Andrew Frost takes a trip upriver into the psychic jungles and becalmed waters of the paintings of Laith McGregor and Alexander McKenzie…

In the far corner of one of the continents of text that cover Laith McGregor’s Ping Pong Paradise there’s a fragment of a $20 note. Next to it there’s some hand written text: “Antonioni’s interest in the confounding duplicity of our mental and physical lives, the inner and outer worlds which fiercely compete to consume man, is the impetus behind The Passenger.” Then there’s a lot more text about the film and Antonioni [unattributed source] which ends with a portrait of red-capped Bill Murray from The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou and then more writing, more sketches, stains from the bottom of coffee cups, some phone numbers, shopping lists, and much more, in four sections on a single, huge piece of paper, with a larger-than-life-size self portrait of the artist on one half, a monkey’s head on the other, and the whole thing mounted under glass on a table tennis table, complete with two paddles and ball, arranged just so.

This quite astounding work was the centre-piece of McGregor’s recent exhibition Laith McGregor: Ohne Titel (Them Listless Folk from Apocryphal). The ‘ohne titel’ bit translates from German as “untitled” or “without a title”, but as you can see from the parenthetical afterthought, the show did in fact have a title. So who was listless here? Certainly not the artist, as could be seen in the amount and variety of work on display. The exhibition included paintings, drawings, sculptures and a single-screen video work that featured on one side of a split screen the artist having a snooze [or meditating] under a warm blanket, while on the other side of the screen he is seen walking across the surface of a lake barefoot. The title of that one was Mind Eye. So perhaps the listlessness was a spiritual malaise rather than a physical one, and McGregor was invoking the hippie spirits of the past to empower the journey of his show, to give it a purpose and an objective, and to arrive up river with the metaphorical Kurtz amid the encampment of text and image in Ping Pong Paradise…

Laith McGregor, In the Future, 2012. Oil on linen, 168.5 x 168.5cm.

This idea of a theme of a ‘journey’ in Ohne Titel was inescapable. The first room of the show featured a number of large oil on linen paintings. Themes and images recurred: men in top hats and long coats adrift on sail boats, ragged figures with paddles on crudely constructed rafts, a crouching figure on the prow of a canoe, top hat, cigarette in mouth, one hand extended as if in about to point ahead. The execution of the paintings would come as quite a surprise if you only know McGregor from his Biro on paper drawings. Where those carefully and immaculately executed images of men with fantasy beards were self-contained and marooned, these images sat atop background washes of paint with long streaks, runs and pools, all layered and perfect, but free and suggestive. This space had depth and detail beyond the foreground. Into this space McGregor had found faces and profiles, tiny details of drawing suggested by the chance shapes, which he teased out and then camouflaged into the background. The foreground figures were more definite, yet had the same ghostly feel.

This was a world with its own peculiar rules and inhabitants lost in a Conradian narrative – and the colours [blues, greens] were so strongly suggestive of the early 1970s I felt compelled to search out my copy of Popol Vuh’s spacey soundtrack to Werner Herzog’s Aguirre: The Wrath of God [1972] and zone out to the Krautrock vibe. How fitting. In Herzog’s film a band of conquistadors head off into the jungle looking for Inca gold but end up on a barge floating slowly down river, seeing strange things up in the trees – a whole three-mast sailing ship caught in high branches – but disregarding them as a hallucinations brought on by starvation. The river journey theme in McGregor’s show was compounded by the inclusion of a sculpture Untitled [Boat], a freestanding piece that looked like half a canoe rising out of the gallery floor.

Somewhere buried in the text of Ping Pong Paradise… was a reference to Ban Jas Ader. I made a mental note to find it again and write it down, but it was lost in the text, which was oddly appropriate. Ader is the patron saint of artistic failure, or success if failure is the theme, as it was for him. He died in 1975 attempting to cross the Atlantic in a 12 ½ foot sailboat. As his memorial website explains, “Ader embarked on what he called ‘a very long sailing trip.’ The voyage was to be the middle part of a triptych called In Search of the Miraculous, a daring attempt to cross the Atlantic […] He claimed it would take him 60 days to make the trip, or 90 if he chose not to use the sail. Six months after his departure, his boat was found, half-submerged off the coast of Ireland, but Bas Jan had vanished” [janbasader.com].

The story of a journey is the metaphorical narrative of self-discovery, the so-called monomyth or the “hero’s journey” that is invariably populated with archetypes and embodied metaphors, and which ties together every ‘road’ narrative ever written from the stories of Moses, Buddha and Osiris to The Wizard of Oz, Star Wars and The Matrix. The journey typically involves a passing between the physical realm of the real world and the world of spirits and phantoms, illusion and deception. As to whether the traveller comes back depends on the individual story. In Ader’s case, he didn’t make it, but his death has left contemporary art with a variation of the monomyth that handily encapsulates a modern Romantic sensibility.

Which brings us back to Ping Pong Paradise – the Rosetta Stone of the show. It was located upstairs at Sullivan & Strumpf, surrounded by more of McGregor’s drawings [one of which appeared to be a portrait of Ader, another was a spiral of biro lines creating a vortex that led to a point of light called Being Human). And then the text, that endless ocean of text, ideas and ruminations, half thoughts and jottings, made over the duration of the creation of the rest of this rather fantastic show. Was it the river of Heart of Darkness or the ocean of the documentary Deep Water that tells the heart-breaking story of the madness of lost sailor Donald Crowhurst? Either journey leads to a confrontation with the self – the universe, and everything in it.

In the aforementioned The Passenger, David Locke [Jack Nicholson] assumes the identity of another man for reasons that remain ambiguous – maybe he wants to investigate arms dealing in Africa in the guise of a deceased trader, perhaps he just wants to escape from his life, either way, the film ends [SPOILER] with Locke killed under mysterious circumstances in a empty hotel in a dusty village in Spain, a place of empty streets and shuttered windows.

Alexander McKenzie, Through the Hedge, 2012. Oil on linen, 76 x 76 cm.

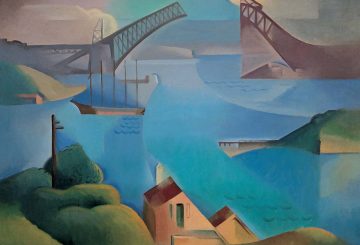

If McGregor’s show was all about the journey, then the work of Alexander McKenzie was all about the place on the other side, that strange and cold world of becalmed waters, mysterious signifiers and obscure topiary arts.

McKenzie’s show Arboretum was a suite of two dozen large oil on linen pictures, a host of smaller works on board and two drawings. Like McGregor, McKenzie is no slouch when it comes to making work and, with his careful technique of smooth brushless surfaces, it must have taken an aeon of studio work to achieve the final selection. McKenzie’s work is repetitive, habitually returning to the same scenes and themes – compositions are reworked and refined, a change in the placement of water courses, canals or roads, a light source here or there, but the basic templates of the pictures are very much the same.

Take for instance The Wrapping of The Trees [2012]. It’s huge at 122 by 167 cms. A group of four trees are lined up, the inner pair without leaves. A concrete path encircles the garden, a trio of empty chairs on the grass. Beyond a railing is a lake and in the distance mountains lost in fog. The drama of the picture is in its stillness – there are no figures here, no action, an effect compounded by half the picture taken up with sky. In Arboretum McKenzie tried a number of variations on this composition all to equal effect. You find variations in Looking for the Greenhouse, Fighting Fables and Zig Zag Bridge.

Other works, such as The Island is a Mighty Fortress [2012], is reminiscent [if not a direct quotation] of Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of The Dead [1880]. Böcklin was a Symbolist with a distinct strain of Late Romanticism ghosting his painting, and McKenzie’s work combines that same uneasy marriage of symbolism and sublimity. What is so compelling about McKenzie’s paintings is that there seems to be no reference to a decodable symbolic language. The clue, however, to the show’s intent is in the exhibition title. An ‘arboretum’ is a place where “…an extensive variety of woody plants are cultivated for scientific and educational purposes and ornamental decoration” [thank you Wiktionary]. This is far from a natural landscape – it is man made, altered – and designed to be viewed. Where classical Romantic landscape painting was about evoking the immanence of divinity, and the lowly place of man within the majestic scope of nature, the absence of God in the contemporary, secular world has left landscape painting without its grand heritage. McKenzie may just as well be painting Stubbs style horses because, like those stallions, this is a genetically modified and shaped place where God has been ousted by man. If I had to think of an appropriate musical accompaniment to these images, it wouldn’t be the freaked out stoner classics of German synth music, but Samuel Barber’s Adagio For Strings, Opus 11 – that overwrought, overstated, yet perfect blend of Romantic tragedy and steely modern relevance.

Representational art offers an idea of escape, and landscapes are a fantasy of place. You imagine being in McKenzie’s pictures and it’s an odd sensation. It’s perpetual winter, the sun rarely shines. There are no people here and night is coming. In the atypical Through The Hedge a path runs to a circular hole cut into a hedge. The scale is uncertain but if the path is anything to go by the bush is huge. It looks a lot like a portal. Perhaps if you stepped through you could get back to this side of the mirror.