Luise Guest on ‘Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei’ exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria…

Two ghosts loom over the bicycle frames, Lego bricks, Han Dynasty urns and screen-prints in Melbourne’s NGV. One is the spirit of Marcel Duchamp, who casts his long shadow over what we see there; the other is a spectral Mao Zedong. It must have seemed an inspired idea, to juxtapose the two giant figures of Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei: they each took the Duchampian ready-made and ran with it, making it (and themselves) into a new kind of global brand. Taking unexpected and irreverent positions on the world in which they found themselves, they each reinvented the identity of the artist in significant and substantial ways. Both were shaped by their arrival in New York, too, the gay boy from Pittsburgh, and the son of the famous Chinese poet. There are so many rich possibilities in bringing together two colossal figures, so significant to the 20th century and the start of the 21st. It’s a comprehensive overview of their work, featuring 200 works by Warhol and 120 by Ai. And yet…the exhibition disappoints in a number of ways.

Andy Warhol, Mao, 1972, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts. © 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

In part it is because Warhol and Ai Weiwei are just too damn ubiquitous. Obsessively recording every aspect of their daily lives (Warhol in film and Polaroids, Ai Weiwei on video, Twitter and Instagram), they democratised, appropriated, outsourced and demystified the practice of art like no-one else since Marcel himself. The result is, ironically, that in many cases the actual works have lost much of their power, reproduced just too often. The myth is bigger than the artworks: Nico and the Velvet Underground; a naked Joe Dallesandro and a fey Edie Sedgwick; Lou Reed at the Factory; cigarette smoke and crushed velvet, the apotheosis of cool. Ai Weiwei, undoubtedly brave and resolute, continues his crusade against the repressions of the Chinese regime: 181,000 followers on social media joined his ‘#flowersforfreedom’ campaign for the return of his confiscated passport. He has become a global superstar of dissidence. And yet… as I wandered through the NGV exhibition, I pondered why it fails to provide quite the anticipated big bang.

There are memorable moments. The installation of steel bicycle frames that soars in the foyer, glinting in the sun, makes us remember that Ai Weiwei’s earlier works were often poetic and multi-layered. The frames of the famous ‘Forever’ bicycle brand of his Cultural Revolution childhood are stacked in a spectacular tower. These bicycles are going nowhere, in a sardonic jab at both revolutionary socialism and the overwhelming scale of Chinese manufacturing. At the same time, they memorialise a 1960s Chinese childhood that is gone forever, much as his famous ‘Sunflower Seeds’ referenced a humble snack shared in very lean times. The dismembered feet of ancient Buddha statues, almost lost in the corner of a hectic and self-consciously over-designed space, remind us that much of Ai Weiwei’s work has focused on the destruction wrought upon China in the name of revolutionary ideology, ‘progress’ and modernisation. An installation of traditional wooden stools (a smaller version of the 886 shown at the Venice Biennale in 2013) continues his use of ancient artefacts as found objects. Like many other contemporary Chinese artists in the 1990s and early 2000s, Ai began to incorporate previously forbidden elements of traditional culture into his work, addressing the big questions of what we value, and why. The simple three-legged stool, once owned by every family and used for a multitude of purposes, has been superseded by mass-produced plastic.

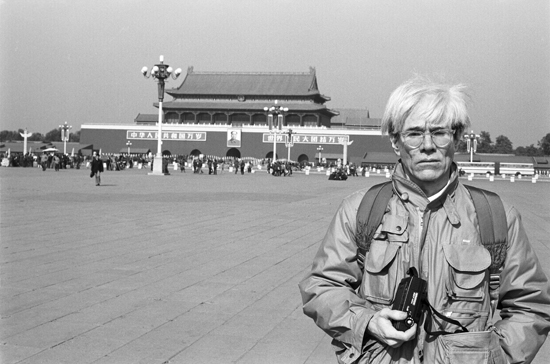

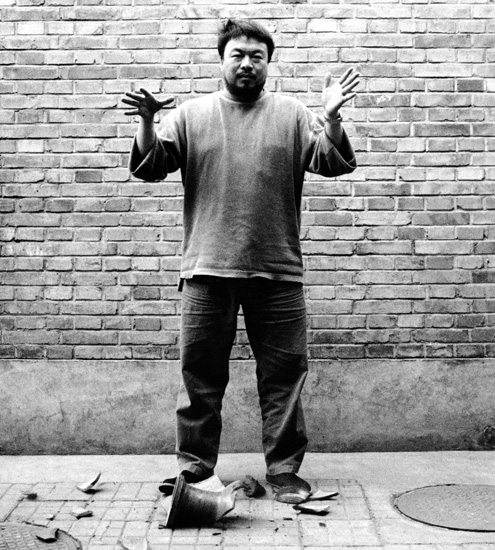

Christopher Makos, Andy Warhol in Tiananmen Square, 1982. © Christopher Makos 1982, makostudio.com

Surprises and moments of wit are woven amongst the familiar images, although some might argue that the famous ‘Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn’ photographs re-made in Lego are entirely too self-referential, and the portraits of human rights activists made with knock-off Lego are, sadly, as insubstantial as one of Ai’s tweets. Two walls are papered with images of the flower-filled bicycle basket outside Ai’s Beijing studio. He placed a bunch of flowers for every day that the Chinese government refused to return his passport after his release from 81 days of detention in 2011. The bicycle itself is propped against the wall in a mute symbol of resistance – and resilience.

A field of white porcelain flowers evokes the past suppression of individual desires and aspirations into the collectivist masses. Unfortunately, the exhibition text for this work refers only to the artist’s ‘Flowers for Freedom’ campaign, reducing it to a slogan. ‘Blossom’ is far more nuanced and multi-layered, referencing Chinese history, and Ai Weiwei’s own story. In the ‘Hundred Flowers’ campaign of 1956, Mao invited criticism of his policies with the dictum, ‘Let a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend.’ A year later, those who had accepted the invitation to express their views found themselves targeted in a purge. Up to 550,000 intellectuals, artists and writers were publicly discredited, some sent into exile and forced labour. Ai Weiwei’s father, Ai Qing, was one of these. The fragility of porcelain, that most Chinese of materials, testifies to the courage of those who spoke out.

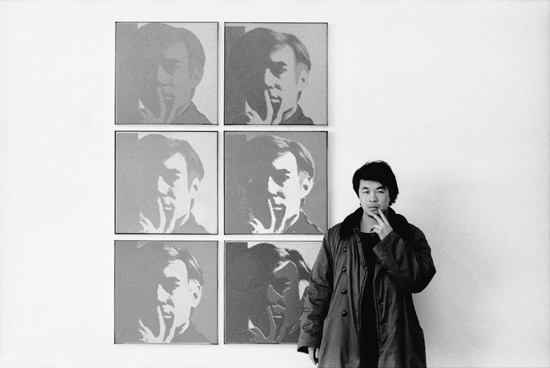

Ai Weiwei, At the Museum of Modern Art, 1987 (detail), from the New York Photographs series,1983–93, collection of Ai Weiwei. © Ai Weiwei

There is a marked shift in Ai’s practice. Early works, inspired by his discovery of Duchamp. Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, are playful and witty. The ancient urns turned into ‘assisted ready-mades’, the ‘safe sex’ raincoat with a condom drooping between its buttons (created at a time when so many young men were dying of HIV/Aids in New York) still appear fresh and interesting. We sense his excitement, like that of so many other Chinese artists, emerging from 30 years of Soviet Socialist Realism and discovering the world outside. After the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake, in which so many children perished beneath the rubble of their poorly constructed schools, Ai found the focus of his rage: government secrecy and corruption. Some of the most compelling viewing in this exhibition is the video footage shot by Ai and his friends at this time. Ai himself divides his practice into two periods: before and after his discovery of the internet. His particular genius has been to harness the forces of social media, in the process rather turning himself into an artwork, just as Warhol had done before him.

Apart from the truly iconic Brillo boxes, the most interesting of the Warhol works are always, to my mind, those in which his darkest demons emerged from behind the celebrity glitter: the electric chairs, the skulls, the guns, the Kennedy assassination imagery. Peter Schjeldahl, writing in the New Yorker, said, ‘The conflations that Warhol visited upon art – chiefly between painting and photography, and between handmade and mechanical reproduction – were like little technical threads that, when tugged, unravelled any received sense of what artists are and do.’ My major issue with the NGV exhibition is its obviousness: Ai Weiwei’s field of porcelain flowers is juxtaposed with Warhol’s screen-printed flowers; Warhol’s Coca Cola bottles with Ai Weiwei’s early ready-mades. There are more interesting connections to be made between these two polarising and complex figures, each of whom has ‘unravelled’ our understanding of the role of the artist.

The exhibition could have examined the dark mid-century anxiety lurking behind Warhol’s love of glamour and fame. ‘Buying is much more American than thinking,’ he said, ‘And I’m as American as they come.’ Such an exhibition would have made more sense of Ai Weiwei’s paradoxical and absurd combinations of tortured Qing Dynasty furniture, his (maybe) Han Dynasty urns dipped in household enamel, his palpable sense of loss when he saw the changed China to which he returned in 1993, after so many years on the fringes of New York’s artworld. From hobnobbing with Alan Ginsberg in the East Village to a grey, industrial, transforming Beijing – what a shock that must have been. This rupture echoes the trauma of his childhood, when his father, Ai Qing, was exiled. The great poet, who had stood with Mao on the podium when the Communists claimed victory in 1949, was forced to dig latrines in the poverty-stricken far reaches of Xinjiang Province for years, forbidden to write. These bitter experiences formed Ai Weiwei, and they inform his implacable hatred for the injustices he now perceives in China.

Ai Weiwei, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995 (detail), collection of Ai Weiwei. © Ai Weiwei

In 1982 Warhol encountered a China just emerging from the Cultural Revolution. Chinese artists were beginning to express their conflicted responses to the brave new world of mass production and avid consumption they were entering, with a sardonic Pop-inspired sensibility. By this time Ai Weiwei was living in New York, obsessively recording the gritty urban melting pot of the East Village, cultivating a persona of Warholian cool. The first book he bought in English on his arrival in America was ‘The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (from A to B and Back Again’. Their relentless photographic documentation of the everyday provides a wonderful, and often moving, documentation of an era: Warhol with Stevie Wonder and Grace Jones; Ai with Xu Bing and Wang Keping, all three looking impossibly young; with Allan Ginsberg; or posed in an early version of the ‘selfie’, in front of Warhol’s multiple self-portrait. One photograph records an East Village Housing Protest in June of 1989. I realised with a shock that at that time Ai Weiwei saw the TV coverage of PLA tanks entering Tiananmen Square. The installations of ‘Forever’ brand bicycles that he began to make in the early ‘90s, grown larger and more monumental in scale over the years, may also be read as a reference to the crushed bicycles left in the aftermath, mute testament to an event almost entirely erased from the historical record inside China.

The verdict? As a historical document, this exhibition is absorbing, but I was left with an uncomfortable sense that the desire for a blockbuster triumphed over a more nuanced investigation of the artists.

Andy Warhol – Ai Weiwei is at the NGV International, Melbourne, until April 24, 2016