From Luise Guest…

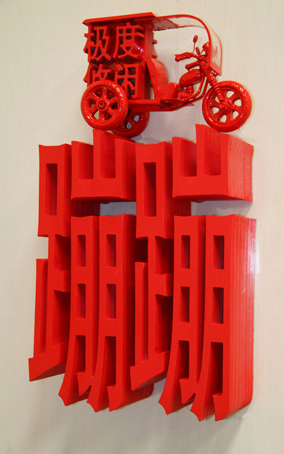

Shortly after I had returned to Sydney from my first trip to China, I saw Laurens Tan’s work ‘Babalogic II’ in an exhibition called ‘Zhongjian’. A gleaming white model of Breugel‘s ‘Tower of Babel‘ (or is it?) balances on a white three-wheeled vehicle of the kind that are seen everywhere in Chinese cities. These ‘sanlunche’ are used to carry everything imaginable from firewood to recycling, from farm produce to huge loads of industrial piping and household goods. In a rapidly modernising China they are considered unstable; an undesirable reminder of ‘old China’.

Laurens Tan, Babalogic II, Installation View. Computer-cut ABS, Light, Custom Sanlunche, Dual-Channel Projection, Variable Dimensions, image courtesy of the artist

Tan is exploring the impact of rapid globalisation and massive urbanisation on China’s language and culture through the recurring motif of these vehicles. Video screens form an integral part of the work, flashing Chinese characters onto the architecture of the tower of Babel – that reminder of the presumption of humans, punished by being rendered incapable of communicating with each other. Mesmeric images of blinking eyes create a disquieting sense of anxiety. Mandarin words echo through the gallery space, underlining the frustrations of attempting to communicate across cultures. Tan is especially interested in language systems and the complex nuances of linguistics. With this visual metaphor he communicates his own paradoxical sense of being both foreign and Chinese in China, where he has worked since 2006. The title of this curated show may be translated as ‘in the middle’ or ‘midway’ and it featured the work of Chinese artists living and working in China juxtaposed with Chinese-born artists living and working between the two countries and Australian artists whose work is informed by China in some way. Interestingly, as I discovered, Tan could fit all of these categories, or perhaps none of them. He is something of a nomad, and moves chameleon-like across boundaries of culture and language.

The artist divides his time between Beijing, Sydney and Las Vegas, where, by his own account, he is rather a success at the blackjack tables. Born in the Netherlands of Chinese parents whose families had originally migrated from Fujian Province, he grew up in Singapore and Indonesia before coming to Australia at the age of 12, thus developing a somewhat multi-layered and complex identity. His work has focused increasingly on notions of risk, chance and entertainment in the context of urban spaces. A long term interest in games of chance and risk resulted in a ten-year design research project investigating how risk plays out in urban spaces and interpersonal communications, and his doctoral dissertation ‘The Architecture of Risk’. Fusing sculpture, architecture, design, video and music engineering, Tan embodies a new spirit in art which increasingly sees old boundaries between these different modes and genres as irrelevant, and the form of an artwork as something which is superimposed upon and driven by the conceptual intentions of the artist. “Art is a vehicle for thinking”, he says, “not a by-product of a commercial drive.” He has developed a visual language of form and space which conveys challenging ideas in engaging and deceptively simple ways.

His work has been seen in Sydney this year in ‘Snake Snake Snake’, an exhibition of Asian Australian artists, and in 2011 in ‘ZhongJian’, which travelled regional galleries including Wollongong and Mosman. Past solo shows include ‘Happy Toy’ at Tally Beck Contemporary New York; ‘Chinese Toy Stories’ at Redgate Gallery/Opposite House Beijing () and ‘The Depth of Ease’ at Anniart Gallery, 798, Beijing.

Laurens Tan, Beng Beng Prototype Made in China. Fiberglass, Steel, Acrylic, Plastic, Wood, Baked Enamel, 62 x 30 x 11 cm, edition of 8, image courtesy of the artist.

Tan went to China in 2006 knowing little Chinese, an overwhelming experience which further developed the focus on language and text in his work. Since that first Australia–China Council residency at Redgate Gallery in Beijing he has used Chinese characters as an integral element in his sculpture, video and digital installations. His work is witty and playful, reflecting the sense of delight and discovery of the non-native speaker venturing forth in a new language. In his three-dimensional work the Chinese characters take on a solidity and materiality – they are sculptural structures carved in high relief that embody meaning in a literal way. Paradoxically, they also convey the ways in which meaning is elusive and ambiguous as it is so context-dependent. In his work language is at once solid and ephemeral.

We met in the café of the Art Gallery of New South Wales to talk about his practice. What follows is just part of a long conversation.

LG: Much of your work explores ideas about language and the ‘slippages’ in communication between people and between cultures. What is it that interests you about these ideas?

LT: I grew up speaking Dutch, before I spoke English. My father spoke Cantonese, not Mandarin, and I learned some Chinese characters in an Anglo-Chinese primary school in Singapore. Every other kid had some Chinese and I felt like the dunce… When I came to Australia I was 12 and there was a pronounced sense of being an outsider, being foreign. It created in me something like an inferiority complex. It made me carry some kind of issue with me, all the way down the track. Even though you outgrow it or intellectualise it, and the culture itself maybe outgrows it, the remnants of how you felt are always hard to get rid of. When I went to China I thought, “Phew, finally I’m not a foreigner anymore!” even though I can’t speak fluent Mandarin. I had tried to learn Mandarin before I went to Beijing in 2006 but it was a little bit half hearted…

LG: What happened when you went to China?

LT: There were three or four key exhibitions for me in Beijing. The curator, Wu Hung from Chicago curated an exhibition with big names such as Shen Shaomin, Miao Xiaochung, Qiu Zhijie… there were 12 Chinese artists – I don’t know how I got in there! I was the only non-national. ‘Babalogic’ was actually commissioned by PKM Gallery, a Korean-owned Gallery in Caochangdi. I was very privileged and honoured that what I was talking about actually seemed to have some currency in China. That show was called ‘2D/3D: Negotiating Visual Language’. The next thing that happened was a show at Iberia Center. That was probably in the top three of the non-profit run spaces along with Today Art Museum and the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art. I was again chosen for that show along with all Chinese artists, and then the third exhibition was a collaboration with Dong Bing Feng and Karen Smith in a thing called ‘Fat Art’. The three curators came to my studio and said, “What have you got?” so they must have heard something about what I was doing.

LG: Did your interest in language systems and in a specifically Chinese identity predate your visit to China?

LT: Before I graduated my major was in ceramics, and painting – actually painting was a minor – but after I graduated, in fact in my final year, I closed the book on oriental ceramics to see if there was something innate about form, balance, symmetry…something that I could read as being innate. I had no other connection with my past. The same with my painting – I was using a calligraphy brush and looking at Chinese painting. When I transitioned from clay to sculpture and steel I was using three-wheeled carriage structures. I’ve only just realised that I had been looking at this before, the stability of the 3-wheeled structure. Now I can see there is a connection with that first series I made in China, which can be translated as ‘The Ultimate Relaxation’ or ‘The Depth of Ease’. [The exhibition of this first series of works was shown in Beijing. The catalogue essay interpreted the works as Tan’s response to the plight of Chinese cities – an “inevitable erosion of cultural identity” (Felicia Florine Campbell). All the diverse three-wheeled vehicles on Beijing’s streets were his first source of inspiration, as they reflected the fragility of a unique utilitarian urban culture.]

Laurens Tan Dan Sheng (Birth) 2009 (Depth of Ease series, Version 1). Fibreglass, Steel, SanLunChe Parts, Baked Enamel, 109 x 135 x 274 cm, image courtesy of the artist.

LG: So that series of works really first developed when you saw these typical 3-wheeled vehicles in the streets of Beijing?

LT: Yes. I had applied for a second residency, I had group shows and teaching lined up. I wanted to do the same thing again in another residency a year later. I think the exhibition of that work was in May 2007 – my first solo exhibition in 798 [‘798’ is an art district in Beijing]. That exhibition ‘The Depth of Ease’ was very well received in the Chinese media which was in a way a bit of a trap because I was then expected to repeat myself. It was the first series I made since leaving Australia – in a way I am trying to decipher how I think, how I work, shaking the tree to see what falls out. I always tend to work in series to help me see the limits of an idea.

LG: Was there a big break between the work you were making here in Australia and in China?

LT: Kind of yes and no. The language and the urban sites (in Beijing) unravelled everything. In retrospect there is a link, I can see the connection now, looking back. I wasn’t actually trying to emphasise the next stage. But obviously the same concerns resurfaced.

LG: Where did your ongoing fascination with games and chance come from originally?

LT: I had an exhibition called ‘Games And Voices’ in about 1990 at Macquarie Galleries before I had ever set foot in Vegas. It was a language about basically how to skin the other guy! (laughs)

LG: Is a work like Babalogic the culmination of that series of works that you developed in the residency?

LT: In a way yes, but I can only see that in retrospect.

LG: Your work has been described as blurring the boundaries between sculpture, product design, music, architecture and graphics – is that how you see it?

LT: Probably, yes. I moved from drawing and charcoal – tactile, analogue work – to design and digital work in the early 90s, actually when the first Apple computers came out. Remember the floppy discs? They didn’t have 3D then. You could get something called MacDraw, a precursor to Illustrator, so I designed my first piece on that. And video came about the same time. I went to Paris for a residency in about 1990 and bought a video camera. My first video project was based on documenting the different Statues of Liberty by Bartholdi for a show at the embassy there. While I was working with video I discovered effects and it was a whole new thing. In the first half of the 90s that’s basically what I was doing, installations with video. Animation didn’t come till a bit later, until I mastered Strata Studio Pro which now is a bit of an antiquated thing. But I was getting so fast at it that if I needed to do anything more accurate or use other software I could get assistants… the ideas came so quickly and you could invent so many things including product and industrial design. This ability to invent in space is as good a way to narrate as anything, about culture or whatever…

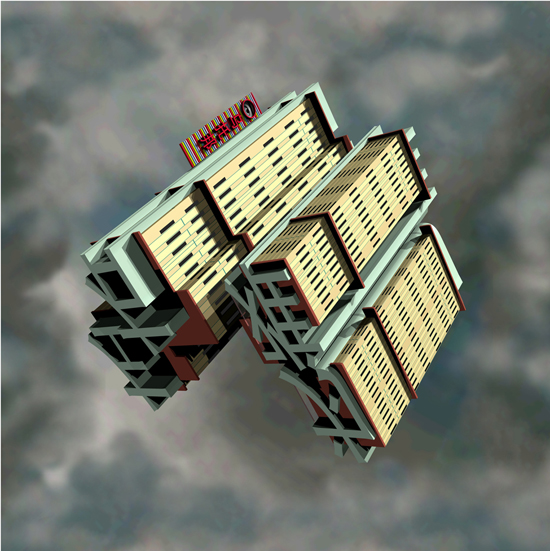

[Tan has previously said that he became interested in working in architectural space from that point onwards, as well as in CGI special effects. Since 1994, 3D modelling and drawing with geometry have been significant elements of his practice, linking animation, photomedia, and industrial design to architectural prototyping and sculpture.]

Laurens Tan, Happy Toy 2011. Still from 3D Modelled Animation, Infinite Loop. Soundtrack: Laurens Tan, Daniel Ferrera, image courtesy of the artist.

LG: Do you think that in China the traditional boundaries between art and design are more blurred? Is there a greater freedom and fluidity to experiment, and more overlapping of disciplines?

LT: I think there is everywhere – if you look at movies they depend on special effects and 3D now – you create a fantasy in the computer. If you want an elephant to walk on your back, you don’t need an elephant anymore! I think it’s part of contemporary culture. Fantasy is much more easily created and it’s much more believable now. Occasionally I still have an urge to do something in the analogue world, like drawing. It’s a part of my practice that I would like to have come back. Actually what is happening (in my work) is music. Years ago, I did the theory and arrangement course for a year, and that has stuck. In Las Vegas I collect Fender guitars and amplifiers – it’s actually quite a cheap place to buy houses, cars and guitars. I couldn’t possibly have this idea of a collection in Beijing, or in Sydney. The music has something like an analogue sense, how you strike the strings has consequences. It’s like a paintbrush.

LG: How do you envisage using that in your practice?

LT: I have actually used it as a soundtrack. In the past I might have borrowed a piece and would have to select from what I hear and what I find, but now the difference is that I can create. It will take a while before what I create can surpass what I can find, but the difference is that it’s custom made. Working with computers – as a world it’s limitless, which is great. But music gives you that sense of performing. The risk of failure is always there. If you get it right, and you improvise, and it works, then suddenly there’s another future of possibilities.

LG: Why the move to Las Vegas?

LT: After 6 years in Beijing I needed a new or an additional stimulus. I went to the US 4 times in the space of 18 months. I had thought of buying a house in Vegas twice before. I didn’t go there because of art! Vegas is calming, like a hide-out. I’m in solitude there. In Beijing you’re in the traffic, which facilitates ideas and projects, but Vegas is more like a void. It’s like the opposite of Beijing. Beijing – it’s a love/hate thing. In Beijing it’s quite clear, I get quite frustrated with the non-logical manner of how things work or don’t work and the chaos. The love part is also quite clear – the Chinese language has such depth, and I don’t think I could ever find that anywhere else. I’ve got a bit of a handle on that now, extracting possibilities.

LG: Back in 2010 you told a journalist that you chose Beijing because you wanted to go somewhere “open-ended and open-minded”; somewhere that was a “cultural crucible”. Is Beijing still that place?

LT: I can answer that in a different way. I went to Istanbul last year. Istanbul had a similar effect on me to Beijing when I first went there – I couldn’t understand the language, it has a very strong feeling about contemporary art in the best sense of the word – contemporary art operating as a vehicle for thinking, not manufactured or synthetic, actually a direct hit, a commentary on what is happening. I thought Istanbul was very similar to how Beijing was when I first came. It’s like 80s music which at the time was so experimental and exiting and now it’s lovely to hear it but it just doesn’t have the same punch. I go back to this love hate thing… you can’t keep travelling around the globe looking for a thrill!

LG: So you’re not about to move to Istanbul?

LT: (laughs) I wouldn’t knock it totally out of contention.

LG: Will the use of text and Chinese characters continue to be a central element in your practice?

LT: The other language that intrigues me is actually Ottoman script.

LG: Is there pressure on you though to make work that looks Chinese?

LT: Well in fact the reason I don’t feel that pressure is because even though I don’t speak the language fluently, people – not just artists but just generally ordinary people in the street – can read my work in a Chinese way. The humour or the little puzzle, the idea being hidden in a puzzle, they get it. Relationships between people or values – it seems to all be easily understood or legible. I didn’t have to make any changes. The way I was interpreting Chinese heritage, culture and attitudes, automatically was understood. Because of the difficulties I had with the Mandarin it gave me an opportunity to look at these instances in a way that someone who was fluent in Mandarin would not do.

LG: Does this mean that Chinese audiences see your work very differently to western audiences?

LT: Yes I think you’re right. Yes because I actually use Chinese characters as a prompter or a clue. [He shows me a series of works based on the ChengYu, a 4-character idiom which is a significant traditional conventional form reflecting Chinese philosophy and morality] For example this is a series of buildings which reference Beijing….so it’s a commentary on the changing city, on urban planning. So each building was built around a character. Can you read that? [LG: ‘Sorry, no, I can’t’] It says “I can’t tell my left from my right”. So the characters themselves get through to a Chinese audience in a particular way. An English speaker would get something different out of this than a Chinese audience.

Laurens Tan, Hotel Utopia at Dusk 2009. (‘zuoyouweinan’ – I don’t know my left from my right). 3D modelled photomedia editioned inkjet print. Framed Archival Hahnemuhle Fine Art Pearl 285 gsm paper edition of 8, image courtesy of the artist.

LG: In your work teaching at the Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts what do you notice about the young generation of Chinese artists and film-makers?

LT: They are in a way drifting away from tradition but [in the research projects they undertook with Tan] they were actually quite keen to do an about face, to talk with their grandparents and find out about their own history. They are driven by the technical and the technological. The first thing I did was looking at civic space – who decides what public art goes somewhere and what the people or residents think about it. They had never even thought of that. Also they had never done any sculpture or public art. Having to interview people and extract an opinion meant they had to learn about design and methodology which was all new to them. For each project we had to come up with a seamless video documenting 17 different projects which were not cacophonous, so there was a lot of technical stuff which was what they had come to learn. But this was meaningless without the context.

Laurens Tan Code (2009), Animation Infinite Loop, 2009. ANZ Australian Film Festival, Sanlitun Village, Beijing December 2009, image courtesy of the artist.

LG: You have told me about playing blackjack, and your doctoral dissertation focused on ideas about risk. Is the artist inevitably a gambler?

LT: The simple answer must be yes. I mean there are different ways of operating as an artist but essentially I think art is always about embracing risk and letting go. And that’s the hardest part.