It’s only been a couple of weeks since the Biennale of Sydney opened but already it feels as exciting as last week’s milk. Which is to say, not very exciting at all, not very interesting and possibly a bit stinky. BOS 2006 is a curious success and also a strange kind of failure. Dr. Merewether’s organisational principle [don’t call it a theme] of looking at artists who are caught in the worldwide diasporas of a mobile population with money and time on their hands to make art about their situation, has been by far the most successful Biennale quasi-theme in years.

Hany Armanious, Intelligent Design [detail], 2006.

Polyurethane on form ply, 30.5×237.5x8cms.

Courtesy Roslyn Oxley 9.

Two years ago during BOS 2002, Roslyn Oxley had an exhibition of work by Hany Armanious. Like many galleries around town trying to hitch their wagon to the BOS with exhibitions by artists with some sort of international profile or, at the very least, exhibitions by their best artists, Oxley has a number of artists with international profiles who could conceivably fill that spot but few have as much artistic credibility as Armanious. Of all the Grunge alumni, it is Armanious who has stayed the closest to his roots, exploring the elegant yet crusty beauty that is his trademark. For 2006 Intelligent Design is a show of sculptural works that display his dexterous use and understanding of materials. The title piece of the show is elegant and simple and looks as though it could have been made back in the heady days of the early 90s. A series of polyurethane hooks arranged on a backing board present the viewer with a repetitive visual field. In the middle of all this is a small polyurethane horse’s head turned upside down so it too could be used as a hook. In the context of the rest of the piece, it’s a pretty funny visual gag playing on the similarity of the forms, but given the title of the work, it also plays on the idea of conspicuous parallel evolution. How can an inconceivably complex organism exist without the intervention of a higher intelligence to guide its creation? Or is it just a coincidence?

Hany Armanious, Bubble Jet Earth Work, 2006.

Glycerine, worm castings, air. 159x80x140cms.

Courtesy Roslyn Oxley 9.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, Armanious’s work makes similar kinds of logic inversions in various spectacular ways. The macabre The Danger in Extracting Meaning is an elaborate visual pun that offers substantial aesthetic thrills, from the fake snow that blows around inside the box to the banana legs on the bottom of the piece to the electric jug plug that powers this Jack The Ripper-meets-art criticism diorama. In the work Bubble Jet Earth Work Armanious has created a machine that makes drawings on long rolls of paper. Using a bubble blowing machine and a slowly moving sheet of paper, the froth from a can of Guinness [along with some glycerine and worm castings], stains the paper in delicate brown circles, then piles up in huge mounds in the gallery. The machine is a thing of beauty, a witty and insightful demonstration that no aesthetic system can exist without outside input. Whether this is an example of a deep religiosity we can’t say, but from the point of view of the purely secular, Armanious makes works of real authority that demonstrate an almost peerless command of materials.

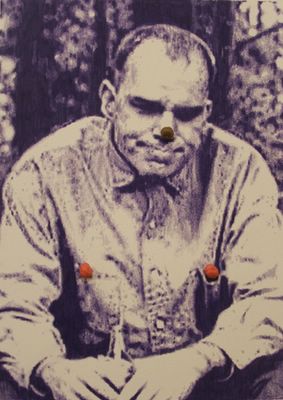

Rob McLeish, Big Mouthfuls Forever #4, 2006.

Pencil and chewing gum on paper, 29 x 39 cm.

Courtesy Esa Jaske Gallery.

Rob McLeish’s Lick The Loser and Make Them Stick at Esa Jaske Gallery has a lot connections to the work of Armanious and other artists of the early Grunge period and it’s the kind of contemporary art that people who don’t know anything about contemporary art will look at and say, what the hell is that supposed to be about? If you don’t know anything about the last – ooh – 30 years or so of art history, of conceptualism, of contemporary European photography, of theories of the abject, or had an eye for a joke, you’d be scratching your head in complete befuddlement. On the other hand, if you did know about these things then you might rate McLeish’s work as highly as some of the younger artists in the Sydney art world rate Melbournite McLeish. McLeish takes images he finds on the internet and then traces the photos with pens on a light box giving them an almost photorealistic look to what on closer inspection turns out to be messy, scratchy, graffiti-like drawings of drab American kids in drab backyards, lolling about on trampolines, making faces or getting dirty for their web cam. Let’s call his work International Abject because there’s a lot of this kind of stuff around [cf SLAVE] and it appears not to have borders. If McLeish can claim any individuality to this work it’s through the choice of the images and the particularly distressed and artless aura they give off, but aside from a couple of works that raise a laugh – Big Mouthfuls Forever Series #4 which features the big doofus from Slingblade – there aint nothing going on here but the rent. Interestingly, the connections to McLeish’s work are traceable to his Sydney contemporaries, and perhaps that’s why a whole slew of artists in Sydney reckon this guy is the bee’s knees. However artists such as Chris Hanrahan, Todd McMillan, Matthew Hopp, Ella Barclay and Viki Papageorgopoulos [among others] have cottoned on to the fact that the difference between trash and treasure is the surface gleam and the idea lurking behind it. Without the first thing, it’s tough going, without the second, you’re just wasting your audience’s time. But more crucially you have to demonstrate you know this fact, and you have to do it in the work itself.

Linde Ivimey

Jacob and the Angel II, 2006

Steel armature, cast acrylic resin, dyed cotton and silk, natural fibre, cast and natural eagle, sheep and chicken bones, 92 X 88 X 33 cm.

Courtesy Martin Browne Fine Art

No one would mistake Linda Ivimey’s work for anything but a highly traditional and exquisite aesthetic experience. Her elaborate sculptures in the show Old Souls- New Work at Martin Browne Fine Art take their cues from the stories of the Saints, with guest appearances from The Four Horsemen of The Apocalypse and The Twelve Apostles. The various sculptures feature bones and hair, costumes and sculpted faces under sack cloth [sans ashes], frozen moments of mutual destruction and endless penance. Ivimey’s sculptures are incredibly evocative, reaching down into the root mythos of Western society, bringing up imagery that, while it may seem pretty obscure to those without knowledge of the life and miraculous deeds of St. Emmeranus [for example], one feels it as much as you might know it. It’s as if figures from a Peter Booth nightmare have stepped out of the painting and into a three dimensional world. There is also a very dark sense of humour at play, a small figure in one corner of the gallery, a child like figure with furry feet and a body made of chicken bones seems to smile back at you. We urge any visitor to this exhibition to take whatever precautions against evil spells they feel is necessary.