From Isobel Johnston…

The 16th Biennale of Sydney opens in a just a few weeks ’Revolutions – forms that turn’, connecting past and present work.

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev will bring together ‘constellations’ and encounters rather than juxtapositions- in clusters of artists. A much more ‘organic’ rather than imposed curatorship is sought by Christov-Bakargiev so this framework does not to impose itself but can be likened to a well staged dinner party which brings together the right mix of guests who in turn fire off each other to do the rest. This my understanding of the analogy given by Christov-Bakargiev at at the Art of The Curator forum recently staged at the Goethe Institute on May 12.

Do not ride bikes at night. Always wear a helmet.

It’s really also about the influence on both past and present some artists have had and where other artists have taken these influences into their own practice: to bounce off, to extend, to challenge or to dialogue. For this Biennale these encounters involve bringing together the work of older artists that have had an impact of their own contemporaries as well as on the present. Some of these artists are less well known and were not acknowledged until recently and yet their work has had this impact across both past and present. These pre-runners are joined to both their own contemporaries and to a new generation of artists whose work crosses similar terrain as constellations.

Christov-Bakargiev identifies and has established a methodology of re- presenting past and present as simultaneously contemporary – that art works of the past not only have a resonance in the present, but that they exist in the mind of a viewer who is experiencing them for the first time as contemporary [Wulf Herzogenrath at the Goethe Institute] and are melded into the fabric of that viewer’s here and now. The revolution might also be the acknowledgment of the art historical instability which has exerted itself on the cannons and perception of art history for the last four decades, as attested to in Christov-Bakargiev’s own theoretical interests and position firstly in feminism and then with arte povera. Centres no longer hold and we are all spinning into the widening gyre [ …with apologies to WB Yeats]. A different take on this could also be in two past Biennale’s of Sydney: The Boundary Rider Biennale and Rene Block’s Readymade Boomerang.

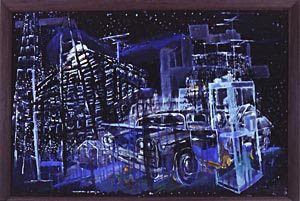

Frank Littler, Sunrise under car No. 3, 2005.

Acrylic and oil on hardboard, 68x98cm.

It’s 40 years since May ’68 and the possibilities sought by students and workers of Paris. The conflagration of change that caught on internationally and teetered with the real possibility of change works as a perfect example of this coexistence of history and its contemporaneous other. Revolutions – forms that engage the stories, narratives and fictions that are the shifting sands of historical and contemporary truths. The connections also cut across a piece I was writing about Frank Littler’s work and seemed offer another kind of turning.

Stories is a good title for Frank Litter’s exhibition opening in Melbourne in June in a couple of weeks and overlaps the 16th Biennale of Sydney. The paintings in this show initially look quite disparate – heads, buildings, maps, caves and the aquarium but gradually the viewer becomes aware they are linked by Littler’s use of various formal and perceptual screens.

Through these screens Littler invites us into a space which lies beyond the surface of the picture plane, often an enclosed cave- like space where the visual action is taking place.. These screens are not constrained to the surface but travel through the work to intersect as much as they overlay the image. It is these points of disjuncture and rupture that draw attention to our own ‘reading’ and our own ‘seeing’ of the painting before us.

We bring what we know of the world to our reading of a painting- it happens in a moment and in the completeness of seeing but it also happens slowly and over much a longer space of time. There is the experiential and there is an analytical reading. Litter’s painting and images do something strange in that they manage to sandwich both ways of reading together and fix them in the same inseparable moment.

Littler’s use of the picture plane is at the very heart of his work – work that is about the actual language of paint and at the same time acknowledge that the works must reflect the artists own experience, interests, views and concerns. These may not be in the forefront of the artist’s mind while painting but instead pop up in the work less consciously than that.

The title is also on the other hand a bit of a ruse. These paintings are not didactic, the stories they tell are multi-layered, quirky and incomplete. You take them in as a whole, the surface, the screen, the cave like centre, the various actions the ambiguous use of space that blur the paint and its depicted forms but as to what to ‘read’ that remains open-ended.

If I could bring Littler’s work together with Max Beckman, Giorgio de Chirico and John Heartfield (artists he sites as makers of images that resonate) and I’d also add Phillip Guston and Mitch Cairns to the mix – I think Christov-Bakargiev would have another constellation. And I feel she would like the idea that just as the artists in the show dialogue, that the 16th Biennale’s dialogue extends beyond it’s own parameters to resonate; revolving to reflect on the other exhibitions and artists work just as Frank Littler’s work goes out beyond the parameters of Melbourne’s Place Gallery.