Guest blogger Ken Leslie gets to grips with Michael Zavros’s latest exhibition where the artist appropriates the appropriator…

Walking into The Prince by Michael Zavros at the Rockhampton Art Gallery, the first question that springs to mind is ‘Who is this Prince?’. Pretty quickly, that question fades away when you come across the astounding technical quality of the paintings and drawings. But in the back of your mind, the question of the Prince’s identity lingers on.

It’s very hard to escape the beauty of the artworks in this exhibition. Zavros has the ability to make paint and charcoal do things they really shouldn’t be able to do. You’d be forgiven for mistaking quite a lot of the pieces for photographs. They have the depth and atmosphere usually only reserved for classic photography techniques. But this is really only half of the story of what makes them beautiful images. The composition of the artworks is their key. Some of the images show wide open spaces, some of them seem uncomfortably close, but each of them is composed and cropped in a way that serves to expose the beauty of its subject.

Michael Zavros, Prince/Zavros 9, 2012.

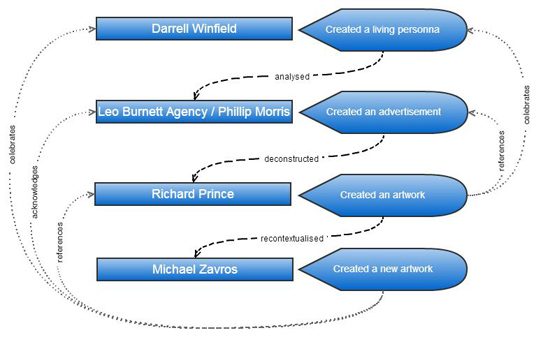

Zavros readily admits being lured in by the wonder of an attractive image, part of the reason he chose to ‘reauthor’ the enduring images of cowboys from the Marlboro cigarette advertisements, and rephotographed by American artist Richard Prince from the 1970s to the 90s.[1] These images have had quite a life. In the 1960s, Darrell Winfield was a gritty rancher who was photographed by the Leo Burnett Agency for Phillip Morris (the manufacturer of Marlboro cigarettes) to help make Marlboros seem more manly.[2] Prince, while working for publishing giant Time-Life, rephotographed the advertisements, giving an artistic reframing to the pages he referred to as ‘authorless’.[3] Enter Zavros, who has now painstakingly reproduced the same images as finely crafted paintings and charcoal drawings.

The term often bandied about with both Zavros and Prince is appropriation, which means using other people’s images in your own artwork making little changes. And although this term works really well for Prince’s rephotographs, it doesn’t quite cut the mustard for what Zavros does. Even though his works essentially look the same as the cropped, Prince images, they feel warmer now; they don’t have the cold, mercenary feel of a photo of a photo. He uses ‘the awe of a handmade object’[4] to inject the image with new cultural currency that disappeared over time with the fading of cigarette advertising from popular culture and the knowledge that rephotography is no longer a cutting edge concept. He re-energises images which are not forgotten, but are no longer blockbusters. Zavros has plucked these beautifully composed images from their twilight, and given them a new, more potent existence.

So, the Prince is Richard Prince, right? I don’t think so. It feels like a far too obvious red herring from an Agatha Christie novel. The non-cowboy images that make up the rest of the show may enlighten us a little more.

Three other sets of paintings occupy the space, a set of three nostalgic screen dumps; a series of tiny, tightly cropped images of menswear; and three opulent interiors featuring game hunting trophies. Individually, the paintings may be taken as flippant exercises in technique, but they really shouldn’t be thought of in that way. Together with the Richard Prince reworkings, the exhibition acts as a form of portraiture, building up an impression of this elusive Prince.

Michael Zavros, Prince/Zavros 10, 2012.

The advertising images of men’s suits and finery, the Suit Suite, control the viewer physically in the room. It’s made up of a large series of quite small images obviously taken from catalogues. The attention to detail in the production of the paintings draws you in, making you move very close to their surface, but the arrangement and expanse of the installation forces you to take a step backwards just to see them all together. It’s a very gentle physical manipulation of the viewer, but one that must be obeyed.

The Prince puts himself in some powerful company. Apart from the abundance of tough cowboys in the rugged outdoors and the male models clad in crisp suits, we’re also greeted by three of the coolest stars ever seen on a television screen; John Travolta, Madonna, and Betty White. You may think that this is a weird cluster of celebrities (the absence of a decent collective noun has been noted…), but each holds a particular power over us. John Travolta combing his hair has the presence of a young man who doesn’t think he’s awesome, he knows it. He’s cooler than you. Accept it. Madonna (in her prime) makes everything sexy. She’s strong and independent and untamed. She’s the wild girlfriend you never had. And Betty White is just like your mum, only way, way funnier. They all make us feel a little inferior, but in a way that we just accept and maybe even enjoy. But the paintings aren’t regular portraits, they’re presented through the visual filter that makes them accessible to us regular folk; the television screen.

Michael Zavros paints and draws things he likes.[5] The images he creates are like hunting trophies, ideas and thoughts he’s had the urge to capture and conquer, much like the luxurious interiors he’s rendered. These works are the most like a self-portrait in the show. They show a clean, orchestrated scene with polished timber floors, beautiful artwork, and the remains of a rare creature destroyed and turned into a fancy knick-knack. They show an obsession with collection and care of objects with undeniable beauty. They show understated strength and confidence.

Leaving the exhibition, you’re left with quite a clear image of the Prince. Whether that’s a portrait of Zavros himself, or an invented persona is unclear. The ambiguous Prince is strong, in charge, controlling, precise, analytical, and nostalgic, but without being overbearing, pompous, or in your face. The Prince has a definite royal air about him, head held high.

[1] Zavros, M. Interviewed by: Leslie, K. (15 February 2013).

[2] Lichty, R. (c.1977) Darrell Winfield, Marlboro Man. [PDF]. Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, UCSF, fhq51b00. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fhq51b00/pdf, [online] [Accessed: 16 February 2013].

[3] Prince, R. (1992) Interview by Larry Clark. In: Prince, R. and Kawachi, T. eds. (1999) 4X4. New York: Powerhouse Books, p.94.

[4] Zavros, M. Op Cit.

[5] Ibid.

Ken Leslie is an artist and primary school teacher living in Rockhampton, Australia with his beautiful wife and his two amazing children. He’s a keen believer that the arts are an essential part of life, and that looking at and talking about art will not only make you a smarter person, but also a better person.

He is yet to be proven wrong about this. His blog is Why Am I looking At This?