Luise Guest on the life and work of Lin Yan and the dimensional bridge between philosophies and aesthetics…

Lin Yan with her work Sky 2 at White Rabbit Gallery, image courtesy White Rabbit Collection, photograph: David Roche

Three cities, three histories, and three artistic languages co-exist in the work of Chinese artist Lin Yan, who was raised in Beijing and studied in Paris before moving to the USA, where she now lives and works in New York.

Lin was born in 1961 to a family with a distinguished artistic lineage —both her parents and two grandparents were famous artists. Like other intellectuals, writers, artists and teachers, they suffered through the changing political winds of twentieth century China. Lin studied at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts, entering in 1980, only two years after it had re-opened at the end of the Cultural Revolution. After graduation, she followed in the footsteps of her mother and grandfather, studying in Paris before moving to the United States in 1986. Today, she works in her Long Island City studio, travelling back and forth between New York and Beijing several times each year.

Best known for working with paper, Lin Yan bridges the divide between two and three dimensions (she calls it working in ‘two and a half dimensions’), and between Chinese and Western philosophies and aesthetics. She blurs boundaries, embraces paradox, and juxtaposes past and present. I wanted to learn more about her journey from one culture and visual language to another, and to discover how her beautiful, fragile works encompass past and present. While the artist was in Sydney to install her work at the White Rabbit Gallery we spoke about her early life in Beijing, and how she thinks about her practice: what follows is an abridged and edited account of a much longer conversation.

Luise Guest: I’d like to ask about your early life, growing up in a family of artists in Beijing. Your parents were modernist artists and influential teachers; I know that your mother, a printmaker who had also studied in Paris, at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux Arts, was Xu Bing’s teacher, for example, and your father, Lin Gang, had studied in the Soviet Union. Your grandfather, Pang Xunqin, was a very famous modernist artist. How do you think these early experiences influenced you? And what are some of your most vivid memories of your early childhood growing up in this artistic milieu?

Lin Yan: I saw my parents doing paintings a lot when I was young, but not my grandfather, because he was accused of being a Rightist in 1957 before I was born. [Mao’s Anti-Rightist campaigns began in 1957: more than half a million intellectuals, students, artists and ‘dissidents’ were persecuted. Many were executed, imprisoned or sent to labour camps. Lin Yan’s grandfather was made to clean toilets and forbidden to make art, blacklisted for more than twenty years.] Actually, I didn’t really meet him until I was ten or eleven years old. Of course, I had met him when I was a baby, but I couldn’t remember that, I just saw the pictures. My earliest memory of him is from the time during the Cultural Revolution when my parents had been sent to a labour camp along with all the other professors from the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and I was staying behind in Beijing, living with neighbours. On my way home from school one day I saw an old man with white hair standing in front of the gate … he was staring at me. I asked if he was looking for someone, or if he wanted to come into the yard, and he said, ‘Are you Pang Tao’s daughter? I am your grandfather.’

Lin Yan, Sky 2, 2016, paper and ink, 330 x 1600 x 520 cm, image courtesy White Rabbit Collection, photograph: David Roche

Pang Xunqin took Lin Yan to eat lunch in the only restaurant in the neighbourhood – she remembers that she ate Peking Duck, a very great treat at that time. ‘He didn’t eat himself, he just watched me eat. The whole experience was so lovely, so nice, and that was the first time that I really understood what a gentle man could be.’

Her parents were permitted to return home in the late 1970s, reinstated to their teaching positions when the art academy re-opened. At that point her mother, Pang Tao, could visit Pang Xinqun once more, and she began to take Lin Yan to see her grandfather every weekend. As she grew older, they would talk about art; Pang taught her about colour theory, and showed her how to use line more expressively. As a young man, he had co-founded the Storm Society in Shanghai, an avant-garde group with a radical manifesto; in contrast to the academic traditions in which her parents had been schooled he believed in spontaneity of line and form, and encouraged her to experiment.

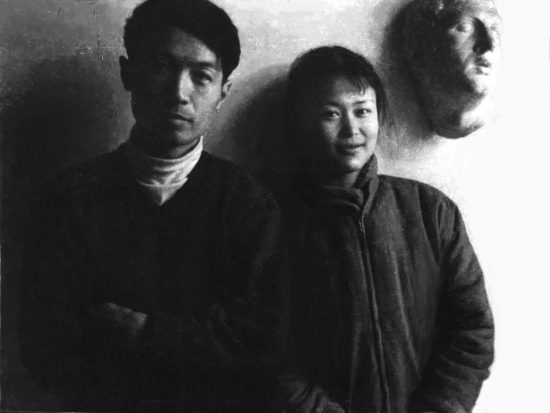

Lin Yan’s parents, Lin Gang and Pang Tao, in 1958, image courtesy the artist

LG: You had this incredible advantage in being taught by someone who had honed his skills in Paris in the early years of the 20th century — your grandfather was such an important Modernist artist.

LY: Yes. And my parents, of course, were realist academic artists –– they knew how to observe objects and paint them realistically –– but my grandfather was a modern artist and open to all kinds of styles. So, in my early years of learning art I always wanted to try different ways, which maybe made me different from other art students in those days. But my father influenced me a lot too –– his work is really powerful. He told me, ‘When you do your work, if you have one sentence to say, you just say that one sentence and you don’t need to say more. If you are moved by something and you do a painting, it will move the viewers. If you are not moved by something and it isn’t meaningful for you, then your work will never convince others’ … I always try to remember that and stay true to myself. Looking back, I am grateful that I tried to make my work as powerful as his, but that I can start from a tender point. I can use softness to express power and force.’

LG: You entered the Central Academy of Fine Arts when it had only recently re-opened after the Cultural Revolution. Can you tell us what it was like to be an art student in Beijing in the early 1980s? What was the atmosphere in the art academy?

LY: Yes, at that time the first group of students to enter after the Cultural Revolution was only two years ahead of me. I entered the CAFA oil painting department in 1980 and graduated in 1984. That was such an interesting time. Everybody was so excited, the students and the professors. There were only eight students in each class, so the whole school was really small and we all knew each other –– through our whole lives we have followed each other’s career paths … Students were so curious to learn, they were thirsty to learn. Even though we didn’t have classes in the afternoon, we stayed in the classrooms…we painted during the day and read books at night.

Lin Yan as a student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, 1982, image courtesy the artist

Chinese artists in the mid-1980s were just starting to be allowed access to western books and ideas. Some have likened that time to a window slowly opening, as China began to engage with the outside world after the death of Mao Zedong. Leaving Beijing at the end of 1984, Lin Yan missed the excitement of the avant-garde ’85 New Wave movement that swept across China. Instead, she discovered Modernism at its source.

LG: And then you went to Paris! Arriving in Paris in 1985, coming from a Beijing that was so different to the huge global city that it is today, must have been a profound culture shock. What were your most vivid impressions – and how important was Paris to you in changing your direction as an artist?

LY: I was 22 or 23, so that was a great adventure. It was really exciting to be away from home. I noticed that I didn’t need to compare myself with other students because their work was so different. So that was the moment when I started a conversation with myself that continues, about who I am and what path I should follow. I grew up a lot, yes. And it was also the first time that I saw the museums. In Beijing, I studied oil painting for four years and I only saw paintings in books. To see them close up, to see their texture — that was so rewarding… In the Pompidou, I saw all the abstract art and American art and Pop art, so different from the traditional surroundings and architecture in Paris, and I thought, ‘Where did all this come from?’ I wanted to see the whole thing, from traditional to contemporary art, to understand where modern art and contemporary art came from. I wanted to go to New York to see! As soon as I got to the United States I immediately felt that there was such an open field in front of me and I could literally do anything I wanted to do in my artwork.

Lin Yan’s early years in the United States, where she established herself in New York after completing her MFA at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania (a college she had chosen by examining a small map, under the erroneous impression that it was close to the galleries and museums of Manhattan) reinforced her sense that the creative possibilities of materials were unlimited. She was interested in Minimalism, and came to especially love the black sculptures of Louise Nevelson, two influences that would come to inflect her own mature work.

LG: Today, as you move between Beijing and New York – where is your heart?

LY: The subject of my work, if there is a subject, is all related to China, and to Beijing, and to the issues that bother me, or things I feel disturbed by. The first trip back to Beijing after I left was eight or nine years later in 1994. I had planned to stay in China for three months but I was so shocked by what had happened to Beijing that I couldn’t help doing artwork to express my feelings. So I extended my stay to six months and I had a show there. I finished three major works in my parents’ house. That was the turning point for me, from my coloured period to a totally black period. I didn’t plan to do that, I just wanted to express what I felt about the traditional Beijing hutongs, the old architecture having been demolished so violently, so brutally… I know it’s part of development but I just couldn’t accept it. The second big punch like that was in 2013 when the air pollution was so severe and I just couldn’t’ stand it, and I felt once again that I had to do something to express myself. We have a right to breathe. We have a right to complain, to urge the government to change it, to do whatever they can to make it better. I just couldn’t keep silent.

Lin Yan, Inhale, 2014, ink, plastic bag, light and Xuan paper installation, 765x508x190cm, image courtesy the artist, photo: Jiaxi Yang

Lin began to use Chinese paper to cast fragments of old Beijing architecture — roof tiles, bricks and eaves — in works that hovered between painting and sculpture; the embossed details of traditional Chinese buildings are like bleached bones, the fossilised remnants of a disappearing way of life. This paper – appearing fragile yet surprisingly strong — suited her interest in Buddhist philosophies of non-attachment and the binaries and paradoxes that recur in her works. She began to make ambitious, immersive installations that echo her love for architecture and express her sorrow at what has happened to her city.

Lin Yan pleats, drapes, folds, sheaves, crumples, cuts and layers soft handmade Xuan paper. Sometimes stained, even saturated, with black ink, her works remind us that ink and paper are the essential Chinese materials for both art and writing. Floating in the gallery space, suspended by fragile threads, the crumpled, twisted, grey and black forms of Sky 2 evoke brooding grey skies over polluted Chinese cities. They contrast with sheaves of pleated white paper that hang behind them, a curtain that shifts gently in every current of air, as if breathing. Overhead, the soft, hollow forms of paper stained with black ink loom like storm clouds.

In the interests of full disclosure, Luise Guest is the Director of Education and Research for the White Rabbit Collection of contemporary Chinese art. She spoke with Lin Yan in Sydney during the installation of her work in The Dark Matters at White Rabbit Gallery. ‘The Dark Matters’ continues through 30 July 2017 at White Rabbit Gallery, 30 Balfour Street Chippendale, Sydney, 2008. www.whiterabbitcollection.org