Campbelltown Arts Centre. They have a cafe that sells good strong coffee and plays Nina Simone. Looking out over the trees to the clouds, with the jazz music and the heat, we’re starting to doze…

Outside the galley there is a painfully thin man wearing a woman’s multicoloured, striped jumper. It might just pass for a man’s jumper but it hangs on his body like a wet towel slung over a chair. He’s wearing track pants – blue with sporty stripes – a pair of lady’s 70s sunglasses and he’s carrying a can of Jaguar rum ‘n’ coke. Trying to act nonchalant as walks round the car park he repeatedly points his finger as though he’s seen something interesting that needs to be singled out. He looks back. He looks forward. He points his finger again. But it’s all a fake. There’s nothing in the distance at all. It’s a simulation of an activity, a facsimile performed by someone who has forgotten the basics of normal everyday human behaviour. This guy may even get away with it sometimes but the girlfriend trailing along behind him blows the whole charade. She can barely keep her eyes open. The guy points again and glances back. The woman shrugs at him and says impatiently – yeah, yeah – and then stumbles on her thongs. Her eyes flick open for a moment, then slowly close again as she shuffles to the pedestrian crossing, her track pants sliding down her fat bum.

Change of scene and location. It’s GrantPirrie in Redfern for the opening of Todd McMillan’s show alone alone. McMillan’s work has been included in a lot group shows around town over the last couple of years and as we’ve seen more of his work, the more we’ve become convinced that he’s the real deal. His inclusion in shows at commercial spaces like Sherman’s and an upcoming gig at the MCA curated by Rachel Kent pretty much prove that we’re not alone in that assessment. Judging by the crowd at the GrantPirrie opening there seems to be a lot of good will towards McMillan and his suite of photographs and editioned DVD.

Todd McMillan, Oh Captain, my captain [dead albatross], 2005.

C type photograph, 120x84cms. Courtesy of the artist.

McMillan’s previous video works documented his performances and they had a rough and ready feel that added to their considerable charm. This somewhat shaky approach mostly works again for the artist. His use of a studio setting, some plastic Christmas trees, a bucket stolen from The Clock Hotel and a guest appearance by Tony Schwensen [and featuring the return of those eye watering shorts worn in Schwensen’s Performance Space show], all combine into an investigation of tropes from Romantic fiction and art. There’s The Rhyme of The Ancient Mariner, Casper David Friedrich, Henry David Theroux’s Walden and a tribute to lost boy poet Nick Drake. We wondered if maybe this time the works were done a little too quickly, perhaps too off the cuff, but one has to respect the perversity of doing something so fastand loose up against the icy beauty of the c-type print. We know that McMillan has the skills to pay the bills – as we used to say in the 80s – so we can only assume the whole deal is a deliberate short circuiting of the wide screen production values that this kind of subject usual enjoys. It’s Bill Henson meets stand up philosophy.

We had gone to see McMillan’s show knowing already that we were probably going to like it and we weren’t disappointed – it’s as strong a debut show as we have seen and doff our flat caps to GrantPirrie for giving him a go in the unpopular January slot which is usually reserved for group shows and Indigenous art. We had received an invitation directly from Zanny Begg to Mori gallery and the four shows all happening at once in the gallery space; Begg has a show called Glass Half Full in the small room, Adam Geczy has one wall of the big room for his Obituary For A Forrest and Black Sassy Collective and Huon Valley Environment Centre, Jai Critchley, Anna Belhalfaoui, Hanna Hildenbrand, Margaret Mayhew and Catherine Rogers have the rest.

We know, expectations are the killer of an open mind, but we went expecting to see a lot of pictures of trees and what we got were a lot of pictures of trees. Now it’s all very well to have a show to raise money for a good cause but it seems it’s impossible for many artists directly involved with those causes to rise above visual clichés. This is an image of a forest – we must save this forest – this art work is underwritten by an unassailable moral goodness – the end. Should we be complete bastards and mention that all these images attempting to save trees are printed on paper? It doesn’t matter because the cause is a sound and making a judgment based on the kinds of reasoning one takes to other art exhibitions would be wrong. So what if half of the Black Sassy Collective and Huon Valley Environment Centre work is actually some home made posters with stuck on text that look like school projects? Being in an art gallery is just a venue and it could just as well be a church hall or a local shopping centre.

Adam Geczy’s work attempts a much more sophisticated marriage of image and idea by placing large charcoal on paper drawings of trees – seen from the ground looking up – with photocopies of obituaries of recently deceased humans. It’s interesting to finally see a work by Geczy because until now we’d only read his articles and marveled at his books. For a guy with a major bugbear about Ricky Swallow’s work [and it’s alleged connections to sentimental fascism through the latter artist’s exemplary craft skills], we would have thought that Geczy would be a guy who could slam dunk Swallow in a WWE craft skills smack down. Not so. It turns out Geczy is just a so-so kind of artist when it comes to the craft of making an image on paper and the conceptual apparatus is about as obvious as it gets. Tree, looking up, deceased person, heaven, trees as individual living organisms, the irony of charcoal on paper – it’s all to much and yet, not enough.

The rest of the exhibition is a massive blancmange of images of trees of people protesting trees being cut down, some good, many not good. Among the Black Sassy Collective and Huon Valley Environment Centre work there’s a piece by Selena De Carvalho called Embers which features earth tones, a stuck on machine part, some furious cross hatching that looks like pipes and a big carbuncle like a livid eye. It’s teeny weeny – only 15cms by 7cms – and looks like a marquette for a huge installation for Ryde Civic Centre. We loved it. The triumvirate of Belhalfaoui, Hildenbrand and Mayhew promoted themselves prior to the opening of the show as a chance for people to come and see what art critics do in their sketch books and we can tell you it is mostly brown. Mayhew uses distemper and oil on linen [we had always thought that ‘distemper’ was sickness that some pets get, but we were clearly wrong]. Critchley is a guy who lives in a tree and Stephen Mori told us that he even gets his mail delivered there. We think that that is some sort of achievement.

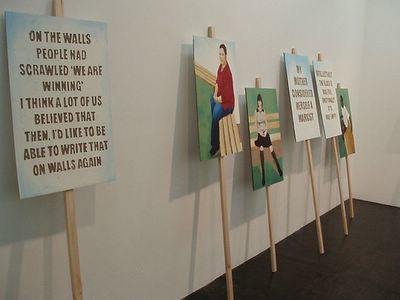

Zanny Begg, Glass Half Full, installation view.

Courtesy of the artist.

And so to the final room and Zanny Begg’s work. Perhaps alone in the whole show, Begg’s work had a very pleasurable and interesting reflexive quality, being as much about the social conditions of environmental campaigning and documenting individual responses as it was about the subject itself. Glass Half Full was a sequence of placards lent against the gallery wall with accompanied by ambiguous but suggestive commentaries:

Intellectually the glass is half full, emotionally its is half empty

On the walls people had scrawled “we are winning”. I think a lot of people believed that then. I’d like to be able to write that on walls again

It’s such a huge gap between here and there

I’m not sure I would write a slogan anymore

Next to each of these placards was a portrait, perhaps of the person who had made the comments, suggesting that there is a context for these activities outside the ‘issue’. The shadows in the portraits were rendered by removing the surface of the cardboard on which they had been painted to reveal the corrugated structure below. Maybe mentioning that these – and other works – had been painted on paper wasn’t such an act of bastardry after all? Indeed, the irony of this material playfulness is far more effective that Geczy’s laboured constructs. Begg adds in another layer with an accompanying zine that documents the personal history of environmental campaigners revealing that the characterization of those individuals as “professional protesters” or “rent-a-crowd” is an attempt to remove personal history – something far more provocative and meaningful than unfocussed group activity.

Ian Milliss wrote to us recently to tell us that we were “missing things” at “both ends of town”. We aren’t getting to all the shows, either in commercial galleries or in artist run spaces and it’s true, we are very lazy people. There was one show off our usual beaten track that we vowed we wouldn’t miss [and it’s on until November so the chances were good]. That show is City of Shadows at the Police and Justice Museum at Circular Quay and we managed to see it last week some 10 months before it’s due to close. [Actually, someone else told us that there isn’t a single art magazine in the country that covers museum exhibitions in places like the Historic Houses Trust or at the Australian Museum. We step confidently into that breach].

City of Shadows.

Courtesy Historic Houses Trust.

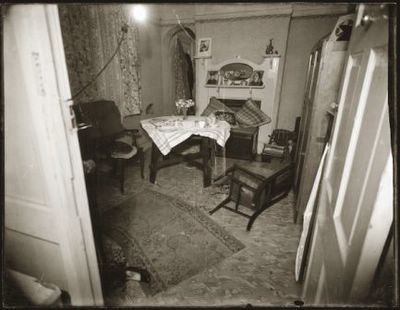

The attraction of the City of Shadows exhibition is that it’s a show of photographs from the archives of the Sydney police force dating from 1918 to 1948. Crime scene photographs fascinate us, their opaque, fragmented narratives and richly evocative settings remind us of a citynow almost completely vanished from the physical world. Going to the show we imagined that it would be just the photographs end to end, perhaps in several large rooms, and their dark magic would work its way into our minds. Instead City of Shadows is an exhibition with too much stuff and too little space. The curators have jammed what could have fitted nicely into Level 4 at the MCA or into a similar space at the Art Gallery of NSW into three galleries no larger than a small living room. The show piles photos one on top of the other illuminated from the rear by strip lighting. The walls are crenellated flats that we assume are meant to be modeled on Sydney’s inner city terraces and the third room is a long comic strip around a small room with additional photographs. It’s a general-public-friendly kind of set up quite distant from the more “art” oriented exhibitions that we are used to. It doesn’t demand too much of you and provides some nifty special effects where otherwise people might just get bored by looking at images.

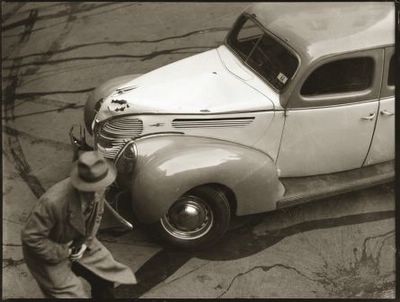

City of Shadows. Courtesy Historic Houses Trust.

Whatever the shortcomings of the available space, that there’s too much stuff in too small a space, and that the show was jammed packed when we went to see it, City of Shadows has to be easily one of the most fascinating shows on in Sydney at the moment. Divided into three sections – The Beat, Rogues Gallery and Dark Places – the show steps through three fascinating views of a lost city. The Beat are photographs of places where murders, disasters and human tragedies took place and is restricted to a stretch land called “The Horseshoe”, the suburbs immediately around Sydney starting in the west at Pyrmont and Ultimo, stretching south to Surry Hills and Redfern, then to East Sydney, Darlinghurst, the Cross and to the harbour. Rogues Gallery is a collection of suspect photographs taken in the course of arrests or investigations and Dark Places are crime scene photographs ranging from railway stations to bedrooms, from alleyways to public bars, from the water of the harbour to desolate vacant land.

The curators also created a three-screen video presentation with any accompanying voice over by curator Peter Doyle that is about as hard boiled Aussie cop as you could imagine. The videos brilliantly compile shots with a laconic description of the stories within. A large number of the images in the police archive have no accompanying information, so the detective work is trying to work out who the people were, where the shots were taken and what the investigations were all about.

City of Shadows. Courtesy Historic Houses Trust.

The Sydney in these photos contains trace elements of the city we know today. Indeed, many of the buildings are still standing and, despite gentrification, huge high rise building programs and the complete razing and rebuilding of Surry Hills, the eerie familiarity of the locations is disturbing and unsettling. What is even stranger are the faces of the people in the photographs. This is an Anglo–Irish Australia that no longer exists, perhaps a little familiar from family photographs of long dead uncles and great grandmothers, but these are images of an alien race of suited and hatted men, furred and jeweled women, well dressed gangsters, pimps, prostitutes and down-on-their-luck confidence tricksters. Their faces are open and smiling despite their misfortune. The Dark Places aren’t as dark as we imagined. For a public show in a public museum, we suspect that the worst images were held back but what we do see still holds a terrible aura. Using large glass plate cameras with a massive flash gun, the images in the video and on display in the galleries are ripe with exquisite period detail. Then there are traces of blood, an overturned chair, a dark black blood spatter on a door.

Which bring us back to Campbelltown Arts Centre. We were there to see Stars of Track and Field, a group show staged in the recently refurbished gallery. Why were we there? We’re not sure why the artist known as What has the ability to make us drive for a more than 3 ½ hours, but like the time we went to Wollongong to see his show in the regional gallery there, we were on the M5 heading south, listening to Bob Dylan on the radio and battling the rain.

The show has no theme – it’s just an exhibition of recent work by various artists and includes What, Brett East, Zehra Ahmed, Chris Firmstone, Hilton McCormick, Nigel Milsom, Sherna Teperson, Jaki Middleton and David Lawrey. It’s incredibly refreshing to see a show like this that lets the works speak for themselves. Hell, they don’t even have an essay, they don’t have a catalogue, and the room sheet is just some photocopied pages stapled together. The Campbelltown Arts Centre has apparently had $10 million spent on it, giving it a new lick of paint, some new carpet and a chance to show a bunch of artists usually only seen in ARIs with all the trimmings; lighting, air conditioning, wide open spaces to move around in, uncluttered sight lines. It’s almost like heaven out there.

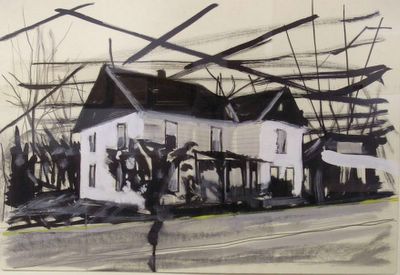

Nigel Milsom, Untitled, twin bedrooms, 2005.

Ink, graphite and gouache on matteboard, 65x90cms.

Courtesy of the artist.

We’ve mentioned Nigel Milsom here a few times now and we’re a bit reticent to sing his praises once again but put it this way – the promise that Milsom has been shown in recent outings at Phatspace and Gallery Wren has been bettered many times over with a selection of drawings and paintings that display a real maturity and deftness of touch. There are a couple of his stunning drawings of houses and one of a highrise, a couple of works that mix figuration with abstraction and they are very handsome indeed. We were most taken with Untitled [Evenings and Weekends], a series of ten framed sheets of A4, a police statement by Milsom concerning the death of a flat mate alternating with scribbly biro ink drawings of distorted faces, doodles and abstract lines. What could have been a ghastly and gauche gesture somehow comes off.

What is another commanding presence in this show. Last time we saw his work, he was doing some pretty out there conceptual paintings of the universe and footy legends and using bits of porno web sites to create books. He’s jettisoned all that for a new series of work using Liquid Nails, which is a kind of molten plastic that you squeeze out of a gun. Using a series of found picture frames with old images still intact, What has disgorged a whole lava flow of plastic goop and by doing so he’s created a lo fi indie rock that’s to Grunge art what Wolfmother are to Prog.

Brett East’s incredible, painstaking oil on canvas pictures of pills done in faux Flemish landscape compositions are indistinguishable from digital print composites he’s put together somehow using a computer called Vanitas. We can’t say with any honesty that we get exactly what he’s on about but another series called 6 Degrees of Separation appear to be some sort of negotiation between what an artist can do in a painting and the kinds of landscapes and interiors that are generated by computers. In a similar fashion, Chris Firmstone’s densely locked abstract acrylics on aluminum are hermetic universes and without a way in we’re still wondering what they’re doing.

There are no such confusions with Hilton McCormick’s big paintings. Apparently something of a cause celeb out in Campbelltown, McCormick had approached the Gallery asking for a show only to be shown the door by the Gallery’s old management. McCormick makes images in hand decorated picture frames of Jesus and friends from the Stations of the Cross with coloured lights affixed and an accompanying soundtrack [courtesy of a hidden tape player] which features Enya and the artist’s own voice reading from the Bible. The work’s sincerity and naïve stylings are so persuasive that you wonder what cruel hearted apparatchik would have turned him away. Happily these eccentric beauties are right at home in Stars of Track and Field.

Creating something of an odd echo of McCormick’s piece is the biggest and grandest installation we’ve seen by David Lawrey and Jaki Middleton. Called The Sound Before You Make It, the installation takes up one large gallery. When you walk in, a trigger sets off a strobe light from the middle of the room which has raised platform about eye height under a silver dome. Shadows from the strobe flicker on to the walls and you can make out men dancing. Then the music starts – the opening bars of Michael Jackson’s Thriller pounding away and then you see on the little platform hundreds of tiny Michael Jacksons and accompanying dancers dancing to the music with classic moves from the film clip. The strobe and the movement of the figures are timed in such a way that it really looks like the tiny figures are dancing rather than just whizzing around at about 24 revolutions per second. We ran out of the room, went back in, tried to edge close to the platform without setting off the trigger, but nothing worked. In the end, we just ran away.