Luise Guest visits the Gallery of Modern Art for Falling Back to Earth where beyond the spectacle lies meaning, wit and subtlety…

As I stood on the down escalator in Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art two teenage girls wearing cardboard wolf masks slid silently past me, going up. The surreal nature of this encounter encapsulated my experience of Cai Guo-Qiang’s ambitious project for GOMA, Falling Back to Earth.

Cai Guo-Qiang, Heritage, 2013. 99 life-sized replicas of animals, water, sand, drip mechanism; installed dimensions variable

commissioned for the exhibition ‘Falling Back to Earth’, 2013; proposed for the Queensland Art Gallery collection with funds from the Josephine Ulrick and Win Schubert Diversity Foundation through and with the assistance of the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation.

“And what is it about Chinese artists and taxidermy?” I wondered, as I stood with a crowd of Queensland families (the exhibition has been enormously popular, attracting an average of 1150 visitors each day) around the waterhole that forms the central element of his enormous installation, ‘Heritage’. From Huang Yong Ping’s bats, wolves and taxidermied animal heads to Cai’s earlier celebrated installation ‘Head On’, seen once again in Brisbane, the common factors apart from the use of real or replica animals are the scale of their allegorical ambition, and of course the literal physical scale of the works themselves. In ‘Heritage’, 99 animals, predators and prey alike, stand with bent heads in a peaceful coexistence, an allegory of utopian harmony. Sculpture as spectacle.

Cai’s works are never mere spectacle, however, despite his controversial fireworks for the Beijing Olympics opening ceremony. His work is based on investigations of philosophy, history, and Chinese tradition. These layered and complex meanings, as well as his wit, are revealed in the work he created for the 1995 Venice Biennale, ‘Bringing to Venice What Marco Polo Forgot’. In a wry reference to the theory that Marco Polo never in fact reached China (he failed to mention tea in his account of his travels) and a reflection on the different histories and cultures of east and west, a Chinese junk moored at the historic Palazzo Giustinian-Lolin contained a vending machine dispensing Chinese medicinal tonics to visitors. Sydney audiences would be familiar with Cai’s exploding cars, in ‘Inopportune: Stage One’ in its Cockatoo Island version at the 2010 Biennale of Sydney.

Born in Fujian Province in 1957, Cai is best known for his use of gunpowder as art medium. Gunpowder, ink and paper – those significant Chinese inventions – all come into play in his practice. His first fire works date back to 1984, when he began exploding gunpowder onto canvas and paper as a way of ‘drawing’ which owes something to the calligraphic mark of the ink painter in Chinese tradition, and something to the ‘Laws of Chance’ of Dada. They also reference his childhood memories of witnessing skirmishes along the ‘Fujian Front’ between China and Taiwan. The artist describes his work as “like making medicine — a little of this, a little of that, watch it and taste it a little and see how it is working.” There is something of the alchemist in his ephemeral site-specific installations. The first open air pyrotechnic project took place on the River Tama, near Tokyo, in 1989. Cai loves the binary notions of destruction and rebirth, and connections with Taoist philosophies. Critic Fabio Cavalucci describes Cai as “working on the thin line that separates the possible from the impossible” and, indeed, his two previous works for Brisbane have shown all too clearly the precarious and unpredictable nature of his chosen medium.

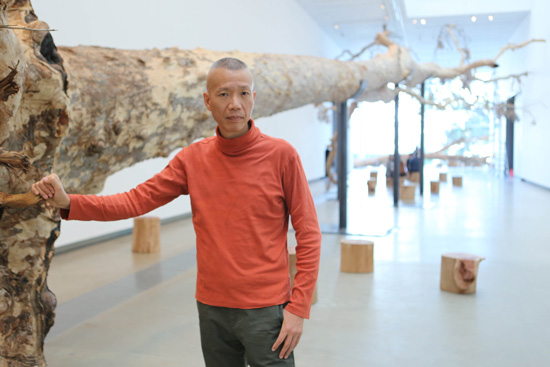

Cai Guo-Qiang in front of installation Eucalyptus at the Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia, 2013. Photo by Yuyu Chen, courtesy Cai Studio.

His first planned work, For the Asia Pacific Triennial, in 1996, ‘Dragon or Rainbow Serpent: A Myth Glorified or Feared – Project for Extraterrestrials no.26’ was unceremoniously cancelled due to an accidental explosion in the warehouse storing his fireworks and gunpowder. Three hydrogen balloons were intended to explode in the sky above the river, lighting a fuse that would writhe like a snake along the surface of the water. In a piece about this incident on the artist’s website, entitled “Be Careful of Fire’, he says, “Later, I retrieved the Queensland Art Gallery curator’s burned suit jacket and the remains of videographer Araki Takahisa’s camera and displayed them as the installation Be Careful with Fire, part of Origins and Myths of Fire: New Art from Japan, China, and Korea, an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama, Japan.

For Cai’s second proposed work in Queensland three years later, he planned to sail 99 small metal boats in a curving line of blue flame down the river. The last boat in the line flipped over and the artist and the gathered crowd watched as one after one the boats sank beneath the blue flames to the bottom of the Brisbane River. After these two unrealised – indeed disastrous – projects, he may have felt that he had unfinished business in Queensland. ‘Falling Back to Earth’ (at GOMA until 11 May) consists of three monumental installations. Two new projects were inspired by his immersion in the Australian landscape and in his themes of humanity’s connection to the natural world. The third has a different resonance in an Australian context. ‘Head On’ was originally created for an exhibition in Germany, inspired by the dramatic, divided history of Berlin. ‘Heritage’, with its 99 replica creatures (polystyrene casts covered in hyper-real fur made from goatskin) gathered around a waterhole was inspired by Cai’s visit to the pristine environment of Stradbroke Island, and the fact that he considers Australia to be a kind of paradise. The title of the exhibition – his first solo show in Australia – evokes the traditional Chinese literati scholars’ yearning for nature and was inspired by a fourth century poem by Tao Yuanming. Why 99 animals? In Chinese numerology and in Taoist philosophy the number 9 is highly significant, representing completion, perfection and regeneration. 99 to Cai represents something that is yet to be completed.

This is the first time that the entire 3000 square metres of GOMA ground floor space has been given over to the work of a single living artist, and due to Cai Guo-Qiang’s global reputation international media – in particular Chinese language media – were targeted by the gallery, so expectations were high. ‘Heritage’ is the big drawcard and it is as spectacular as the gallery’s publicists would have us believe. There is a stillness that somehow transcends the crowds with their strollers and fidgety small children, and a feeling that you have entered a fairy-tale world where natural enemies can peaceably coexist. The enormous waterhole is surrounded by every conceivable kind of animal – zebras, giraffes, a horse, pandas, kangaroos, tigers, a lion, antelope – all creatures great and small. Their relative sizes and forms are exaggerated, enhancing the sense of unreality. They are rendered equal in their vulnerability as they drink, heads bent, from a huge pool of water. As you circumnavigate the pond, watching the animals and their reflections on the surface of the water, you slowly begin to think about the implications of this impossible scene. Cai has moved from the extra-terrestrial to the terrestrial, and invites us to think about our relationship with nature.

In ‘Head On’ 99 replica wolves appear as if in a freeze frame, arcing through the space in a graceful curve, only to hit the glass wall and slide to the floor, slinking back to begin the process all over again. In its original German setting this work had very particular connotations. Shown here, in conjunction with ‘Heritage’ it could be seen as an allegory of heroism, or as terrible misguided foolishness – a warning that those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it, perhaps. I thought about climate change deniers and the disastrous consequences of human decisions made in the interests of political expediency or short term greed. ‘Eucalyptus’ relocates a vast native gum, earmarked for clearing, to the gallery. Placed on its side it fills the architectural space and forces us to contemplate at close quarters its ancient, gnarled surface. Roots and branches stretch out like capillaries, touching the walls and inviting the visitor to walk underneath and look more closely at what we often take for granted. Cai visited Lamington National Park and was inspired by the giant Antarctic beeches and the primeval power of the landscape. Like the Chinese literati painters who found solace and a sense of the sublime in nature, Cai suggests there is both a moral and a spiritual dimension in our relationship to the land. We need to consider our place in the universe, our interconnectedness, and “fall back to earth.”