Invited to speak at the Australian Art Industry symposium at Melbourne University, Andrew Frost reflected on a year’s worth of judging art prizes…

An email arrived in my inbox – an invitation to be a judge of the Blake Prize for Religious Art. I was flattered to be asked but not entirely surprised. And that was because of what had happened. Let me explain the background.

The email arrived about six months after the announcement of the Blake’s previous winner. There had been nothing controversial about the winner’s work but there had been a minor public scuffle over the selection process of the finalists. The selection process of the Blake involves three judges who individually select their list of finalists from all the entries received, and then, after those lists are put together and a long short list is made up, there’s a short short list. From that shorter short list a winner is chosen.

Although there are three judges, and there could have conceivably been a decision on finalists based on a simple 2 to 1 vote, the tradition of the Blake is that the judges should agree more or less on the selection of finalists and the winner. Consensus is a big part of the philosophy of the prize. The scuffle broke out when one of the judges refused to countenance the idea of a particular artist getting their work in as a finalist even though the other two judges wanted it in. The two judges decided to defer to the third judge and that artist’s work was excluded. What happened next was that after the process of finalist selection was completed, the two judges conferred and said, bugger it, we want that artists work in – and so it was. The third judge hit the roof upon learning of this development and he resigned from the panel before the judging was completed. A press release was written and dispatched. This resignation became public knowledge.

I knew the invitation was partly to do with my own small role in the scuffle. I’d written an opinion piece for The Sydney Morning Herald that basically argued this third judge was wrong. You could reasonably argue that the judge was entirely within his rights to say that he didn’t like the work and didn’t like the process and so on, but what I’d thought was absurd was his attempt to base this decision on some fairly spurious arguments about whether said work was religiously themed, and that in his view the artist was a charlatan anyway. The Blake Prize, as I argued in my op ed piece, is so liberal in its interpretation of what constitutes religiosity that an art work that might even be anti-religious was worthy of consideration. And indeed, worthy of inclusion.

When the invitation came to be a judge on the 2009 Blake I hadn’t at that point ever judged an art prize. How could you actually compare the artistic merits of different art works in a prize that ranged from painting to photography to video art to installation? What did it mean to be a judge exactly? And the thought of handing over $20,000 to one person seemed like a daunting idea – whatever it might mean for the winner there was also a question of how the validation of one art work against so many others might be viewed by the rest of the art community. What did it say about my discernment, my taste? And finally, there was the fairly major question of how I might react to religiously themed art given that my own Anarcho-Buddhist agnostic leanings don’t really hold up to objective scrutiny. When you’re dealing with someone else’s sincerity it’s probably best to handle with some care. At least with the Blake’s three judges there was a degree of cover – I could always blame someone else. So I agreed to be a judge and off we went.

That decision was the beginning of what has turned out to be more than a year’s worth of judging art prizes – a couple of student art prizes, a prize for emerging artists, an open-call art prize, a venerable art prize in a fairly unlikely location and I was on a selection committee for an art fair.

The winner of 2009 Blake Prize was Angelica Mesiti for a video work called Rapture [Silent Anthem]. If you haven’t seen the work I can describe it fairly simply – the video was shot from underneath the stage at a rock concert looking out at the faces of young people in the mosh pit. The video is a series of sequences of faces looking up to the sky, some in an attitude that resembles religious ecstasy, others as if writing in pain, many hands raised as droplets of water rain down on the slow motion action, the soundtrack completely silent. It’s about six minutes long and loops again.

When I saw the work I was pretty sure it’d be in the top five works for consideration as a potential winner. On the other hand, it did occur to me that convincing the other judges, the painter Del Kathryn Barton and journalist-broadcaster Stephen Crittenden, might be more difficult but they were already there ahead of me. The same thing happened for the Blake’s “emerging artist prize”, which we gave to another video work, Grant Steven’s floating mandala of text made from Facebook and Myspace status updates called ‘In the Beyond’. I walked away from my duties thinking that there was nothing to get upset about in the selection of winners or finalists. It was perhaps the height of naïveté on my part. As the short period between our decision and the announcement of the winner began I opened the Sydney Morning Herald on the morning of August 22nd and read the following:

Blake Prize Anti-Religious says Pell

FOR Cardinal George Pell, Australia’s leading prize for religious art is attracting work that is kitsch, anti-religious and sometimes only tenuously connected with spirituality.

The $20,000 Blake Prize will be announced next month, but the Catholic Archbishop of Sydney believes some of the work reflects religious ignorance and confusion more than thought and understanding.

He singled out a depiction of David and Goliath by the painter Adam Cullen, where the biblical figures are naked and deformed and David brandishes Goliath’s head, as ”gross”. ”It’s difficult to see how that is not anti-religious,” Cardinal Pell said.

Belinda Mason’s The Last Supper is a photographic portrait of the suspended Catholic priest Peter Kennedy, removed from his parish in Brisbane after allowing women to preach, using unorthodox prayers and blessing same-sex relationships.

Cardinal Pell criticised the artist’s depiction of Father Kennedy in a Christ-like pose. ”There is almost an element of kitsch about it,” he said. ”There’s no substance to it, but the church is not there to censor what I would regard as a deficient expression of religion.”

I had two almost simultaneous reactions – one was total incredulity that Pell had taken the time to look at the finalists, and the other was the distinct sensation one gets being a proud parent – look what my kids have done! Pell is like a quote machine. Any arts journalist wanting a conservative sound bite only need to wave some artefact of the contemporary world in his face and you get irony soaked statements that are both jaw droppingly funny and bizarrely unaware. As I showed the story to my wife I wondered what would happen when the finalists were announced.

And the reaction was fairly predictable. Christopher Allen denounced both the selection and winners in the pages of The Australian only briefly mentioning that it was he who resigned from the panel the year before while The Sydney Morning Herald’s John McDonald didn’t review the show at all as he seemed to be going through a year-long sabbatical from reviewing exhibitions of work by living artists. The rest of the media coverage was mostly centred on the fact that two video works had won the prize and that this was somehow significant. There was a great deal of talk online on religious media sites like the Catholic Weekly that tended to agree with Pell’s views.

The Blake experience I had in my first outing as a judge was essentially the art prize experience in microcosm. Prizes in Australia are generally divided into two categories, themed competitions either by subject or medium, sometimes both, or they’re competitions with an open call for entry. This second type of competition tends to be based around regions or cities, or even suburbs. Prize monies vary from a few hundred dollars, or goods in lieu of cash, right up to the $100,000 purse of competitions like the Moran. The audiences for the most high profile art prizes tend to be the most conservative and with the expression of public taste courted through popular “people’s choice” awards, canny organisers with a flair for a well-crafted press release can generate a vast amount of free publicity.

Awards are often developed and staged in response to a perceived lack of recognition for particular art forms, for artists at various stages of their careers or as a way to encourage such hard-to-define concepts as “creativity”. There are awards for video art, for small scale sculpture, for emerging artists, for communities, for ethnicities, for portraiture, landscape and genres, for particular themes and intentions, and many more besides. These are in my view developed with the best of intentions but also have a tendency to narrow the public recognition to the simple news cycle of who won what, for which art work, and for how much.

I was asked by a friend if the selection of the winner an art prize is “political”. I said I didn’t think they are. My experience has been that prizes aren’t overtly political in terms of the personal politics of who wins and who doesn’t, at least not if you disregard the notion of politics as being connected to factors such as the desirability of a certain art work for an acquisitive prize’s collection, or the potential for rogue judges with firmly held views, or any number of other extraneous factors weighing on the judging process.

But it would be another act of wilful naivety to deny that art prizes are not in themselves political by nature. The positioning of The Blake, for example, and the organisation’s careful cultivation of publicity for its aims, is both clear-eyed in terms of its intention, but also explicitly aligned philosophically. The prize exists as the celebration of a particular kind of viewpoint, a philosophy of inclusion, of equal time and an equality of voices, set against the more restrictive conservative positions of its critics. On that basis, the Blake, and just about all other prizes, has an inherent political position.

Art prizes have unavoidable effects on the careers of artists who win them. The higher profile prizes like the Archibald Prize for Portraiture are backed up a legion of gallerists ready to capitalise on the winning of the prize, hoping to cash in on that success, but it’s interesting to note that, according to sources, the Archibald prize adds little if anything to an artist’s prices. The prize money keeps them warm for a year or so, but the prestige of the prize isn’t something that can necessarily be traded. Given the media attention heaped on the artists who win, or are perceived as somehow controversial, trial-by-media is hardly a plus point to entering. The Archibald is regularly referred to as a circus of media and promotion, invigorated by the desire to capitalise on the highest profile event in Sydney’s yearly art calendar. Prizes like Contempora 5 with $100,000 attached can often seem like a good idea but the subsequent hassles afforded Ricky Swallow after he won it in 1999 at the age of 25 had more downside than up. The proliferation of prizes aimed at developing and exposing emerging talent, which on the face of it seems like a worthy cause, has become the art prize du jour, creating an even bigger disappointment when those aspiring artists hit 35 and have to look across that vast stretch of career desert called mid career.

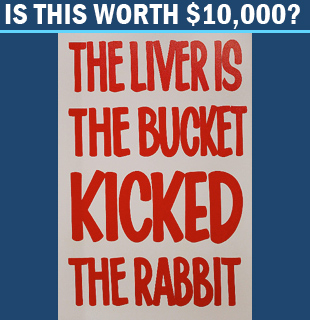

Of the six awards I’ve been involved in judging over the past 18 months, three awards went to video based works, two to paintings, and one for a sculpture. And that’s not counting the highly commended awards and runner up prizes that represented a much broader sampling of contemporary art practice including photography, drawing and installation. Amongst all that, the only story anyone seemed that interested in were those three video works. That was the news angle the Sydney Morning Herald used in its coverage of the Blake – video art wins religious prize. My most recent gig as a judge at The Churchie – a $10,000 open call prize for emerging artists staged in Brisbane –also went to a video work. At the announcement ceremony I had the rather unpleasant experience of being abused by a random member of the public so outraged that a video work should win she felt compelled to tell me that people interested in video art were out of their minds, and that if she had $10,000 she’d rather buy the TV set rather than the DVD art work. While the debate on whether video art is art is a non-argument in most of the contemporary art scene, it remains a hot-button issue in the minds of the public. Modernism is still controversial, and for those with a tiny grain of education in visual art, names like Duchamp and Baudrillard are interchangeable signifiers of for the high falutin’, head-up-their-arses dupes of contemporary art.

Art prizes have taken up the space left by the absence of the sort of wide spread private philanthropy found in the United States or in Europe where private foundations give artists opportunities to develop work, stage ambitious projects or conduct research. In Sydney, Kaldor Projects and the Sherman Foundation are the exceptions to this rule of absence but pale in comparison to say the Chicago-based John D. And Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and their ‘Genius Grant’ of $500,000 USD awarded annually to an anonymously nominated and selected collection of artists, writers, scientists, filmmakers, poets and bird fanciers.

It might be that the encouragement of such philanthropy through tax concessions and the like could be a way toward constructing some sort of meaningful patronage of the arts outside of direct government funding, and could even serve as major component of future federal government arts policy, but at this stage it’s hard to even imagine an Australian art world without its proliferation of prizes. The absence of an art philanthropy that is unconnected to existing museums, or to privately owned galleries which are in turn unconnected to the market value of the art on display is an eerie non-presence in Australia. One can barely imagine what a figure like Charles Saatchi might mean in Australia – and that too would have its downside – imagine for a moment that the late Kerry Packer had blown his millions on contemporary art rather than on gambling and then imagine how that patronage would warp and distort the art world as we know it. It might be that in that absence art prizes, for good or ill, are indeed the way we like to do things here.

Sport as a social and cultural activity is often used by the Australian art world as a stand-in for its opposite. You will no doubt be familiar with those press releases and newspaper stories that state the attendance numbers of a particular exhibition or annual visiting numbers to a certain museum outstrip the numbers at a grand final or a footy season. What is odd is about this construction is that for the art world art prizes and competitions are much the same thing as the sporting competition, albeit dressed up in some conceptual finery. Australian’s love a winner, and even more so when that winner represents something we aspire to. When a certain artist wins a particular award, and we happen to like that work, or their career thus far, it feels like a vindication of values rather than the more random process of judging art by fallible individuals. It‘s as though we need to believe in the rewarding of art as a “good thing”.

Thank you. A very interesting piece.

I feel that many artist compromise their work to fit within the parameters of a competition, and in the past have felt a tinge of guilt when painting a portrait of a ‘famous’ person for the Archibald, rather than painting a portrait because the subject has moved me.

You say that wealthy patronage might distort our world… I think that the competitions do this already.