Reviewed by Luise Guest…

Jin Sha, Salute to Masters – Conversation with Piero della Francesca No 1, 2011, ink and colour pigment on silk, 33cm x 47 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist and Janet Clayton Gallery.

The ‘gong bi’ style of traditional Chinese painting was characterised by exquisite brushwork and superb draughtsmanship. Artists were skilled in rendering figures, landscapes and objects in meticulous, almost hyper-realist detail. This approach is a continuing thread in contemporary Chinese painting. When John McDonald opened the new exhibition of Chinese artists at Janet Clayton Gallery From Paper and Silk’, he made the observation that these works, contemporary though they are, can be identified with the traditions of the extraordinarily skilful imperial master painters. Even today, graduates of Chinese art colleges and training institutions, such as the elite Central Academy of Fine Arts in Bejing, have been schooled in a rigorous academic program with an emphasis on mastery which has long since vanished from western tertiary art training. Artists emerge from this arduous training with unparalleled technical skill, like that of an apprentice in a Renaissance master painter’s workshop. They also emerge with an ability to translate this knowledge into conceptually challenging practices and a drive to make art which turns a critical and highly aware eye on their own society.

This exhibition resulted from an exchange project with Beijing Art Space. The works were selected by the artist Jin Sha, whose work has been seen recently in Australia in the ‘Zhong Jian’ exhibition which he curated, shown originally at the Wollongong Regional Gallery, then touring a number of regional galleries before finishing up at the Mosman Regional Gallery last year. That exhibition introduced audiences to his practice of ‘reimagining’ iconic works from the western tradition, which turn out on closer inspection to have a sly sting in the tail, distinguishing them from the kind of appropriations we grew rather tired of in the 90s.

The exhibition may disappoint audiences expecting to see original works painted directly with ink onto silk and paper in the Chinese manner, as most of the pieces in the show are in fact digital, printed in limited editions from the artists’ original works. While the awareness of the immediacy of the artist’s hand on the surface is missing from the experience, there is still much to enjoy. In part the choice to print digital images onto silk and paper reveals the wonderfully pragmatic adaptability of Chinese artists as they weather the vicissitudes of political, social, economic and cultural change. The decision to send digital prints on the long journey from one end of the earth to the other makes sense, and the artists were at pains to point out that it gave them greater control over the colour and final appearance of the images than traditional printing processes would allow. I tend to think that if the master painters of the Ming Dynasty had been able to access high resolution colour printers they would have embraced the technology with alacrity. Jin Sha says of the two materials, paper and silk, “This exhibition is talking about paper as a connecting force between the old and the new, as well as a link between very different lives. Paper is the key to link the Chinese with the West.”

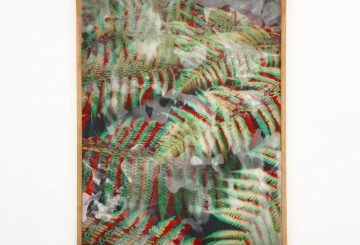

Zhu Zhengming, ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude No. 4’ 2012, Digital Print on Silk, 32 x 51 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist and Janet Clayton Gallery.

In the series of four works by Zhu Zhengming, ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’, melancholy heads drawn with a beautifully simple economy of line are anchored by the empty space surrounding them. Everything matters and is carefully considered – the space is as important as the subjects. Three of the characters wear or carry masks, while a red-haired woman appears to have snakes coiled around her neck. They glance away, refusing to meet our gaze. The works are mysterious, poetic, evoking a profound sadness.

Lu Peng, ‘Crane’, 2012, Digital Print on Paper, 51 x 45.5 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist and Janet Clayton Gallery.

In contrast Lu Peng’s works are theatrical explosions of billowing, floating fabric swirling around complex arrangements of characters engaged in mysterious rituals. The artist has said that his work is about “the fall of the human race into a trance that is the current contemporary dream”. In ‘Crane’ we see two characters tenderly holding birdcages and a third perched on the back of a crane, representing one of the immortals. An angel-like persona swoops down from on high. The space is as groundless as the gold background of a medieval altarpiece, and as fantastical. This artist’s complex and dynamic works suggest a world in flux, where normal boundaries shift and dissolve and we are all subject to the caprice of the gods.

The highlight of the exhibition, however, is a series of works by Jin Sha. His technique is flawless and his ‘Salute to Masters – Conversations’ series allows him to combine technical wizardry with wit and humour. The underlying intention is a serious one, however. In his version of Piero della Francesca’s Duke and Duchess of Urbino the two Italian aristocrats are presented as literally disembodied – empty suits of clothes against a background in which some unpleasant things appear to be happening. Volcanoes are erupting, tiny warships are visible behind the Duke, and planes are circling overhead. The world is clearly unstable. The effect of this disruption to such familiar art historical images is unsettling.

Jin Sha, Salute to Masters – Conversation with Piero della Francesca No 2, 2011, ink and colour pigment on silk, 33cm x 47 cm, image reproduced courtesy of the artist and Janet Clayton Gallery.

In the Piero della Francesca painting Duke Federico da Montefeltro is represented as the master of all he surveys, including, no doubt, his much younger bride, Battista Sforza. Here, however, he becomes just a red hat (which may as well have sat on the head of a Chinese emperor as on the Italian Duke) and a red suit perched on the window ledge, all pomp and no circumstance. Magritte’s famous pipe, floating absurdly in front of his missing face, suggests that we should question what we see and take nothing for granted; everything might be other than it appears to be. The representation of worldly secular power is punctured and revealed to be made up of nothing at all. It’s not such a stretch to think about the way that in China all conversations about power – dynastic or political – are necessarily carefully coded. Meanings are hidden and revealed quite strategically.

The Duchess of Urbino no longer inhabits her elaborate head-dress, which now becomes an ornate empty shell. One of Magritte’s apples dangles in the air in front of where her face should be, perhaps representing the temptations of worldly wealth and power. These two aristocrats, however, are now literally ‘no body’. They are invisible, hollow and absurd. Their clothing and the symbolism of the masculine pipe and the apple of temptation suggest that both man and woman have been expelled from some garden of Eden which they themselves have destroyed. The biblical text the artist has chosen to paint underneath Battista Sforza is pointed: “For men will be lovers of themselves, lovers of money, self-assuming, haughty blasphemers…..”

I asked Jin Sha why he selects such iconic images from the western art historical canon – Durer’s ringleted self-portrait in the Zhong Jian show; and in this one, Bellini’s powerful Venetian Doge, all gravitas and brocade, as well as Piero’s double portrait. He told me that he appreciates the interplay of east and west, past and present, and enjoys playing with symbolism. “In Salute to the Masters – Conversation with Piero della Francesca No.2, I’ve appropriated Magritte’s iconic image ‘This is Not a Pipe’ … referring to the temptations of man. I’ve also drawn from Biblical passages, to reinforce the imagery, the apple as a symbol for sin, for example.” He alludes to the notion of apocalypse in these works, to the destructive power of nature, and to the impact of mankind upon it, a common theme in the work of Chinese artists, which is hardly surprising when one considers the pace of Chinese modernisation and the consequent environmental damage.” In China, we have developed economically very fast, but in other ways we have lost our sense of tradition, we have lost our respect for culture and we have little power to stop this”, says the artist. “If only we could slow down”.

Perhaps the work of the seventeen artists in this exhibition represents a ‘slow art’ in opposition to the whirlwind pace of change; a way to reconcile Chinese traditions of ink painting, literati painting and ‘meticulous brush’ painting with the desire to reflect on contemporary life in all its complexity.