Luise Guest visits White Rabbit and discovers how guest curator Edmund Capon has arranged the collection…

Wang Zhiyuan ‘Object of Desire’, 2008, fibreglass, lights, sound, 363 x 355 x 70 cm image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery

In Mao Zedong’s famous exhortation to the Red Army at the 1942 Yenan Forum on Art and Literature, he emphasised the close relationship between art and revolution, stressing that art must ‘serve the masses’. He probably wasn’t envisaging a gigantic pair of gaudy pink knickers made of fibreglass and car duco; a three-headed conjoined baby skeleton in a scientific bell jar; vegetables growing in an illicit Shanghai garden engaged in a sexually explicit conversation courtesy of Chen Hangfeng’s video installation; or a baby stroller customised with spikes on the wheels, symbolising the fierce struggle for success that characterises parenthood in today’s China. Imagine the bewilderment of Mao and his revolutionary comrades in an encounter with these works and others in the new exhibition at White Rabbit Gallery. ‘Serve the People’ has been curated by former director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Edmund Capon, from Judith Neilson’s impressive collection of contemporary Chinese art.

The notion of how art might “serve the people” has an entirely different resonance in today’s China. Artists born before Mao’s death in 1976 cannot help but look back and attempt to reconcile their life experience with the strangeness of the present day. The dislocations of social transformation, globalisation, demolition and urbanisation which have swept away the revolutionary past, ushering in a world filled with uncertainty, have rendered many of the tropes of the first 1990s wave of contemporary Chinese art passé. A new visual language is emerging, with which artists can respond to the strangeness of their contemporary world, in which enormous disparities of wealth, education and personal freedom are creating new schisms in the social fabric. It is in reflecting this 21st century world back to audiences, both within China and in the West, that artists ‘serve the people’ today.

When Neilson asked Capon to curate the second White Rabbit exhibition for 2013, Capon says that he didn’t hesitate for a moment before he enthusiastically agreed. When he began to select the works for the show, he was irresistibly reminded of his first visit to China in the early 1970s, at the height of the Cultural Revolution. He saw the slogan “Serve the People” everywhere; on posters, on exercise books and calendars, and graffitied in large letters onto walls all over Beijing. In the context of art, serving the people meant, of course, Socialist Realism. All other art forms were banned. One of the great stories of contemporary culture is the extraordinary flourishing of art in China since the ‘opening up’ period. Innovative, technically accomplished and, unsurprisingly, highly adept at creating many layers of complex (and sometimes well-hidden) meanings, Chinese artists are responding to a society in great flux. Capon believes the artists of today “serve the people” by liberating their spirits and giving shape to their anxieties, confusion and ambitions. Three threads run through this show, he says: fear, anarchy, and hope. In fact, I found more hope than fear; a healthy thread of cynicism and doubt; as well as the delightful sense of the ridiculous which is such a characteristic feature of Chinese art.

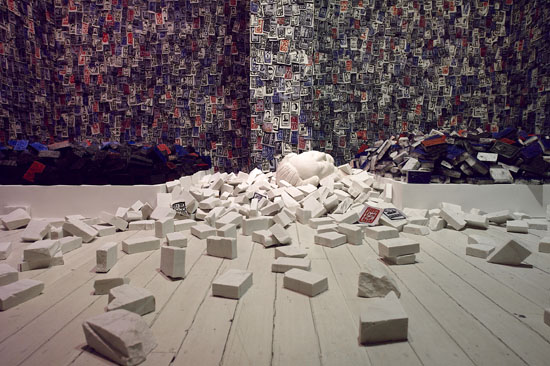

Jin Feng , A History of China’s Modernisation Volumes 1 and 2, 2011, rubber, marble, rice paper installation, image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery

Artists such as Jin Feng, Meiya Lin and Zhang Peili reflect on the recent and distant past. Meiya Lin’s video work ‘The Times are Summoning’ features rows of children in red Pioneer scarves lined up to perform the compulsory exercises experienced by generations of Chinese school students. Rather than representing the disciplined unity of the masses, in Lin’s piece the choreographed symmetry goes awry as the children reveal their individuality, their lack of coordination, and in many cases their utter disinterest in such an enterprise. Pioneering video artist Zhang Peili is represented by ‘Last Words’, which splices death scenes from heroic films made during the Cultural Revolution into one long and repetitive ham-acted drama. Actors playing revolutionary martyrs repeat their last words and death throes over and over, becoming meaningless rather than tragic figures.

Jin Feng’s ambitious installation, ‘A History of China’s Modernisation’, tells the story of China from 1911 to 2011. A room is filled with what appear at first to be broken shards of marble and black rocks, or (I thought at first) the coal briquettes used for heating in parts of Beijing even today. On closer inspection we realise that these are in fact traditional seals, or ‘chops’, with which the artist has printed images and text onto slips of rice paper which cover the walls.

An immersive installation, it reminded me of Xu Bing’s ‘Book from the Sky’, as traditional forms of carving and printing are subverted in ways which invite multiple interpretations. However in contrast to Xu Bing’s serene environment of hanging sutra scrolls and symmetrically arranged books, Jin Feng’s landscape is reminiscent of the piles of rubble to which Chinese villages and traditional neighbourhoods are reduced when the developers move in. Portrait images of significant players in the last hundred years of Chinese history are carved into the broken pieces of a marble statue of Mao, whose head lies on the ground like the relic of a lost civilisation. Words and phrases relating to aspects of this complex and contested history are carved into chops hand-cut from the tyres of a Chinese version of a Soviet tank. The artist says that China’s history is “extremely cruel”. There are blank, uncarved chops lying on the ground awaiting new developments, which he sees as likely to be no less cruel. Jin Feng’s long panoramic photograph of dusty peasants painted gold, mutely presenting their blank petitions, was one of the highlights of the previous White Rabbit show. This clever and cynical – almost despairing – installation is one of the lynchpins of Capon’s selection. Whether deliberately designed to do so or not, the audio of Zhang Peili’s work echoes through the space, creating an even more sombre mood.

Old favourites such as MadeIn Company’s ‘Calm’ – a field of rubble almost imperceptibly ‘breathing’, rising and falling with the rhythmic swells of the water bed underlying it – caused audience members to visibly ‘double take’ as they looked more closely and considered how the effect was created and what it could possibly mean. Nearby is Yao Peng’s ‘Five Masterpieces’, a copy of Mao’s ‘Five Essays on Philosophy’ from which the artist has cut out every word. The resulting tiny strips of paper are glued into a hard unreadable cube which is exhibited below the book, now full of neat holes where the words once were. Questioning notions of truth, wisdom and authority, Yao Peng suggests that language becomes meaningless and mutable once it is subject to the shifting tides of political power.

Shi Jinsong ‘Baby Stroller – Sickle Edition’ 200 116 x 65 x 80 cm, steel.

Then, from the sacrifices and cruelties of the past, the exhibition delves into the complexities and contradictions of the present. Shi Jinsong’s ‘Baby Stroller – Sickle Edition’ references a mythical boy super-hero called Na Zha. The artist created a line of “baby products” of which this frightening steel stroller covered with knife-like protrusions and spikes is just one element. A subversive comment on the highly competitive nature of parenting the ‘Little Emperors’ that are the result of China’s One Child Policy, the work also chillingly suggests the dog eat dog (which in Chinese, is “ren chi ren”, or “man eat man”) nature of contemporary Chinese society.

Shen Shaomin’s ‘Laboratory – Three- Headed Six-Armed Superman’ created of bones and bone meal and contained within a scientific beaker, or bell jar, evokes the maddest frontiers of science and biotechnology, a scarily plausible ‘brave new world’ where anything is possible and where scientific developments are likely to be dominated by the profits to be made by ‘Big Pharma’ rather than by any ethical considerations.

Yan Siwen, ‘His 4’, 2012, wet plate collodion on black glass, 40.6 x 40.6 cm, image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery.

All this black humour and pessimism is leavened with works that reveal a more introspective response to the world. A large ink painting by You Si demonstrates his characteristic swirls of brilliant colour created by dropping ink onto rice paper with an eye dropper; a reinvention of a traditional art form that suggests a macro-view of the cosmos and at the same time a microscopic view of cell structures. Fluid and lyrical, his paintings are inventive and strangely psychedelic. Yan Siwen’s black plate ambrotype photographs similarly reinvent a historical art practice, a variation of the wet-plate collodion photographic technique – a ‘Jurassic technology’, if you like – first developed in 1851. Part of a rising generation of Chinese photomedia artists who experiment with wet photography and alternative processes, Yan Siwen used this unpredictable technique to record her memories of a fleeting love affair. Personal and confessional, the resulting images are gently melancholic and filled with longing. Other highlights include Gonkar Gyatso’s image of a Buddha for our age, the deity traversed by roads swarming with cars and trucks and surrounded by planes; and Zheng Jianju’s witty series of simulated ancient ceramic urns made of tinted silicone. Like Ai Weiwei’s ‘Han Dynasty Urn’ series they ask us to question notions of the authentic and the valuable, at the same time satirising the ‘fake designer brands’ and recently manufactured antiquities so readily available in China.

Shen Shaomin, ‘Laboratory – Three-Headed, Six-Armed Superman’, 2005, bone, bone meal, glue, glass, dimensions variable.

One of the most significant works in the show is a re-working by conceptual artist Zhou Xiaohu of the famous 1974 performance by Joseph Beuys ‘I Like America and America Likes Me’, in which he spent three days locked in a New York room with a coyote. In Zhou’s ‘re-branding’ of the work, oil painting on a metal surface and video projection combine to create the sense of the ‘Steppenwolf’ circling the felt-wrapped figure of the artist. He describes much of his work as “automatic writing” and says he chose Beuys as his subject because of the way the artist liked to “deify and mystify himself.” He wanted to give the piece a new reading, making something hybrid to explore cross-cultural understanding and misunderstanding. In Zhou’s parodic homage, Beuys is trying to escape the locked room and dig an underground tunnel through the floor. Of his exploding weather-balloon work in the previous White Rabbit show, Zhou says “I did this out of mischief.” The continuing influence of Duchamp and Beuys on contemporary Chinese art, in addition to the profound impact of the 1999 Sensation exhibition (acknowledged by curator Pi Li in his talk at the University of Sydney earlier this year) continues to manifest itself in works that provide a wonderfully witty and wry commentary on the absurdity of the contemporary world. In a talk at the gallery on the opening weekend Zhou spoke about his conceptual piece (not included in this exhibition) ‘Detective Project, 2008, To Chase One’s Tail’, in which he hired ten Shanghai detective agencies to unwittingly follow each other, requiring each firm to provide the artist with a photographic, video and written report.

The works selected for the exhibition present a compelling narrative that reveals contemporary Chinese art to be adaptive, reflexive, enormously engaging – and revolutionary in a rather different manner than Mao intended. Exiting the gallery, back past those enormous pink underpants by Wang Zhiyuan, I reflect on Mao’s belief that artists must “change and remould their thinking and feeling.” In rather surprising ways, this is precisely what the artists in ‘Serve the People’ have done.

Pingback: White Rabbit Gallery exhibition, Serve The People, curated by Edmund Capon | Paul Costigan | A Word or Two

Could you let me know email to send details of new Beijing Calling exhibition please

theartlife@hotmail.com