From Luise Guest…

Was Nam June Paik, who died in 2006, an American artist or an Asian one? Or was he an early example of that newish phenomenon, the “global” artist, floating restlessly between different continents and cities? A show this month of Paik’s significant works at the Asia Society in New York, might suggest a re-evaluation of his position, placing him as a fore-runner of the explosion of Asian avant-garde art in the 21st century. The exhibition Becoming Robot rather suggests, however, that Paik was a kind of cultural boundary rider, an inter-galactic hitch-hiker. New York Times critic Holland Cotter describes him as an “existential floater”, a visionary more comfortable with sound waves and satellites than with any terrestrial matters. The man who fell to earth, perhaps. He is often described as “the father of video art” and certainly he was one of the first artists to see the possibilities of working with very new technologies in a post-Dada re-framing of the readymade.

Li Tai Po, 1987.10 antique wooden TV cabinets, 1 antique radio cabinet, antique Korean printing block, antique Korean book, 11 color TVs. 96 x 62 x 24 in. (243.8 x 157.5 x 61 cm). Asia Society, New York: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold and Ruth Newman, 2008.2. Photo credit: © 2007 John Bigelow Taylor Photography, courtesy of Asia Society, New York

I must confess a particular affection and partisanship here. Nam June Paik’s collaboration with cellist Charlotte Moorman was my introduction to the playful possibilities of contemporary art, and its debt to Duchamp, when I was a young art student. Who can forget a nude Moorman playing a cello made of Perspex TVs in the Art Gallery of New South Wales? Or wearing them, in ‘TV Bra for Living Sculpture’? And this at a far more prudish time, in 1976, when vice cops had only relatively recently removed copies of Michelangelo’s David from David Jones Department Store on a charge of public indecency!

‘TV Buddha’, also seen in Sydney in the 1970s (thanks to John Kaldor) and in other versions since, has always seemed to beautifully encapsulate his mix of seriousness and play; absurdity and moral purpose. There is a version here at the Asia Society and amidst more theatrical works, later readymades, and video footage from the 1980s (which does, it must be said, look seriously dated) it retains a compelling power and stillness. A closed circuit television camera and a seated Buddha figure face each other on a white plinth. The Buddha is engaged in silent contemplation of himself. Walk into the frame and you too become a part of the work’s circular navel gazing. Past and present, East and West, sacred and secular, stillness and busy-ness. A Zen wake-up call to mindfulness? It echoes Paik’s interest in Zen philosophy, shared with his friend and collaborator John Cage. Unlike some of the other works in the exhibition such as the roughly hand-painted TV sets of the artist’s late practice, charming though they are, ‘TV Buddha’ lingers in the mind.

The New York show provides a new context for these works, and adds a contemporary spin to all the well-known details of his life and work: the collaborations with John Cage and Joseph Beuys; the philosophies of the Fluxus Movement and the blurring of boundaries between art, performance, music and what was called “electromedia” back in the ‘70s, in those heady days of experimentation. ‘Becoming Robot’ suggests that Paik predicted the kind of world we now inhabit; our constant interaction with screens of various kinds, the relentless connectivity, the overload of information, and the tension between controlling technology and being controlled by it. Paik himself said, “Our life is half natural and half technological. Half-and-half is good. You cannot deny that high-tech is progress. We need it for jobs. Yet if you make only high-tech, you make war. So we must have a strong human element to keep modesty and natural life.”[1]

Transistor Television, 2005.Permanent oil marker and acrylic paint on vintage transistor television. 12½ x 9½ x 16 in. (31.8 x 24.1 x 40.6 cm). Nam June Paik Estate Photo credit: Ben Blackwell

Born in Seoul, Korea, in 1932, Paik’s family moved to Hong Kong in 1949 before the outbreak of the Korean War, and then to Japan the following year. He studied art and music at Tokyo University, completing his undergraduate thesis on Schoenberg. In 1956 he went to Germany, met John Cage and an extraordinary alignment of futurist thinking was born. Paik continued to compose music but began experimenting with performance and sculpture, working at the frontiers of experimental electronics including video, robotics, and (very primitive) computers. He arrived in New York in the mid-1960s and his irreverent approach to breaking down conventional boundaries between artist and audience, high art and popular culture, and art and science, immediately hit the zeitgeist.

The first work we see in the exhibition is the life-size, remote-controlled robot that he designed with electronics engineer Shuya Abe in Japan in 1964. He called it Robot K-456, a reference to a Mozart piano concerto. It’s a mechanical antique – charming like the Jetsons – a relic of a future long since past. Paik choreographed a performance for K-456 entitled ‘First Accident of the Twenty-First Century’. The robot walked along Madison Avenue and was hit by a car driven by a fellow artist whilst attempting to cross 75th Street, falling to the ground. Paik declared that this act represented “a catastrophe of technology” – a reminder that despite his geeky fascination for all things technological, his work is at its heart deeply humanist.

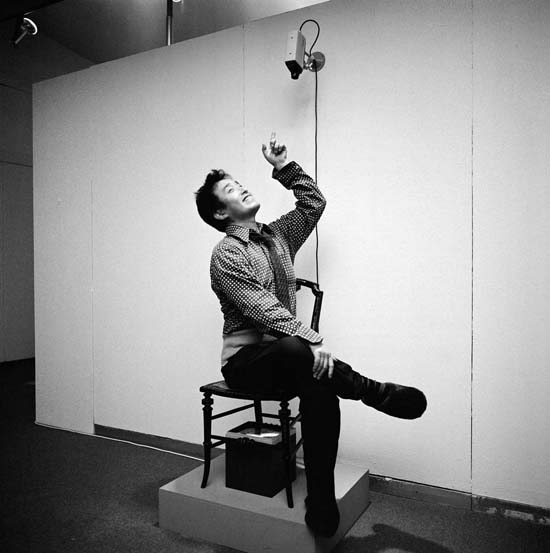

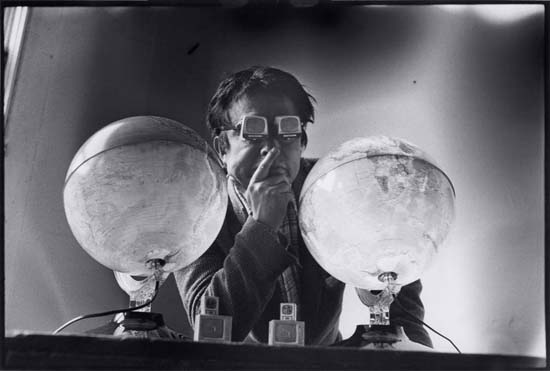

These early robots and machines are reminiscent of sculptures by Jean Tinguely, or the mad machines drawn by Heath Robinson. The humour is child-like. The sole purpose of ‘TV chair’ is to video-surveil the bottom of whoever sits on it. The artist as practical joker, Duchampian iconoclast. It seems so innocent. And redolent of a time when it was possible to think that art and fun were not diametrically opposed. Yet his imagining of ways to harness the possibilities of commercial television and multimedia is hugely significant. In a 1975 interview, he said, “Marcel Duchamp did everything except video. He made a large front door and a very small exit. That exit is video. It’s by it that you can exit Marcel Duchamp.”[2]Works such as ‘Chroma Key Glasses’ and ‘TV Penis’ are attachments to the body, revealing his interest in the possibilities of merging man and machine; artwork and audience. Nam June Paik would have loved Google Glass.

Paik sitting in TV Chair (1968/1976) in “Nam June Paik Werke, 1946–1976: Music, Fluxus, Video,” 1976. Photo credit: © Friedrich Rosenstiel, Cologne

The most engaging works for me, however, were his 1986 series ‘Family of Robot’, which presents us with Mother, Father and Baby robots, fabricated with vintage radio and television monitors. They suggest the extended hierarchical family of traditional Korean culture, and its emphasis on filial piety. In their child-like playfulness they are completely disarming. It is impossible to look at them without smiling.

What is revealed about Paik now, in this show, is how prescient he was. He imagined the possibilities of social media long before Mark Zuckerberg was born. He understood the possibilities of the internet. He invented the term “electronic superhighway.” He envisaged the creative potential of personal video and mobile phones. Paik’s work was highly influential in considering connections between technology and the body, and in the relational possibilities of technology, its potential for connecting individuals and communities. In 1971 he said, “People can create their own art and send it to their friends through video-telephone lines and elevate their mood by watching or attaching certain medical electronic gadgets and control their own brainwaves in order to achieve an instant Nirvana.”[3] His predictions have, by and large, come to pass, although he may not have imagined people using these miraculous inventions to share funny cat videos and pictures of their dinner. Numerous artists owe a debt to Paik’s restless experimentation and inventiveness, among them Stelarc, Mariko Mori, and most especially Cao Fei with her experiments in Second Life, and the invention of her own parallel universe, ‘RMB City.’

Sadly, it is Paik’s utopianism that seems quaint today, in an age of drones and the use of social media to foment terror; a time in which, despite our addiction to technology, we inevitably have a darker view. ‘Becoming Robot’ is a little like a window into a far more optimistic past, a reminder that art can challenge things we take for granted. Paik believed it was the duty of the artist to “reimagine technology in the service of art and culture.” Anyone?

Presentation of Good Morning Mr. Orwell, at the Kitchen Gallery, New York, on December 8, 1983. Photo credit: Photograph © 1983 by Lorenzo Bianda (Tegna, CH). The exhibition continues at Asia Society New York, 725 Park Avenue (at 70th Street) until January 4, 2015. The artist’s website, Nam June Paik estate

[1] Nam June Paik with Charlotte Moorman, ‘Video, vidiot, videology’ in Gregory Battock (ed), New artists video: a critical anthology, EP Dutton, New York 1978

[2] “Marcel Duchamp a tout fait sauf la video. Il a fait une grande porte d’entrée et une toute petite porte de sortie. Cette porte-là, c’est la video. C’est par elle que vous pouvez sortir de Marcel Duchamp.” Irmeline Leeber, “Entretien avec Nam June Paik,” Chroniques de l’art vivant 55 (February 1975)

[3] Nam June Paik, untitled essay reproduced in Sonsbeek 71: Sonsbeek buiten de perken (Arnhem: Sonsbeek Foundation, 1971)