Culture smashes together in Smash Palace, reports Luise Guest…

Smash (verb): shatter – break – crush – crash – dash – demolish – crack

Smash (noun): crash – clash – collision

Intrigued by the title for this new show of contemporary Chinese art at the White Rabbit Gallery, I wondered at first what curatorial narrative could possibly connect such diverse works. From artists working with oil paint applied with a cake decorator’s nozzle, to drawings made with biro, to collections of miniaturised possessions, to mechanised French railway tickets, to sculptures made with a 3D laser printer the works illustrate the diversity and in many cases the technical virtuosity and conceptual complexity of contemporary art in the People’s Republic and Taiwan.

Seen together they tell a story of today’s China which ironically echoes Mao Zedong’s exhortation to “Smash the Four Olds” – customs, culture, habits and ideas. The “smashing” taking place today relates to the dramatic and fast-paced change being wrought by global capital and modernisation. This has resulted in mega-cities housing upwards of 20 million citizens; the social upheaval, barely contained and controlled, of the largest migration in history of workers from rural villages to the factory towns of southern China; and the transformative possibilities of communications technology as people begin to demand greater freedoms. The genie is well and truly out of the bottle in this last instance – a news story this week reported Chinese netizens’ responses to a People’s Daily story listing the names of the 2987 ‘representatives’ attending the National People’s Congress. Howls of fury, savage mockery, cynicism and disenchantment erupted on Sina Weibo, the Chinese micro-blogging site which now has twice as many users as Twitter. Most of the comments were variations on “Who the hell are these people and how did they come out of nowhere to represent me?” Others wondered how long it would take for corruption scandals to unseat them, while @?? tweeted, “I refuse to be represented. In this information age, I speak for myself.” This prevailing sense of unease and anxiety at the dark side of the increasing wealth and power of China is expressed by many of the artists in this exhibition.

Wang Guofeng, Ideality No 1, 2006, photograph, 57.5 x 251 cm, image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery

On the ground floor Bai Yiluo’s 2008 ‘Recycling’, an enormous fibreglass human heart tied onto the back of a tricycle of the kind used to transport materials and recycled paper in Chinese cities, suggests the ways that our human needs for love and kindness are disposable in the rush to acquire material wealth. There are also suggestions of the deeply contentious and disturbing trade in human organs in China. Juxtaposed with a panoramic photograph by Jin Feng, ‘Appeals Without Words’, depicting a row of ‘petitioners’ – rural villagers bringing petitions about corruption and land seizures to the attention of provincial officials – the two works represent some of the problems endemic to a nation undergoing seismic systemic change. The petitioners in this staged photograph are painted gold because they will wait so long to be heard that they may as well be statues, and their petitions are blank sheets of paper because no-one will ever listen to their pleas for justice. The corruption of venal local officialdom is legendary, and was ever thus. “The mountains are high and the Emperor is far away,” in the words of the ancient proverb. Jin Feng powerfully draws our attention to the disparities of power and wealth in China, where mega-rich ‘red princes’ race their Maseratis and Porsches in Beijing and Shanghai whilst migrant workers sleep in makeshift tent homes beneath the freeways they are constructing. Similarly, Jin Shi’s ‘Mini-Home’, seen recently at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in the 18th Biennale of Sydney, makes visible the unseen lives of poor urban migrants, living in the cracks of the cities – alleyways, demolition zones, underneath bridges and beside freeways. The artist represents the contrast between the poverty of their reality and their aspirations by miniaturising the chaotic and cluttered temporary dwelling and all the random objects it contains. These lives are literally ‘made small’ by the inequalities of wealth and power that have emerged following the demise of the ‘iron rice bowl’ system.

Perhaps the strongest evocation of the prevalence of anxiety and the sense of an inexorably building social pressure is seen in Zhou Xiahu’s ‘Even in Fear’, a weather balloon which noisily inflates to (almost) bursting point, its rubbery skin stretched thinner and thinner, pressing against the ceiling of the gallery, and then deflates again, becoming a wrinkly empty bag. The process is endlessly repeated. The artist has said it is about “the human desire for expansion” and it certainly made me feel anxious as I stood well back and pondered the pressures experienced at every level of society – schoolchildren fearing the awful consequences of failing the ‘gaokao’ or matriculation exams; anxieties about food safety and pollution; the drive to acquire the trappings of wealth and material possessions; the anxieties over China’s position in the world; worries over who will care for the old in a generation of single children resulting from the one child policy. The artist has made a clever choice which represents cultural and personal anxiety, at the same time manipulating the personal space and the emotional responses of the viewer.

Zhou Xiaohu, Even in Fear, 2008, weather balloon and motor, size variable, image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery.

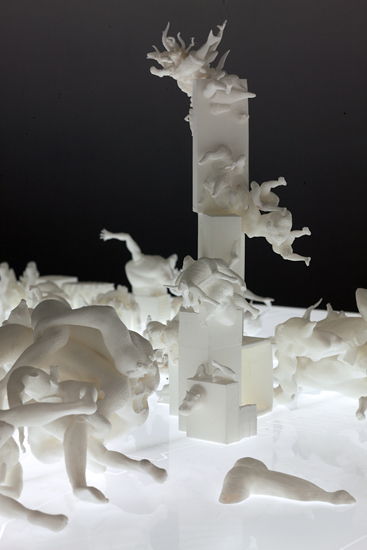

A number of works relate to the new city-scapes which have transformed Chinese geography. Zhou Jie’s ‘CBD 2010’ is a porcelain Beijing on a field of rice, deceptively visually appealing in its use of glazed white surfaces. The buildings, however, including the notorious CCTV tower usually referred to as ‘the pair of pants’ (and a few more obscene nicknames) are crawling with worm and fungus-like extrusions, covering every surface with their tentacles. For the artist they represent the metastasizing properties of urban development, which she sees as a cancerous growth, violating nature. The irony of placing them on a field of that most Chinese of substances – literally a ‘bed of rice’ – reveals the tension between tradition, history, food production and relentless modernisation. What happens, she asks, when the farms and villages are empty, and everyone has gone to a far-away factory town to work on an assembly-line making electronics? Cheng Dapeng’s ‘Wonderful City’ is a vast field of Hieronymous Bosch-like mutated creatures engaged in a disturbing variety of carnal couplings. In a milky resinous material produced by the magic of the 3D printer they perch atop city buildings like Godzilla. Reminiscent of Wu Junyong’s paper cuts and digital animations, they exude a grotesque sexual energy. Like Wu’s work they derive from a deep anxiety on the part of the artist about the soulless, money-driven, dog-eat-dog reality of the new cities of China. “Here be monsters” indeed.

Cheng Dapeng, ‘Wonderful City’ (detail) 3D prints, lightbox, 960 x 200 x 80 cm, image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery.

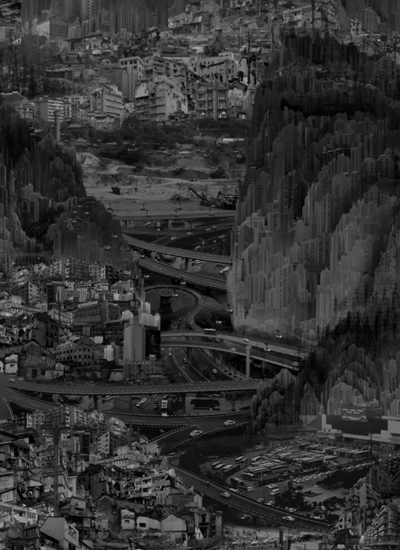

The highlight of the series of works reflecting on urbanisation is Yang Yongliang’s ‘Infinite Landscape’, a digital animation based on his knowledge of traditional ‘Shanshui’ paintings of mountains and rivers. At first glance it seems a quiet and tranquil traditional landscape until you realise it is in constant motion. The mountains are in fact towering piles of skyscrapers and the image is criss-crossed by freeways bearing cars and trucks. The arms of construction cranes reach upwards and a dirigible crosses the sky slowly before silently exploding, leaving no trace behind. The artist has said he feels “despair and sadness” at what is being lost in the relentless modernisation of his home city of Shanghai.

Yang Yongliang, Infinite Landscape, 2011, digital Blu-Ray video, 7min 30sec (frame detail) image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery.

Another highlight is Zong Ning’s series of black and white photographic works – documentations of performances with painted backdrops – in which the artist himself becomes the hybrid creatures of folk tales. In ‘Slum’ he is the spotted frog crawling out of a well, reaching desperately for the round patch of sky crossed by a bomber plane trailing smoke. In ‘Jie’ he becomes a horse/giraffe-like creature wearing boxing gloves, and in ‘Insane Desire’ he is a small greedy black figure with long outstretched arms reaching to grab an enormous breast which spurts milk into his mouth. These images are strange and menacing, reminiscent of Jean Cocteau or the surrealist cinema of Bunuel. There is a predilection for surrealism in much Chinese art – perhaps because a rich awareness of the absurdity of life and politics is so pervasive. Zong is a student of Daoist and Buddhist philosophy and hopes to point out in his defiantly low-fi and handmade works that spiritual values “are worth much more than sports cars or apartments”.

Zong Ning, Slum, 2008, inkjet print on Hahnemühle paper, 80 x 60 cm, image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery.

The enormous photographs of Miao Xiaochun reveal another element of urban Chinese life. In ‘Await’, from his ‘New Urban Reality’ series, he presents a 3-metre long panorama of people waiting for a bus in Beijing, rugged up against the cold in front of the garishly lit glass box of a store selling the consumerist dreams of Sony Ericsson and Motorola. A giant advertisement for the latest mobile phone – sleek, metallic and dangerous – hovers over their heads, an object of desire just out of reach. The longer I look at this the more intrigued I become. I want to know their stories – the unfashionably dressed migrant workers, the young girls in their padded overcoats, the man in the beanie stepping dangerously into the road. Every passenger carries shopping bags. No-one makes eye contact with anyone else. Every one of them will have a similar cell phone in their pocket. Miao reflects on the way we connect, or fail to connect, with other human beings in the 21st century.

Miao Xiaochun, Await, 2006, transparency on light box, 136 x 323 x 8 cm (detail) image courtesy the artist and White Rabbit Gallery.

Finally, Wang Guofeng’s ‘Ideality 1 – 10’ depicts the ‘Ten Grand Buildings’ constructed in just ten months in Beijing to mark the tenth anniversary of the 1949 Communist Revolution. These monuments to a socialist utopia were constructed at the time of Mao’s ‘Great Leap Forward’, now estimated to have caused the deaths of up to 40 million people in the resulting famine. Their imposing grandeur and overblown scale render the individual human being miniature and insignificant. Shot at very high resolution, with people and cars edited out and the tiny, lonely figure of the artist dressed in a Mao suit inserted into each picture (although, it must be said, I failed to find him in at least one of them, despite spending quite a while on this ‘Where’s Wally’ activity) the photographs are a cautionary tale about the unchecked power of state ideology at the expense of humanity. Now these socialist edifices seem like relics of the lost city of Atlantis, or the head of Ozymandias buried in the sand.

As you exit the gallery into the streets of Chippendale you are left pondering the many permutations of the ‘smashed palaces’ – of Imperial China in the construction of the socialist state, of the edifices of communism and the collective in the construction of a new ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’, and, of course, there are the possibilities of ‘smash’ as a noun. The collision between the individual and the state or between Chinese tradition and modernisation are just two of a number of possible interpretations. It’s a fascinating glimpse of China right now, and a curatorial conceit which is provocative and intelligent without subsuming the individual qualities of the works themselves.

‘Smash Palace’ opened on Friday 1 March and the exhibition will continue until White Rabbit closes in August for the installation of a new exhibition of works from the collection.