For her latest exhibition Cash Brown has created a series of paintings based on Gustav Courbet‘s infamous Origin Of The World. On show until April 22 at Robin Gibson Gallery, this 142 year old image – and Brown’s treatment of it – is again causing a stir.

For those who may not know your work, what have you been doing over the last few years?

Cash Brown: Heaps. Despite losing the use of my right arm (I am right handed) for most of 2004/05, which was a real pain as I had just graduated as a mature age student from the National Art School, I managed to involve myself in 46 group shows, two solo shows and appearances in the Moran, Salon de Refuses, Portia Geach etc to name a few as well as a couple of residencies, a few months in Europe, a painful divorce, doing lots of charity work, losing my house and consequently moving house several times. Some of the group shows were really time consuming, expensive and great to work on, its a bugger that not many people seem to visit galleries other than the pissup on opening night.

Cash Brown, George, 2008.

Oil on canvas, 50×60cms. Courtesy the artist.

You’ve had your work hung in the Sulman at the Art Gallery of NSW recently and worked in collaboration on two shows with Adam Cullen. How does this show with Robin Gibson connect to those projects?

CB: Hmmm. I’m not sure I would call one painting in the Sulman a project, but it was a picture of me. The collaborations with Cullen also included a performance at the MCA which may be even more difficult to relate than the two MOP. The MCA work was about censorship, freedom of speech and context of art and literature. The works with Cullen were interesting for us to work on in that they didn’t involve painting. We both get sick of making paintings but share a great love of the natural world, playing with stuff, the absurd, the kitsch and the ridiculous. Painting obviously isn’t always the most appropriate means of communication and the particular ideas we were addressing or attempting to communicate manifested themselves in those collaborations, which used lots of different mediums, had a great sense of play yet maintained a rigorous conceptual ground. The Robin Gibson show for me is not much different in that it has a core set of ideas played out in a variety of ways using a variety of means. It’s pretty playful too, but I did this work all by myself.

What drew you to Courbet’s Origin of the World as the subject of this show?

CB: I have been thinking a lot about the concept of originality and the derivative nature of so much contemporary artwork, especially since attending my first Biennale in Venice last year as well as the rest of the “Grand Tour” and heaps of collateral events. This led me to think of the beginning of Modernism. Origin, original, beginning, it all seemed a bit obvious and almost naff but I liked that about it. The idea of revisiting the image became even stronger after reading Juan Davila‘s thoughts on the work and seeing his versions. He always gets me thinking actually and he kind of reinforced the relevance not only of visiting that image, but also of appropriating imagery from the past and present and referencing other artists. And, it was painted exactly 100 years before I was born. And, I think it is an incredibly beautiful painting. I wish I could paint like that. The fact that it still makes people avert their eyes when they see it at the D’Orsay is pretty interesting too. I wanted to see what would happen if I fucked with it a bit, but not in a vulgar way, I am not really interested in repulsing people on purpose.

Cash Brown, A Mutt, 2008.

Oil on canvas, 50×60cms. Courtesy the artist.

The painting is claimed to being the cause in the end of the friendship of Courbet and Whistler as it is purported to be of their mutual lover Joanna Heffernan. Does the history of this painting have any bearing on your choice of Origin of The World for your series of paintings?

CB: No

Courbet’s painting was commissioned by a Turkish-Egyptian diplomat named Khalil-Bey for a collection that was apparently a “celebration of the female body”. After that the painting went through various owners including Jacques Lacan but wasn’t shown again publicly until 1995. It has been a veiled image, known to art history, yet lost to public view. In your show you’re revealing the same image over and over, each time with a slightly different shock. What were your thoughts on that process?

CB: I cant see why this image has been so censored when we have images and effigies of a flayed Jewish guy cruelly nailed to a cross everywhere, that’s really disturbing. Maybe its because its been seen so many times and is part of the western landscape that it no longer has the capacity to shock. Sure we don’t see images of the vagina every day, but half the population has one, everybody has seen one, touched one, come out of one, its not that big a deal for me but maybe underneath it all I think repetition is a way of making things “acceptable”. During the process I actually got really stuck a few times, wondering if it was like a one liner being told over and over again, and painting the same image over and over took a lot of self discipline. The serious questioning and self doubt that crept in was tempered by the desire to make work that goes beyond a gag and to make something relevant. Art history provides all of the nutrition because all of the big ideas have been covered, over and over again, yet we still keep finding new ways to make work. Using shock, humour etc is one way of getting the viewers attention, but it also keeps me interested in making the work in the first place. Clement Greenberg once said something like ” aesthetics were of as much interest to artists as ornithology is to birds “. I can only agree with this statement as far as birds have no consciousness so of course he is correct, I however am very interested in aesthetics and this body of work is an aesthetic investigation. I would like to take it further.

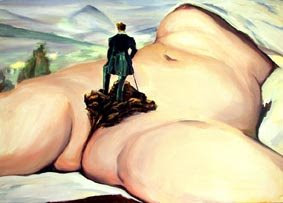

Cash Brown, Contemplating the sublime, 2008.

Oil on canvas, 50×60cms. Courtesy the artist.

What do you suppose the image means in a contemporary setting?

CB: I don’t think the meaning can change really. It’s just a cunt. It is pretty obvious what it is about. The way people react to it though is very interesting, I cant believe they still get upset or embarrassed, that hasn’t changed. By putting eyes and a nose on it for example, it seemed to have the effect of immediately sanitising the image. Suddenly one could look at it openly and snigger without fear of being a bit of a perve. By scaling it up to 12 times its original size, it became a kind of landscape, too big for intimacy and similarly sanitised. I would like to put it in a really contemporary setting, like an Ikea store or as a mural on the side of a maternity hospital, on a billboard on the M4 and projected onto the Opera House.

You’ve used this image in a rather funny way, putting references to various art historical images…

CB: I am a bit of a history nerd and thought if I was going to appropriate one image then why not all of the references? That actually was pretty hard so I referenced myself a couple of times.

Have you had any problems promoting this show using these images?

CB: Both Robin Gibson and I had numerous requests to be removed immediately from our emailing lists. Some people thought it was a very rude April fools day joke and were not impressed. The show opened April 1. A few people phoned the gallery and complained about the explicit nature of the invitation and one woman rang threatening to sue us for sending pornographic material through the post, claiming her daughter had opened the mail and was traumatised and that she would be reporting us to the relevant authorities. This has to be a joke though so very funny whoever did it. I am sure it won’t get a centre spread in Spectrum nor will it be likely to adorn the cover of Australian Art Collector. I actually honestly didn’t think it would even raise an eyebrow, but that goes to show you how naive I really am, assuming everyone knows their art history, silly me. I think I should have made a T-shirt with the image on the front and back and worn it all week around Darlinghurst where I work, that would be good publicity. The funny thing is how you can see some people trying to be cool about it and not admitting that they are uncomfortable because they know its art and they know its old news. I think its great that art can still affect people.

Cash Brown, Study For Durer’s Pubic Hare, 2008.

Ink, conte, gouache and watercolour on arches paper, 13x17cm.

Courtesy the artist.

Why is the title of your show “Appropriate”?

CB: Well it is, isn’t it?

We took the title to mean something in relation to the appropriateness of showing such an image, but perhaps all the definitions of the word are relevant. You say that you don’t think the meaning changes but doesn’t the context change? You’d be getting people who are shocked by the “inappropriateness” of displaying an image like this, but to put the question another way, you’re a contemporary artist, and a woman, does that have any bearing on your choice of appropriating this image for your own purposes?

CB: Of course the context changes,and times have changed, but I wonder how much the viewer really changes. That’s the point. The shocked people are really funny, I think that comes from a lack of education (they think it is an “original” image) and I find it impossible to think this image could be remotely offensive. Maybe they are shocked for other reasons, I am not a psychologist. But I honestly didn’t think it would get the reactions it has received, not now, in 2008. Some people calm down a bit after reading the catalogue essay which is written by Cullen and explains it all rather well. Appropriating this image, changing its context and doing it as a woman are all rolled into one but I seriously wanted to avoid making any feminist statements. I think a male artist could have made this work but I wonder if people would view it the same way. I have tried really hard to find a similarly important image of male genitalia but there isn’t one I am aware of, besides, the relevance of the image goes beyond its content, the cropping for example was a great early Modernist innovation and dicks and balls aren’t quite as relevant (or attractive). Hardly anyone is painting nudes anymore, they have become kitsch, Lucian Freud isn’t the flavour of the decade and yet we see nudity or near nudity and sexually explicit imagery on a daily basis. Some of my past work has dealt with this, and censorship, but no one wanted to show it, (apparently I was labelled a sexist by someone who wasn’t aware of my gender) and I think its really amazing that if this image was not viewed in the safety of the fine art context, it would be viewed as pornographic.