From our London correspondent…

It had to happen. Not content with the good life here, one recent recruit to TEAM Art Life has decamped to London, dusting off that British passport – now a ticket to the whole of the EU (we’ll get on to that later)– to explore ye olde England, and life in the big metropolis of London. Land of frosty smiles, addresses on the Monopoly board, the tube and double-decker buses, there is more to the art life of the Greater City of London than the annual Frieze Art Fair. As our correspondent reveals, the winter months are packed with slow-burners.

Yes, to those of you still at the beach, here it feels as if we have just come out of the mini ice age of Christmas and New Year. Things are a little slow to get going and, like the weather, appropriate for the winter-gloaming of short cold days and festive lights. A lot of the galleries seem to be shrouded in an extra cloak of winter darkness to maximize the projected light effects of what seems to be a seasonally affected, unofficial festival of artists doing film and video summed up by the fantastic program ICO Essentials: The Secret Masterpieces of Cinema at Tate Modern 18–21 January (see www.icoessentials.org.uk for film list and UK tour details).

This 6-part series of curated sessions on the themes of Dreams, Pop, Expression, Play, Modernity, Protest, was a timely reminder that artists – or those whom we would call artists now – were up there from the start working tricks with the medium, as fantastic as it is mundane, ripe for eaking out more radical, interrogative social objectives, as well as those moments of pure beauty and silliness. The ever-present flicker, flicker, pan shots and montagist madness are all a factor in this medium that crosses endurance with enchantment. Without going to the details here, it is worth being reminded of what has already been done before knuckling down to the more current agendas. Maybe they haven’t changed that much. On the one side you have the technology, and its presentation requirements, and all the various opportunities to deconstruct the apparatus. That this approach, limited to the purely formalist objectives, has a limited life span is however amply demonstrated by the recent reappraisal of Anthony McCall in his retrospective at The Serpentine.

Installation view. Solid light installation, 32-minute cycle in two parts

Computer, QuickTime movie file, two video projectors, two haze machines

Dimensions variable

Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery, New York

In this exhibition, you could be excused from walking rather quickly through the first room featuring McCall’s work from the 1970s: the somewhat quaint film and slide show documentation of early performance works with men in white suits supervising grid-like interventions in the landscape with fires and flares and white squares, presented alongside other process-driven exercises on paper. It is also hard to get too excited about his abstract experiments with 16 mm film projections as a continuation of the form. What most people were clearly into was the spectacle of the large moving light sculptures, replacing their earlier incarnation as 16mm film projections with digital video on a continuous programmed loop made visible through the accompanying haze of smoke machines that cast a strange oily palpable body to the travelling passage of light. Replacing the early descriptive titles such as Line Describing a Cone with the more participatory language of Between You and I, it was indeed like being in a fun fair, hooting at your friends across the room. All the same, there is something slightly forced about this trippy new age enthusiasm, like taking Ecstacy on the dance floor, maybe too much of a cheap-thrill and chemically induced bonhomie although fun while it lasts. What this work really needs to update its somewhat laboured architectonics is more of the human element. McCall could collaborate with Callum Morton on creating a smoke-filled cinema completed with the light effects and dramatic film noir soundtrack. Or, like Olafur Eliasson’s mesmerizing golden sun that filled the space of the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern in 2003, create artificial environments that help prevent getting SAD. Alternatively, he could rent out a stadium and do something with performers or footballers . . .hhmm, it has, alas, all been done before.

Installation view at Sadie Coles.

Just a short trip across Hyde Park to Sadie Coles’ new space in South Audley Street, Mayfair, these overblown thoughts and expectations are happily released by Jim Lambie’s obscurely modest reflections on the arc of light in a kind of Lucio Fontana-esque puncturing of the star-studded night created by what looked to me like invisible hands carrying sparklers, intended to represent a ‘metronome for our darker hours’. Artists working with a video camera can of course be wonderfully simplistic if they want to. Last week’s feature of this rolling month-long programme at Sadie Coles was the no less mundane but strangely satisfying Sausage Film (1990)by Sarah Lucas skinning, slicing and eating a sausage and a banana, invoking this artists well-known mocking fetish for foody images that represent genitalia. This also brings to mind the slapstick gore of Sacrificial Mutilation And Death In Modern Art (1999) by the Chapman brothers that featured in the ICO Essentials film program for ‘Play’, in which a red-paint filled glove enacts the various accidents that have befallen famous artists filmed using the constructive detritus of the studio space, and the kind of edgy explosions, making-do with the materials at hand to construct the narrative, that Fischli & Weiss and Tony Oursler make such a great go of.

Walking further south through Mayfair towards Hauser & Wirth, Piccadilly, more in this vein is on offer in the current show of work by Roman Signer. This does I suppose stretch the boundaries of what might constitute an artists’ film or of ‘working with the moving image’ but it is clearly central to an artist like Signer that his sculptural actions caught on camera are distributed for perpetuity through the video format, so perfect as they are for YouTube. In his current show, a handle-less lawnmower let loose on the crowd of viewers and chairs plays the classic, irritating, ankle biter. A very cute machine it is too. On show are a number of videos including, in the bank vault gallery space downstairs, Old Shatterhand (2007). In this work the geriatric shaking hand of the artist trying to shoot at a target, as the slow pan reveals, is the result of the in-built handicap of being tied up to the stomach-reducing belt of an exercise machine. Helicopter on Shelf (1998) is another great example, showing a radio-controlled helicopter that flies off when its landing pad falls over the edge of a waterfall, hovering about like a dragonfly before re-alighting when the plank resurfaces downstream. A regular Buster Keaton, with overtones of those clumsy strings attached to the puppets in The Thunderbirds, I’d hazard a guess that this is also where Tony Schwensen got some of his inspiration from . .

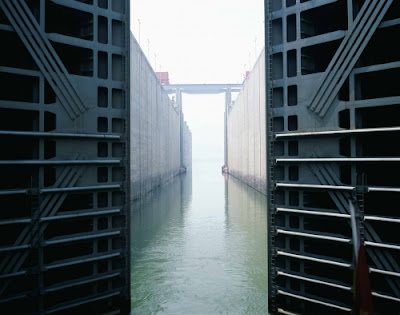

Catherine Yass, Lock (filmstill), 2006.

Two simultaneous projections of 16mm film transferred to

HD-MPEG digital files, with sound, 9 Mins 44 Secs.

OK, we at The Art Life do like the fun stuff. Clearly, for many artists more fully invested in high production values and multi-format presentation screens within the gallery context, video like the architecture it inhabits lends itself to the bigger picture. This desire for more extreme pursuits and exotic locations is a feature of the work of Catherine Yass and Darren Almond, also currently on show in London. Yass’s film Lock (2006) at the Alison Jacques Gallery is impressive in representing the ascending and descending view from a crane on top of a barge to represent the shifting into gear of the industrial machinery required for a freight ship to pass through an enormous lock at the entrance to The Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River, China. Scale is one thing, as is the sound of the passage through these fortress-style caverns, in which the rise and fall of the water level, as one door opens and another closes, it is implied, also serves to represent the vast changes occurring across China itself. The view of this bleak stretch of water and the monoliths rising out of this once free-flowing river, shrouding the loss of historic cultural sites, land, livelihoods, ecosystems etc. is presented to us here as the brave new world of China’s modernization. As united nations as this sounds, the physical presence of this massive shift is real enough, at least in terms of conveying the physical experience of the built structures that define power as continuations on the theme of her previous films, Descent (2002) taken of building sites at London’s Canary Wharf and Wall (2004) tracing the barrier that divides Jewish and Arab territories in Jerusalem.

Darren Almond, In The Between (Landscape), 2006.

3 Screen projection on high definition video with sound.

Duration 14 minutes.

Darren Almond, the subject of an exhibition at The Parasol Unit and White Cube, Hoxton Square, demonstrates a similar scale of ambition and preoccupation with geo-politics in his multi-screen installations at The Parasol Unit. The feature work of this exhibition In The Between (2006) shot in China and Tibet, shows a central screen of monks in their quarters, flanked on either side by images of the landscape taken from and of the train (the Qinghai-Tibet railway) built by the Chinese as part of their incursion into Tibet, making it also clearly possible for foreign visitors (like Almond) to visit this otherwise remote and isolated part of the world. Shown in tandem with his most recent video Bearing (2007), a single-screen projection highlighting the daily routine of workers in an Indonesian sulphur mine, Almond’s intention to highlight socio-political injustices while reveling in the sublime aesthetics of landscapes so evocatively colour-coded is nevertheless hard to stomach. This latest work as part of an overall schema that privileges this seeking out of extreme landscapes and exploitative conditions, as in the accompanying series of photographs of the snow-clad, dead forests of post-industrial Siberia, requires a significant leap of faith. These images of poisoned, suffering workers in the yellow landscape, and strangely disempowered resident monks with their red robes and regalia, rather frustratingly difficult to see in the gloom of their quarters, presented alongside the coolly elegant, pared down spindly forests blanketed in white provides a kind of strangely convenient trilogy of effects. But unlike the dramatized poetics of director Krzysztof Kie?lowskie’s Three Colours: Blue, this motivation to colonise the world with a paintbox seems oddly inconsistent and rather like a freak show. What Almond excels in is creating beautiful images, there is no denying that. There must however be a better way of conveying their message.

Willie Doherty, Ghost Story, 2007 (video still).

The concept of the artist filmmaker is a hard one to live up to if you’re not Julian Schnabel. Something of this dilemma was revealed by the artist Willie Doherty in discussion with Tim Marlow at a recent Artprojx screening of Ghost Story (2007), Doherty’s film commissioned for and originally shown in the Northern Irish Pavilion of the Venice Biennale. As Doherty was only too happy to admit, in professional terms his approach was all the wrong way around, starting out with the location, and followed by the rest, presumably the script, the scenography, the whole complicated business carried out by any able film producer and production team.

For Doherty the important thing was capturing the experience of walking along the road, not just any road but this road, on the outskirts of his home town of Derry, an important site of much of the violent events that he heard about and experienced with some degree of proximity to the violent events during the long history of The Troubles. Such sensitivities, or what we in the art world might consider to be the prevailing ‘authenticity’ would not normally obtrude on the proper processes of finding the appropriately filmic location that works best cinematically. Is this a documentary or is it fiction it might do well to ask. Taking on board the personal voice, it felt like the film that Doherty spoke about was a different film to the one he ended up with. Yes, he got the road, and the monologue as script. His words were certainly beautifully articulated by the actor Stephen Rea. But why, for instance, this smooth dolly riding over the furrows of the dirt road, when as a walker you would be lower , closer to the ground and bumping along, switching angles and viewpoints, looking about you? Nor it appears was he quite able to resist the standard perfections of the jump cut imposed to break up the monotony of his digression on the 7-minute shot along this road leading up to its mesmerizing vortex, that ended with a close-up of woman’s face as she stood silently under a tree, barely visible until well into the shot. The two other incidents – the threatening figure of a youth waiting under the flyover and the car that seemed to appear from nowhere with an unseen driver – although hauntingly and beautifully captured as scenes also seemed unnecessary as they were sufficient illuminating in the story as told. In short, I couldn’t help feeling, Doherty would have been better of following his own plodding artists’ (as opposed to filmmaker’s) methodology. For all these reasons it is timely that a retrospective survey accompanying the London screening of Ghost Story at Matt’s Gallery will be accompanied by a rolling program of his earlier films, scheduled over the coming weeks.