Reporting live from Beijing, Luise Guest looks at images of women in contemporary Chinese art…

Late Autumn in Beijing alternates glorious blue sky days with others on which the pollution levels soar into the ‘alarming’ zone and people with masks covering their faces are glimpsed through mist and fog on grey streets under grey clouds. The schizophrenic weather conditions mirror something of the paradoxical nature of contemporary China. On one street you see old men in Mao suits playing mah-jongg on the corner, while in the next you are as likely to find a Lamborghini showroom as a snack cart selling dumplings. These paradoxes extend into the art world too. The pace of change in China has been so swift and dislocating that each new generation of artists essentially inhabits a different country, with different experiences, ideas and beliefs. On every construction site billboards loudly proclaim: “This is my Chinese Dream.” This dream, and what it might entail for different generations in China – and what that might imply for the rest of the world – is definitely contested territory.

I have been fascinated to discover these generational dissonances as I have met with artists during a two-month stay in Beijing. My particular project has been to interview female artists. Just as the social forces in China have swept away old certainties, so too have ideas about gender and the roles of women been changing, albeit in ways quite different from what one might expect.

Recently this has come to the forefront of public discourse, as the term “sheng nu” (“left-over women” – defined as single women over the age of 27) has gained increasing traction in the media. The following delightful piece was published on the website of China’s state feminist agency, the All-China Women’s Federation:

“Pretty girls don’t need a lot of education to marry into a rich and powerful family, but girls with an average or ugly appearance will find it difficult. These kinds of girls hope to further their education in order to increase their competitiveness. The tragedy is, they don’t realize that as women age, they are worth less and less, so by the time they get their M.A. or Ph.D., they are already old, like yellowed pearls.”

Despite the gender imbalance created by the One Child Policy and a preference for boys resulting in an over-abundance of men seeking wives, it seems that contemporary Chinese culture punishes women for being over-educated, over-ambitious and financially independent.

In street fashion, advertising, and, yes, even in the hallowed space of art galleries, I have been observing a kind of hyper-femininity. Representations of the feminine in some of the less illustrious galleries in the 798 Art Zone range from imperial maidens and concubines, reflecting nostalgia for a patriarchal past and its certainties, to fibreglass stilettos covered in spikes, an indication of current anxieties. Young men are nervous. They feel enormous pressure to be rich enough, and successful enough, to attract girls and find a wife. The famous quote from a TV dating show, from a young woman who said she would rather weep in the back of a BMW than laugh on a bicycle, is cited often as evidence of women’s materialism.

Han Yajuan, Travel Alone, 2007. Oil on canvas image courtesy the artist.

To find out more, I spoke with three artists who explore some of these ideas in their work.

I met Han Yajuan in her bright apartment and studio in the new area of Wangjing, where she looks down over block after block of high-rise apartments and sweeping expressways, a view she describes as “depressing”. Her work has been seen recently in Australia in the ‘Go Figure’ exhibition, curated by Claire Roberts from Uli Sigg’s collection at the National Portrait Gallery, and in ‘Far East Duet’ at the ACAF Project Space in Melbourne. She is represented in New York by Eli Klein Fine Art.

Born in 1980 in Qingdao, Shandong Province, and earning her MFA from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, she is sometimes described as an artist whose works embody the collective unconscious of her generation, which seems rather a heavy burden. Her paintings reveal her interest in Japanese design and animation, as well as fashion, and reflect the culture of ‘cuteness’ (in Chinese, “Ke’ai”) prevalent in contemporary pop culture. In China, young (and even not so young) women are expected to behave in ways which are winsome, even child-like. ‘Travel Alone’ depicts a cute, big-headed, bling-adorned cartoon girl climbing into her red sports car wearing Dior glasses. She carries bags labelled Prada and Chanel. Fake or real, they reflect the current obsession with designer brands as symbols of wealth and success. Han Yajuan reveals the current anxiety about the lives of young women, the ‘material girls’ who want it all, and want it now. ‘Fashion Week’ represents the frantic busy-ness, but also the emptiness, of this world. In response to my suggestion that her paintings are a critique of contemporary life and materialism, she says, “I was just trying to present what I see…what exists. Twenty years ago a bicycle was a luxury, but things change. There is so much pressure; the speed (of life) is so fast. I am trying to present my point of view and also to give people an opportunity to see their own lives.” Her generation have not experienced the hardships of the past, and are experiencing the loneliness, as well as the material comforts, of an entirely different kind of society.

In sculptural works such as ‘Super Starlet 6’ the cloying cuteness is undercut by a disturbing sense of identity crisis – these are essentially faceless beings, literally from the assembly line. Looking at these works before I met the artist, I wondered what she intends to communicate about the lives of Chinese women today. Are the creatures she represents victims of new social pressures, or are they empowered and materially successful beings? Is it celebration, or criticism? The answer, as is so often the case in China, is equivocal. Han Yajuan’s female figures are, and also are not, self-portraits. She is a participant in, as well as an intelligent observer of, the culture in which she finds herself. Self-possessed and confident, with her deep voice and disarmingly infectious laugh, she is fully aware of the dark side of the glamorous world she depicts: a world of corruption and karaoke bars; mistresses and designer handbags. But she is pragmatic. “From a very primitive perspective,” she says, “it relates to the uncertainties of life – we should pursue the things that make us happy. It’s personal. It’s about what makes me happy. There is a part of me in all those figures.”

Han Yajuan, Super Starlet 6, 2011. Color paint on tin bronze, crystals, 45 x 36 x 40 cms. Image courtesy the artist

“I am from the eighties generation”, she says, identifying the strictures of the Chinese education system as well as the Japanese cartoons she loved as a child as key influences on her thinking. “My early works are about individualism and uncertainty. Later I changed my perspective to stand on a higher point and look down upon a whole complex and contradictory world.” When she began to create these elaborate multi-dimensional compositions, she was initially filled with self-doubt and uncertainty. Working towards a solo show in New York next April, she says, “I am trying to connect doubt and uncertainty with very concrete things. You can see the materialism, you can see the fashion, but this is just recognition. I know why I am doing this. I know what I try to achieve. It is for people who maybe don’t have the time to see this, to look at these things.”

Rather surprisingly, given their apparent celebration of consumerism, Han sees her practice as relating to Zen philosophy and to Qing Dynasty paintings in which multiple perspectives depict a whole universe, both microcosm and macrocosm. We discuss the famous scroll representing an entire town in which every person depicted is doing something different. In ‘Perfect Ending’, a parallel universe of tiny cubicles is filled with girls and consumer products – espresso machines, laptops, mobile phones, shoes and handbags. They strike me as extremely sad. A tiny world appears about to implode under its own pressure. “This is still a male-dominated society,” she says, in response to my query about whether it is more difficult for female artists in China. “But I’m a human being first, then a woman, then an artist.” And, she adds, if you just keep on doing good work, people will have to take notice.

Han Yajuan, Perfect Ending, Oil on canvas. Image courtesy the artist

Bu Hua was born in 1973, graduating from the Institute of Fine Art, Tsinghua University, Beijing, (formerly the Central Academy of Fine Art and Design) in 1995. Coming from a family of artists, with a father who was a distinguished printmaker, she “learned the language of lines” at an early age. Her work is represented in the collection of the White Rabbit Gallery in Sydney.

Bu Hua is best known as one of the pioneers of digital animation in China, discovering the expressive possibilities of Flash software and its potential to convey emotional truths about contemporary life in an immediately engaging and dynamic way. During our conversation she tells me about an artist whose name she cannot remember, discovered in the late 90s at Kassel Documenta, who created wonderful, complex, highly political animations with charcoal drawing. “William Kentridge?” I ask. “Yes, yes, yes!” she exclaims. Seeing his work in Germany was the impetus that made her want to combine drawing, painting and animation. In recent years she has developed a character, a key protagonist in both video and still images, who is based on herself as a child – a defiantly feisty but definitely cute Young Pioneer. She bravely navigates the surreal landscape of the ‘new’ China, encountering strange beasts, mystical forests, hideous pollution and rapacious developers, somehow emerging victorious. She is a girl with ‘swagger’, according to Bu Hua, and a more confident version of the artist herself – a fearless alter ego. In ‘Savage Growth’ she wanted to express this anxiety and fuse western and eastern traditions of art and design. “In modern China, how could you not be influenced by this fusion of West and East, this cultural invasion and ‘soft power’? I am just reflecting this reality,” she says.

Bu Hua, The Water is deep here in Beijing I (2010). Image courtesy the artist.

The girl who skips and jumps through her animations, woodblock prints, paintings and digital images is based on the artist’s memory of herself as a schoolgirl in Beijing in a simpler era. She thinks about herself cycling to school at a time before the recent explosion of wealth and development with a certain degree of nostalgia. Past, present and future collide in the imagined adventures of this ‘Beijing babe’ who functions as a voyeur, a means by which we can see the craziness of the contemporary world.

Bu Hua, AD3012-8,2012, giclee print on paper. Image courtesy the artist.

Like many contemporary Chinese artists, Bu Hua sees no conflict between the disciplines of graphic design, product design and fine art, and she is currently investigating the possibilities of applying her designs to products such as handbags and home-wares. Her professors at Tsinghua were exponents of ‘the new tradition’ in the decorative arts, successful designers and artists, and she is surprised by the idea that some artists might consider this an area to be wary of. Like the apparently hyper-cute and hyper-feminine imagery of Han Yajuan, the works of Bu Hua reveal more than meets the eye. In her still images and animations one has the sense of innocence betrayed, a dystopian fairy tale. “On the surface it’s very cute and very lovely” she says, “but underneath there is anxiety and pressure.” Bu Hua makes her social commentary in an oblique and metaphoric manner. An untitled woodblock print depicts her Young Pioneer reclining on a beach, observing the waves and a setting sun. Initially it appears as a pastiche of 1920s illustration. One suddenly senses the possibility that the ship is sinking and that the plane overhead may be a military aircraft. Portents of disaster are watched by an impassive child who already knows the world is a dangerous place.

Bu Hua, Untitled, 2012, edition:1/1, print on wood block. Image courtesy the artist.

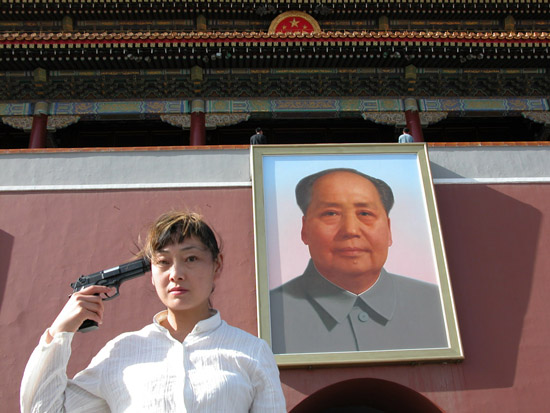

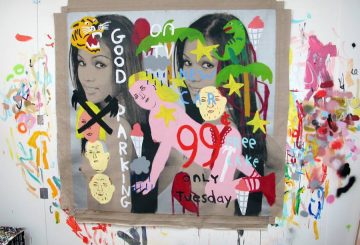

Ma Yanling, born in 1966 in Hubei Province, is best known for her paintings of beautiful women, including Hollywood movie stars and Shanghai divas of the 1930s, as well as public figures such as Mao Zedong’s wife, Jiang Qing. In these works she applies a traditional ink painting technique of extraordinarily fine brush strokes over the entire surface of the image, creating the impression of a screen or net, capturing the woman thus contained. The result is like a Warholian meditation on celebrity and glamour, and indeed, I found some paintings of Marilyn Monroe when I visited the artist’s studio in Songzhuang, Beijing. What is less well-known is that Ma Yanling is a performance artist whose work has focused on uncomfortable ideas about femininity and social control, exemplified by her controversial ‘gun’ series, in which she pointed a realistic replica gun at her own head, in crowded places of national significance.

Ma Yanling ‘Beijing October 11 2007. Photographic documentation of performance, image courtesy the artist.

“Of course, I learned Chinese painting and oil painting at high school, both Chinese and Western techniques, (although) people then paid more attention to Western art. I myself liked Chinese painting more, that was my interest,” she says. She told me of her inspirational journey to Xi’an as a teenager, to see the ancient stone tablets and copy their calligraphy. “Now there are too many tourists so you can no longer get access to those things, but at that time you could get very close and actually touch the tablets – you could really feel this is calligraphy from the Tang Dynasty and you could feel the Tang Dynasty in those words.” Later, she developed a love for cinema, and for photography. “I thought it was more appealing to show life and direct emotions through the lens of the camera,” she says. “What kind of photographs were you making at that time?” I ask. “Ladies. Beautiful ladies!” she says, laughing. With these images she intended, as with her paintings today, to show not only their glamour but hidden beneath that surface beauty the uncomfortable truth that these women are commodities, products, objects of desire. The net of brushed fine lines is like a veil over their faces, hiding their real identity. All people see is the external glamour but, “they are controlled by other people, they don’t have any power over their own lives.”

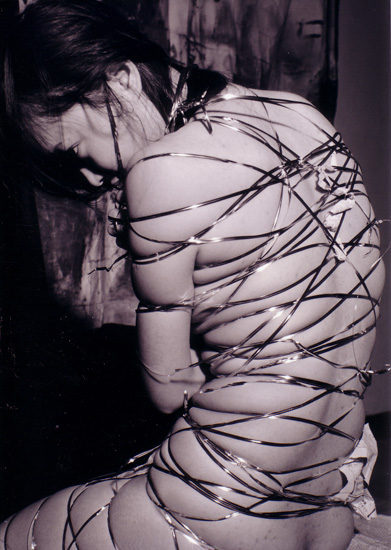

Ma Yanling, ‘Untitled 2004’ photographic documentation of performance, image courtesy the artist

“China is developing too fast, lots of people are getting lost, they don’t know what they want … women are very busy earning money and following fashion. I think it’s quite a pity,” she says. I think of Han Yajuan’s paintings of contemporary ‘material girls’ seeking meaning through their possession of designer brand status symbols. Ma Yanling, as with other artists of her generation, is more interested in how she can reinterpret and reflect upon Chinese tradition. Intriguingly, she then reveals that her apparently disparate practices of creating beautiful ink paintings (themselves, of course, also desirable commodities) and confronting performance works and their documentation, are linked by the concept of ‘Nu Shu’ – a secret language traditionally written only by women in ancient China. This secret script was embroidered into textiles for the dowry of a bride when she left her mother’s home, and was also written in the form of letters which had to be burned after they were read. “Like a Morse Code for women,” says Ma Yanling. Interested in the connections between women across generations, she created a performance with her teenaged daughter in which text was written onto their naked skin, then wiped away. “So it is like you wipe away the language and then you wipe away the possibility to inherit this language.”

In another performance work, the clothes worn by the artist and her daughter are stitched together. “I sew people together, then cut them apart,” she says. It comes as no surprise to discover that she admires Marina Abramovic. And the notion of ‘endurance’ performance is highly appropriate in a Chinese context in which artists are so often reflecting on bitter and tragic events. My young translator later told me that she thought everyone in China was still affected by the Cultural Revolution, which had forever destroyed trust within families, between generations, and created so many terrible secrets that could never be revealed.

Ma Yanling’s series of staged photographs, in which she covertly brought a convincing replica gun into crowded public spaces, including buses, the subway and, with the inevitable result of arrest, Tiananmen Square, evokes all the claustrophobic anxiety that is evident when you scratch just a little beneath the surface in China. From the ‘nu sheng’ seeking an equal partner (or maybe not), to the girls recently pilloried online as sluts after a ‘Vagina Monologues’ performance at Beijing Foreign Languages University, to the young girls strutting the sidewalks of Beijing in tiny shorts and high-heeled boots, femininity is decidedly on the agenda. Ma Yanling said, “Young women have more power now.” As with everything else in this new ‘Chinese Dream’, however, the processes of change and transformation continue.