Handpicked content for your reading pleasure and edification:

“What’s left of Saddam Hussein’s showcase collection of 20th-century Iraqi art is crammed into three dingy galleries of a formerly grand museum on Haifa Street here. The rest of the building once known as the Center for Contemporary Art has become a warren of offices and cubicles fortified by bricks, barbed wire and sandbags and closed to the public. Hundreds of works are packed away in a hot, dusty storeroom, tended to by a doting but frustrated staff. Many of the paintings there are damaged. All are withering from dangerous conditions and haphazard storage, from the heat and Iraq’s official indifference to an important if lesser-known part of its artistic heritage. Such is the state of Iraq’s modern art collection, renamed the National Museum of Modern Art in 2006 yet still an institution that exists mostly as an idea. That it exists at all is owed largely to the efforts of a group of officials, curators and artists who have struggled through years of war to rebuild what was even under dictatorship a record of an artistic awakening that produced a century’s worth of painting and sculpture in modernist styles, borrowed from international movements but filtered through Iraqi and Arabic sensibilities…”

Read More: Iraq’s Modern Art Collection, Waiting to Re-emerge

“Harvey Pekar, who turned his unglamorous, blue collar life into a cult series of comic book stories, has died at the age of 70 in Cleveland, Ohio, police said. Pekar, whose American Splendor was the basis for a critically acclaimed 2003 movie, was found dead early Monday at his home, Cleveland Heights police Captain Michael Cannon told AFP. The cause of death was not immediately known. “The coroner’s office is going to be issuing a report. There was nothing suspicious,” Cannon said. Pekar’s comic books were based on his life as a hospital file clerk, filled with insights about human nature and the surprising complications of an outwardly humdrum existence. After building a devoted fan base, Pekar went on to be accepted by the mainstream comics world. The film American Splendor, honoured with the top dramatic award at the 2003 Sundance Film Festival, drew favourable comparisons with the early work of Woody Allen…”

“Victoria Miro is the quiet woman of British art: visionary but not in the grandstanding way of some of her more famous counterparts. Or, as Grayson Perry puts it, “not tainted with the hoo-ha and the celebrity glitz that, at the height of the YBA era, almost consumed the art”. Her gallery began life in 1985 in 750 sq ft of space on Cork Street; it now takes up 17,000 sq ft on the edge of Hoxton: a metaphor, then, for the trajectory of British art over the last three decades. She is currently celebrating, albeit in a quiet way, her gallery’s 25th – and her own 65th – birthday. In acknowledgement of these landmarks, she has decided for the first time to give an in-depth interview. First, though, she insists on walking me around her latest exhibition, In the Company of Alice, a wonderful group show that features portraits by the late figurative painter Alice Neel, and responses to her work by the likes of Chris Ofili, Doig, Chantal Joffe, Marlene Dumas and Elizabeth Peyton. Although she died 26 years ago, Alice Neel, who has become something of a feminist icon because of her bohemian lifestyle and her unflinching dedication to her work, is Miro’s current passion. “We put on the first European show of her work in 2004,” she says, proudly, “and, in the six years since, she has come in from the cold.”

Read More: Victoria Miro, queen of arts

“Music is a collection of notes arranged in a particular order and heard in a particular context (thus a person noisily unwrapping a piece of candy can be music, but unwrapping candy during a Mozart concert is merely noise). Christian Marclay makes art in much the same way that one might compose music — by arranging things, often sounds, in a particular order and placing them in a specific context, a gallery, museum, or other space devoted to perceiving the arrangements of things. For the last 15 years or so, he has been composing what he calls “graphic scores,” arrangements of musical notations found on objects like clothing, record album covers, photographs, and boxes. “Christian Marclay: Festival,” an exhibition and series of performances at the Whitney through September 26, focuses on the scores, both in performance and as visual artifacts, while also presenting objects to be played by musicians, drawings, sculptural pieces, videos, and ephemera. For a visitor, this wonderfully challenging show is not always a melodious experience. Confronted with, say, the thirty album covers in Covers (2007-2010), one wonders what to make of them. Eventually it becomes clear that Marclay has chosen the group because each cover has some musical notation printed on it: the work consists of ordering the albums and then playing the notes as a single piece. Similarly, Box Set (2008–10) requires a musician to play the notes on a group of found boxes, which he must first place inside one another Russian-doll style in whatever order he chooses. As one peruses these ingenious scores at the Whitney, squeaks, horn blasts, and other notes tumble through the space as musicians interpret the music they suggest. Of course, most of the notations Marclay has gathered were not made by composers but by graphic designers so the resulting scores can be discordant…”

Read more: Christian Marclay: “Festival” Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

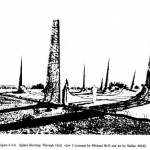

“A larger question concerns our scientific knowledge: is our representation of the natural world universal? Throughout the half-century of SETI, Cocconi, Morrison, Drake and their followers have argued over which regions of the electromagnetic spectrum it would be most ‘rational’ to target for a search. They have based their arguments on naturally occurring processes like the 21-centimetre hydrogen line or similar emissions from other constituents of water molecules. But who is to say that other advanced civilisations – even if they pursue something like scientific investigation – would carve up the confusion of nature in the same way as we do? We now think in terms of atoms, electrons, quantum transitions and electromagnetic waves, but are those the only ways of making sense of physical phenomena? Can the intellectual history of Western science really be a universal phenomenon, with the current state of our science being a fixed point in the evolution of intelligence everywhere in the cosmos? […] SETI might indeed make its greatest contribution in the nuclear arena. Some of the most hazardous by-products of the nuclear age, including isotopes of plutonium, have half-lives of hundreds of thousands of years. One challenge is to find places on Earth that are likely to remain geologically stable over such a time-scale, where such waste can be buried. A second challenge is to design symbols to warn our descendants, 300,000 years from now, not to go digging in these areas. As the historian Peter Galison has been documenting, the US nuclear agencies have sought the wisdom of diverse experts – linguists, anthropologists, sculptors – to imagine how we might plausibly communicate with terrestrial beings in the impossibly distant future. After all, the Latin alphabet dates back a mere 2600 years; only hubris could lead us to imagine that familiar modes of communication will be recognisable in the year 300,000 AD. Alongside linguists and artists, nuclear bureaucrats have also enlisted experts in SETI. Struggling to communicate with our future selves calls for the same kind of radical imagination that SETI requires. Both efforts criss-cross the boundaries between disciplines; both require experts to project from what we know about our own civilisation to facilitate communication with some distant other. They are mirror images, twin children of the nuclear age.”

Read More: David Kaiser: Diary LRB