From the road, Andrew Frost, on a big trip…

Home to Canberra

The road to Canberra is so familiar to me now, it’s only when I pass the McDonalds Sutton Forrest 100kms billboard on the southern side of Sydney that the journey starts to feel like I’m getting somewhere. There’s a hint of country there, and as the rest stops named for VC winners start to appear to the left of the motorway, and the promise of so-so coffee from the van parked at the layby just before the Picton Road turnoff for Wollongong, the road opens up – and I finally start feel free of the city’s gravitational pull.

Audio accompaniment is crucial on a solo car journey. There are a few hand-made and extensive playlists lined up on the iPhone, but for the first part of the trip it’s an audio book; The Affirmation, a lesser-known Christopher Priest novel from 1980. Part of the Dream Archipelago sequence of short stories, novellas and novels set in an alternate world of 10,000 islands, the novel features a split narrative – one apparently taking place in our world told by an unreliable narrator, the other within a story written by the narrator that mirrors aspects of the first. Of course, in a Priest novel, these narrative threads become entangled as the story-within-the-story reveals another layer – the character in the narrator’s story has written a story himself, this one about a fantasy world that includes a city called ‘London’ in a country called ‘England’. The audio book is read by Michael Maloney, a deep throated Englishman with an accent that has traces of the North. The novel’s prose is simple and easy to follow, but Maloney’s voice is like a hypnotist. Soon I am completely captured in the novel’s labyrinthine complexity. Listening to it sets the tone for the whole trip.

I’m on my way to Sale, in East Gippsland, to judge the John Leslie Landscape Painting Prize at the Gippsland Art Gallery. The journey would be close to a single, heroic 10+ hours on the road, probably more than 14 with sensible rest stops along the way, so I’ve decided to drive there and back in a long looping road trip that will take in a lot of country I’ve never seen, south via Canberra and Cooma, south east down to Sale, and then back over the Victorian Alps to Albury and the home.

Canberra

There are few museums in Australian that can do a collection show like the National Gallery of Australia, and there are two big shows to see there: American Masters and Power and Imagination: Conceptual Art.

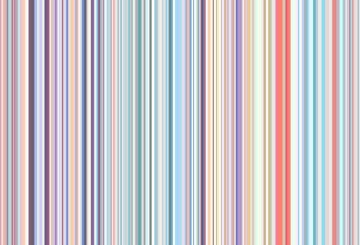

American Masters has had a lot of resources and promotion poured into it – there’s a handsome catalogue, and posters and banners are everywhere in Canberra. The exhibition’s website page is extensive and links to the works in the catalogue. The show covers 40 years of American art from 1940 to 1980, from pre-war parochialism to the fade out of modernism, grouped from the New York School, Colour-field Painting and Post Painterly Abstraction, to Pop, Minimalism, Conceptualism, Anti-form (Land Art and soft sculpture), Photorealism and Funk, and concluding with Light [neon and fluro sculptures with mirrors]. The show has been carefully curated to do two things: first, showcase some jewels from the collection such as Jackson Pollock‘s Blue Poles in an historical context through a juxtaposition with earlier work, the work of peers and contemporaries; and second, to carefully avoid suggesting that this show adheres to the post-war narrative of art movements. Sure, these things happened, some were contemporaneous, others more distanced in space and time, but let’s not go all Alfred Barr.

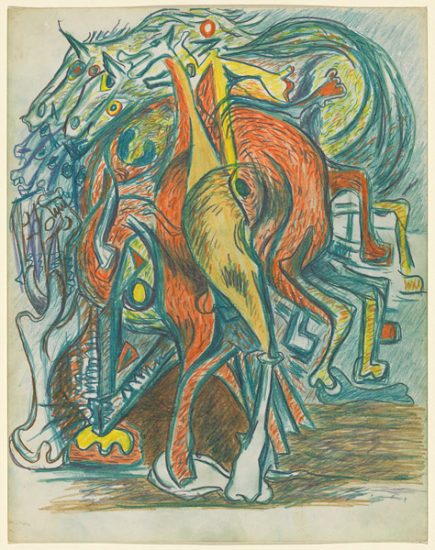

Jackson Pollock, Untitled, c.1939-42

As I walk around the show getting the sort of goosebumps one has when seeing a brilliant greatest hits collection, I encounter two primary school groups sitting on the floor; one group is listening to a guide talk about Blue Poles, while the second group sits a little further back awaiting their turn in front of the iconic picture; in the meantime they’re being shown a video on an iPad priming them with some basic Pollock-facts: he was an alcoholic, he was into emotional honesty in his work, and he was killed in a car crash. I must resist the urge to jump in front of the kids and say, look over there – Marc Rothko! Lee Krasner! There’s more to this than greatest hits kids…

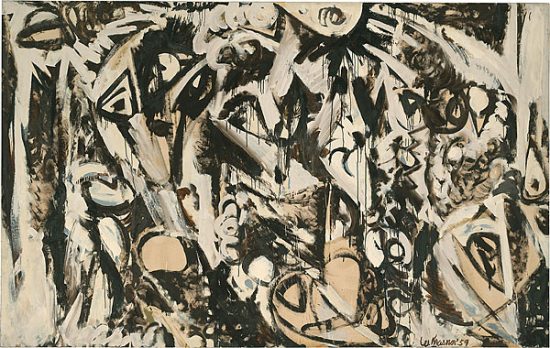

Lee Krasner, Cool white, 1959.

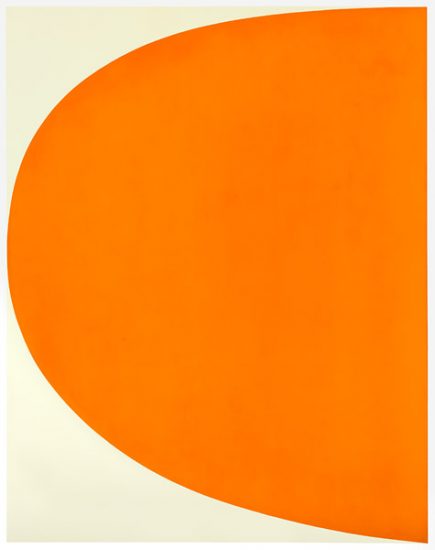

Like a lot of people of a certain age, Surrealism and Pop Art were the mother’s milk of an early education in modern art. They were, and remain, provocative but legible concepts that you can understand by simply looking – no explanation is really required. American Masters features some key works from the Pop period. Andy Warhol‘s silver Elvis catches my attention, but I realise that the work that really speaks to me now, and continues to mature in its visual appeal, are the majestic works of abstract minimalism – pictures by artists such as Elsworth Kelly, Morris Lewis, Clyfford Still, Josef Albers – paintings that sit well with the NGA’s sculptural installations by Robert Smithson and James Turrell.

Ellsworth Kelly, Orange Curve, 1964-65

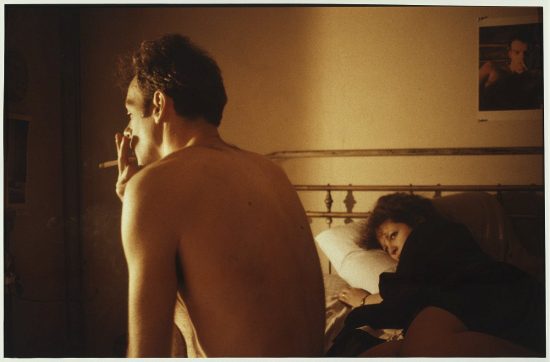

Exhibitions with a broad sweep of time and the meeting of an array of styles, intentions and outcomes can tend to feel arbitrary in the way they conclude. The final rooms of American Masters have the good sense to include among all the grand gestures of the male painters and mystic sculptors some photography, the look and style of which suggests what was to come in our age of phonotony – the work of Nan Goldin and Cindy Sherman, artists who created images suggest on the one hand, the honesty of an intimate moment captured in an image, and on the other, the performance of an alternate self. Although the show is situated one of the NGA’s galleries just about forms a circle, there is a definite sense of something more to come as you leave…

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, NYC. 1983

Upstairs somewhere in the NGA is Power & Imagination: Conceptual Art. Like American Masters, it too is a collection show, but not all exhibitions in major museums are born equal. It hasn’t had the flagpole treatment, it doesn’t have a catalogue and the exhibition’s web page is a single page with no links, no list of works or artists in the show. The exhibition is staged in a far upstairs corner of the NGA, an exhibition space so remote I need to ask two guards where it is. At one stage I think it’d be the perfect conceptual art joke if it didn’t actually exist in physical form – if it was just an idea for a show and punters would be required to search in vain. The second guard, who just happens to be sitting right outside the gallery where the real, actual show was located, waves me through the door with a happy smile.

Gunter Christmann, Berliner Haut, 1973. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas.

Giovanni Anselmo Entrare nell’opera [Entering the work] 1971, gelatin silver photograph.

What’s remarkable about Power & Imagination is how comprehensive it is in scope and range – Australian artists are well represented, Ian Burn of course, but also important artists such as Bonita Ely, Sue Ford, Gunter Christmann and Richard Tipping are represented. The wall blurb tells me:

“Writing from the thick of [conceptual art’s] development in 1968, critics Lucy Lippard and John Chandler observed ‘a profound dematerialisation of art’ that they believed could result in the object ‘becoming wholly obsolete’. With this in mind, Power & Imagination gathers together works of art poised at the junctures of dematerialisation, transformation, appearance and disappearance.”

One of the legacies of conceptual art is its rejection of the kind of aesthetics that were the basis of many of the pictures that hang in American Masters. The ‘dematerialisation’ of bourgeois formalism, and the embrace of an idea that would bring art back to its fundamental essence – concept and gesture – ironically produced the very thing that [I am sure] most artists working during the first flowering of conceptual art would have [and would still] reject: a style of art. This is not a bad thing. In fact, I love it. Walking through Power & Imagination was thrilling in a way that its downstairs cousin was not – this was like flipping through your old late 80s 12″ dance mixes and finding some noise art vinyl. This is the real deal.

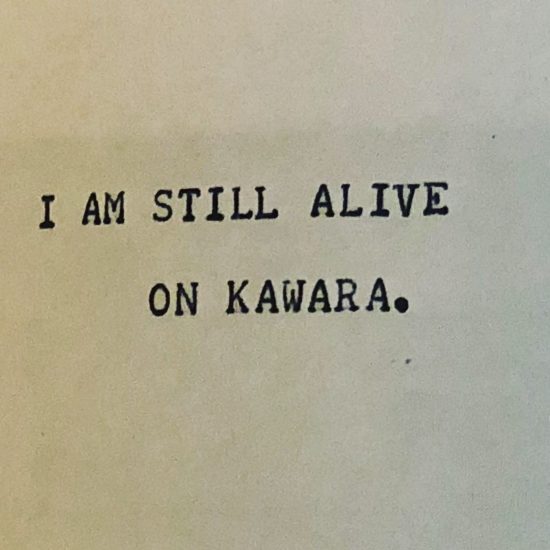

On Kawara, I am still alive, 1978. Telegram.

Michael Craig-Martin, An Oak Tree, 1973. Glass of water, glass shelf, chrome brackets, printed text.

Happily the conceptual art project of dematerialisation was incomplete since, if it had achieved that aim literally instead of just metaphorically, there would be no show. Looking at On Kawara‘s telegram, and Michael Craig-Martin‘s An Oak Tree, I remind myself that, as someone familiar with this kind of work and the subtleties of how to read it, my take is not what casual visitors to the gallery would necessarily make of it. I remember an older gentleman, who was a mature age student in a UTS writing course I did in the early ’00s, telling a class of his encounter with An Oak Tree and, in a mounting rage, his utter incredulity that such a work existed, that the gallery would show it, let alone buy it for the collection, and how the artist was clearly taking us all for suckers. I tried to mount an argument in its defence citing the usual lineage of conceptual art works from R. Mutt onwards but to no avail. I couldn’t convince him, or even get him to acknowledge that a conceptual art idea was a valid form of artistic expression. I always think of that incident when I see works like An Oak Tree and think, thank god they exist.

Canberra to Sale

Driving into country for the first time is a special kind of experience. With the sun above as I head south, the road over the high country opens up, and the traffic outside Canberra thins out until I am driving in my car, alone on the blacktop. Sun Araw is the early morning playlist, a slowly evolving psychedelic accompaniment as I head for Cooma. [Side question: is Queanbeyan the worst town in Australia? It looks and feels like the Western suburbs of Canberra, but it’s actually across the state line in NSW. The motel I chose online turned out to be not a quaint, 60s style series of cabins, but a strip of self-contained rooms with malfunctioning air con situated right next to a four lane highway. If you don’t want Maccas or KFC for dinner in QB, there are two options; a Thai restaurant with a basic green curry for $25 takeaway, or the pub. I choose the pub. Inside it’s full of Goth kids and their parents playing bingo while the game master/DJ plays an excruciating selection of Oz Rock greatest hits at ear splitting volume. Out on the street some junkies argue over something [I fucken’ told ya!] and the walk back to the motel is a route that passes a David Lynch location…]

As I arrive in Cooma, I wonder if the town has a second hand book store. Aside from looking at and judging art, my tour has another purpose: to find vintage fiction paperbacks and hardbacks ‘in the wild’ [as the serious collectors call it] in Canberra and beyond. I was quite successful in Canberra finding a few first edition Golancz hard backs, and a selection of ok to very good paperbacks, but you always need to keep looking. Just as I enter Cooma I wonder what the chances are, and as I glance to the left, yes, there is a second hand and collectable book shop right there with a parking space just outside! I pull over and go inside. It doesn’t seem promising – there are an awful lot of science fiction authors in the world who are bad writers – and the bookshop is full of books by people I’ve never heard of. On almost the last shelf, mis-shelved in the wrong place, is a paperback of William Gibson‘s Neuromancer. Good to very good condition. First UK paperback. $7. The gods have smiled.

The drive down towards the coast of Victoria is spectacular. The road is almost empty of other cars and only the occasional truck hauling forest timber slows me down. In the audio book, the story has advanced to the Dream Archipelago itself, and Priest’s language is evocative – one country sounds a bit like Spain or Mexico, and the waters of the capital’s harbour are ‘bottle green’. My head is full of images from the book that do battle with the scenery outside the car…

Sale

Oil was discovered off the Victorian coast near Sale in the mid-1960s. Major multinational oil companies moved in and put a lot of money into the town and region and Esso built their corporate headquarters, a massive Brutalist carbuncle just near the Port of Sale [a 19th century navigable canal], now the refurbished home of the Gippsland Art Gallery. Simon Gregg, the gallery director, tells me that, in the 19th century, Europeans had to approach the region by going over the Victorian Alps because the stretches of land between the town and Melbourne were a series of swamps and wetlands. After these lush environments that were rich with birdlife and abundant native foods were terraformed by draining the land, the whole region became an even richer pasture and farming region, dead flat in all directions and a perfect place for an air force base. The story of the oil companies and the transformation of the land put me in mind of A Dream of Wessex, another Priest novel, where a shared, multi-player virtual reality project goes awry when the wrong person joins the team. I am here to judge an art prize. I could be that person.

At the Matador Motel [mid-70s faux Spanish style, built for visiting oil executives[ I reflect on the process of judging. I think I must have done more than a dozen in the last 15 or so years. If I’m doing the judging solo, I walk around and look at each work in turn, spending way more time with each picture than if I were just walking around a gallery. That first pass usually suggests a short list but the trick is not form opinions too soon. Then a coffee, then another go around, spending more time with works that seem to stand out. At this point I try to decide whether the attraction is superficial, or there’s something there a little deeper. Sitting in front of paintings usually does the trick. For the John Leslie Prize there are about a six or eight paintings that I like, maybe four that are serious contenders. Then I finally arrive at a decision. This often feels like that sensation you can have when you tell someone you love them. Let’s make this thing real!

The winner is Vanessa Kelly‘s Wyatt Brothers Chicory Kiln, Corinella Gippsland [2018. Acrylic on linen, 90 x 120cm]. I open a bottle of wine in my motel room and toast the work. It’s a good one.

Sale to Albury

You could do some research about a drive, or you could just pick a road and take your chances. I decide on the second option. Over the Alps.

Albury

The final leg on the tour is an overnight stop on the border. I had not visited the regional gallery, now known by the grand title of the Murray Art Museum Albury, but I had seen the plans for the new galleries when they were designed and saw the building under construction. The first thing that strikes me as I walk in is how small it is – or to put that another way, it’s surprising how much ground floor space is given over to the gallery shop, and various commercially rented meeting rooms. The main space is occupied by a single work from the show Immortality, which is a projection and some old cinema style seating. Adjacent are two small gallery rooms with works form the collection on show The rest of the Immortality show, and the other, bigger galleries, are up a grand staircase.

For Australia’s regional galleries, the trick to survival is to do two things well: serve the local community, and stake a claim for being a place that people from outside the region are going to want to visit. Many galleries have tried to emulate the ‘Bendigo effect’ – putting on expensive crowd-pleasing shows, hopefully with some overseas artist names attached. If people are going to travel to see art in the regions – and sadly not many people seem to do that – then regional galleries have to compete on an equal footing with city galleries and museums. It’s always seemed to me that that is an expensive and not always successful way to do things. Destination collections built up over decades can prove very effective, as can some daring and interesting curating. On my visit, MAMA has tried to do both.

Immortality is a show that features the work of some excellent Australian and international artists, including Susan Hiller, a personal favourite of mine since the 1980s. I don’t want to upset the artists in the show, or indeed the MAMA curators, but the show is boring. It’s perfectly respectable, exquisitely installed, and beautifully curated – you can almost feel all the parts joining together like slots in a paper model – but it’s the kind of show that can be seen anywhere. Sure, the local audience wouldn’t get to see this work if it weren’t for MAMA, but that alone isn’t a reason to like it. I suspect that the show next door is what people in the Albury-Wodonga area is more their cup of tea.

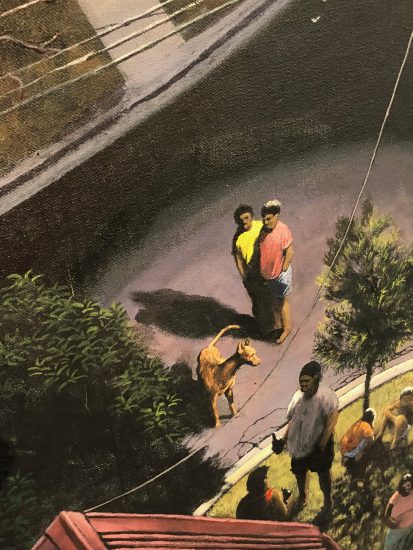

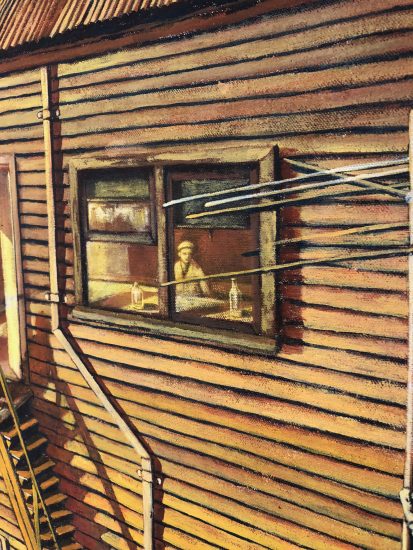

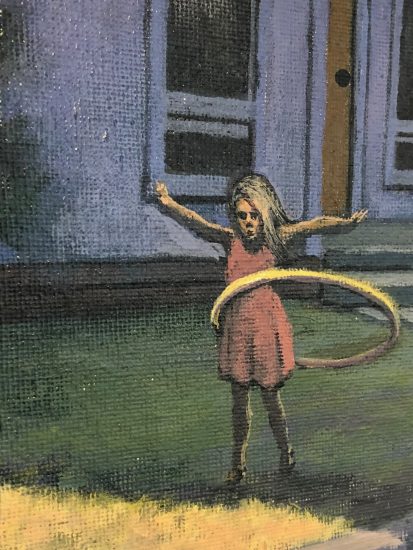

Next door is – take a deep breath for this one – the Brindley Family Galleries & Quest Albury and Quest on Townsend Gallery spaces. In it is Leon deMontignie: The Life and Death of an Unknown Artist I had never heard of deMontaigne before, but then it turns out very few people had. The artist lived in Albury and the North West part of Victoria and was essentially homeless for long periods. Neither a driver or bike rider, the artist, who had French, Scottish, German and Yorta Yorta heritage, led a nomadic life hitching rides to travel, and to observe the world from the passenger’s seat. Somehow he also painted. He was blessed with a photographic memory and his works – acrylics on canvas – are unique snap shots of modern life.

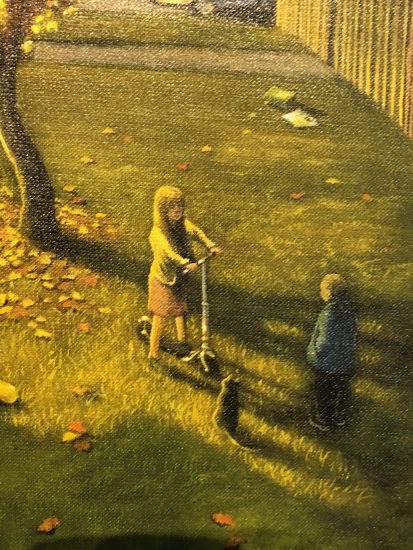

The perspectives and elevated views of his paintings are unique, an original mixture of styles and themes, that are like an antipodean version of Edward Hopper, or closer to home, a spiritual cousin to James Guppy‘s paintings of surreal moments in strange suburbia.

The exhibition collects together deMontaigne surviving paintings along with the illustrations that were his most well known works – the illustrations he did for Peter Klein‘s Mudpoo kid’s adventure stories. The lighting in MAMA’s gallery are spot lighting the works so it’s almost impossible to get pictures without the camera’s shadow. But I persist and get in close and then become enchanted with the details in the pictures. deMontaigne painted from a God’s eye view, looking down on the people in a town’s night time streets, and in my favourite, a scene that is bathed in a kind of Biblical light, a meeting between a girl on a scooter, a boy, and cat.

The show feels miraculous, like the discovery of something profound. It’s not the kind of thing you’d see just anywhere.

I promised Leon deMontignie that he deserved to be recognized in Australian art and will do as much as humanily possible to show case his work . The feed back we have received from his two solo exhibitions at Federation University Churchill which broke all records and MAMA’s is mind blowing and wish Leon was alive to witness the pleasure his work has given to many people .. My next goal is to attempt to have an exhibition in a major gallery . I see his work as ” Lifescapes” instead of the term landscapes and they need to be seen .