Our first guest blog this week comes not from a fellow blogger but from Ian Houston, an actual reader of The Art Life. Mr. Houston writes from New York on the exhibition “Meet the Artists: Collaborative Works by Jake Paul George and Dinos” at Dietch Projects in Soho, New York, New York, USA.

At the very least you’d expect a few thrills from an exhibition of collaborative works by Jake and Dinos Chapman, George Condo and Paul McCarthy. Paul Mc Carthy and the Chapman brothers are responsible for some of the most confronting if not shocking art of the last few decades whilst George Condo has been knocking off gently offensive pop art since the seventies. Sydney-siders can avail themselves of Paul McCarthy’s deliciously obscure and decidedly gross Pop Art at AGNSW, while the Chapmans and their predilection for the intersection of the grotesque and the erotic have become staples of the tabloid’s view of contemporary Brit art. So it comes as something of a surprise to see just how painterly, witty and subdued this exhibition is.

The show consists of an installation formed from a series of canvases and lithographs spread across two rooms on the Grand street branch of the Dieter projects galleries. Begun last year, the collaboration was conducted sequentially, each artist working in isolation and then passing the work on to the next collaborator. Four large canvases, four small canvases and four etching plates were delivered to the homes of the artists. Two in London, one in New York and one in Los Angeles and then rotated until the works were deemed “finished,” though abandoned is perhaps a more appropriate understanding given the nature of the method. In a certain regard this echoes the Surrealist literary technique used in the exquisite corpse where the artists don’t collaborate in the sense of collective deliberation and action, but rather paint on, over, through and around the last artist’s contribution with out regard for their intentions for the work. Indeed this idea of separate action was so important to the artists that the Chapman brothers had a brick wall built in their studio so they could provide their contributions in private from each other.

Installation view, Meet the Artists, Collaboration work by Jake & Dinos Chapman, George Condo and Paul McCarthy.

Photo credit: Tom Powel Imaging.

So if this was a game then for the artists, it also becomes one for the viewer, who becomes enmeshed in identifying the separate strands of the artist’s work, and then imagining how the collaboration has proceeded. This process engages the viewer in an act of unstitching and gluing where the work’s cohesion goes from suspect to genius in a few slippery moments. I found this to be the most intriguing aspect of the show as much for what it reveals about method as it does about the romantic identification of the artist with the heroic notion of the artistic “I”.

For instance, it quickly becomes obvious, that cooperation is not necessarily central to the process. It would appear that the artists worked against each other as much as with. One of the four large canvases (untitled) that form the installation has been cut into tiny squares and rearranged, a la Rosalie Gascoigne, though I hasten to add, not to achieve the elegiac modernism of her landscapes, but rather so the protagonist could spell the words Evil Cunt. It is tempting to imagine that this was both an act of sabotage and a proclamation of genius, allowing this artist the final say in the work and reducing the influence of the others to mere grist for the mill of his invention. Though such thoughts are speculation it is exactly this kind of conjecture that remains one of the show’s most satisfying elements.

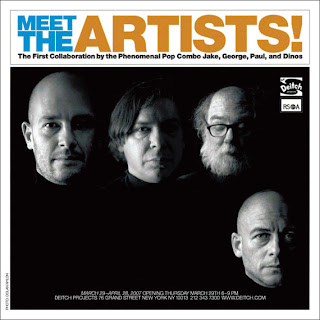

Jake and Dinos Chapman, George Condo and Paul McCarthy,

George, Dinos, Jake, Paul (portrait), 2006.

Hand colored etching, 136 x 100 cm, Edition of 8.

The other three large canvases involve the usual cast of debauched cartoon characters, defaced, defacing and off their faces. There are plenty of cocks, tits, pussy and needless to say enough blood to satisfy the basest of instincts, as well as a surprisingly large number of references to the act of painting itself, with one canvas featuring a painting bumble bee and another, a bloodied but still drawing, gloved mouse hand. This last figure is painted across the exterior of a box that protrudes from the surface of the canvas. On the box are pinned previous works of “the artist” while a “paint rag” on which some waxy pvc has been dribbled, has been clipped to its edge. Intriguingly the centre of the box is cut away to reveal a small section of what looks to be a highly glazed, landscape painting, with darkly luscious storm swept hills. The box is hinged and perhaps, if the room was unattended for a moment, you would be able open it and find an answer to the mysteries of the painting. Though I doubt it very much.

One of the smaller canvases riffs on the structural elements of canvas painting with the top left corner of the canvas ripped from its stretcher and a complex cartoonish structure of wooden beams nailed haphazardly to the front in a jumbled echo of the stretcher bars. Yet despite the anarchic and confrontational nature of the work it still maintains a sense of resolution. Indeed all of the works have a certain harmony and resolve that seems to have stemmed from the intensity of the collaboration. One would imagine that for the process to work the artists would have had to both embrace chaos and the sense of abandonment that comes from having aspects of the work out of their hands at the same moment as needing to bring the wildly disparate elements into some kind of relation. It is this enjambment of disparity and harmony that gives these works their depth.

It’s interesting then to reflect on how these collaborators – by giving themselves over to chance, instinct and the automatic – seem to have rekindled a sense of artistry that is guided less by the nihilism of contemporary axioms and more by the demands of the finished picture. Perhaps that is why they have chosen to depict themselves on the cover of the show’s catalogue in a parody of the 1963 Beatle’s album Meet the Beatles. Photographed in black and white half lit and wearing polo necks its heartwarmingly nostalgic if not a little unnerving to see the purveyors of dildo nosed child mannequins so sweetly rendered, even if Paul McCarthy’s eyes remain closed. For me it was a way of saying paintings are like pop songs, no matter how much you hate them, you’re always going to end up singing along.