his own responses to various artworks, his favourite artists, and some over arching philosophies, so I am fairly sure they are his personal responses. But, who is to know whether he wrote it all himself. You could say the same things about everyone in art/entertainment/politics/media/publishing/education/business, etc. If you suggest that we don’t listen to anything pre-prepared or worked on by other people then very little would pass your filter.

spiritual shopping?

kinda makes me a bit pissed off that buyers still want an investment rather than purchase a work that reacts personnally to them. guess not all are like that.

hype sells art

not heart

bit tragic. having a bad day now. bugger.

Surely the commodification of art is an inescapable ‘millennial’ reality! The art market was one of the last commercial bastions to survive the global downturn due to its unique capacity for bullshit. The Melbourne Art Fair is no different from all art fairs – full of crap (i.e. bad art) because Hyacinth & Eric love kitsch yet depend absolutely on investment advice due to niggling doubts that their naive, sentimental knee-jerk responses to art will quite cut the mustard: kitsch, like cars, rarely appreciates in value (“I don’t t know much about art, but I know what I like”, etc) and naturally it’s all about a quick return these days, with superfunds going down the toilet and tax rules re art investments about to be revamped federally.

Thus gallerists and fairs proliferate, critics lose impartiality and become de facto agents, and buyers and values are manipulated…

“Millennial slippage”, what a ‘GruenTransfer’-style corker! Mr Casby’s opener (so barking tedious – Slow TV – he must have written it himself!) was probably orchestrated by his spin doktor Sue Cato (Cato Counsel, whose clients include the Cross City Tunnel, Roslyn Oxley, Gunns, Mark McInnes, etc, (http://www.abc.net.au/mediawatch/transcripts/s1483777.htm), ), who has earned her fees for the past 2 years getting Mr Casby’s reserved car park at the AGNSW returned to him….

No need for the notebook when there’s a bigger picture to focus on.

i want a like button for uncle chas!