Luise Guest talks to Ouyang Chun about his work, career and latest exhibition…

In a long conversation at his Beijing home and studio last month, Chinese artist Ouyang Chun spoke about his life and how he developed his most recent body of work for an extraordinarily ambitious solo show. This exhibition, ‘The Mortals’, at the prestigious ShanghArt Gallery, on Shanghai’s ‘museum mile’ of the West Bund, featured installations and sculptures made from junk salvaged from the staff living quarters of Xi’an University of Technology, where the artist had once lived with his parents. The compound was about to be demolished, so Ouyang made three trips from Beijing to Xi’an and collected almost 12 tons of rubbish and household goods. From toilet seats to timber doors and windows, from thermos flasks and crockery to rusty bedsteads, battered suitcases and broken furniture, for Ouyang every object was imbued with traces of time and untold histories. This collection of unloved and forlorn things unsealed his memories of a time when he too felt forlorn and forsaken.

Born in Beijing in 1974, Chinese artist Ouyang Chun’s life trajectory was forever altered when his father’s entire university was sent from the capital city to Xi’an in the early 1970s, some time after the establishment of the ‘Third Front’, Mao Zedong’s 1964-71 program developing a self-sufficient industrial base in south-west China in case of war. A sense of being locked outside the inner circle has haunted the artist, who is one of very few successful post-1980s Chinese artists to have been essentially self-taught. In a Chinese artworld where the academy with its traditions and networks of guanxiremain very powerful, Ouyang developed his own idiosyncratic painting style and a sculptural practice grounded in the collection and reinvention of discarded objects and rubbish. As a rebellious university dropout Ouyang wandered the back streets and semi-rural outskirts of Xi’an, collecting the detritus of society, transforming the things he rescued into quirky sculptural pieces.

On a recent sunny afternoon in the Beijing artists’ enclave of Songzhuang, while the artist’s daughter quietly refilled our teacups I asked Ouyang to tell me about his boyhood, as a displaced Beijing boy growing up in Xi’an. He said:

“Well, I will tell you the story about my family. My father was a professor at the university, originally located in Beijing, and later the university was moved to Xi’an because of some political issues at the time – a lot of research institutions and educational institutions were moved to somewhere else other than Beijing. And, actually, we were preparing for a war against the former Soviet Union. And my father met my mother in Xi’an … And in Xi’an we felt really isolated, we could hardly connect with the local community because Beijing was a totally different world from Xi’an – we felt like we were living on an isolated island.”

Ouyang Chun was a solitary child, and memories of feeling adrift in a crowd recur in his work: “Of course, my childhood was lonely; although I had some friends, spiritually I often felt isolated and the impact lasted until today and it also influenced my artistic practice and my personal development.”

He missed out on his preferred university course and instead enrolled in a two-year College Diploma in art education, but Ouyang preferred to spend his days painting by himself in the countryside. ‘I would say the art education in China is poisonous,’ he said, emphatically: ‘Really, really!’ After some years of aimless drifting he returned to Beijing and finally established himself as a professional artist in his late twenties. This complicated and unusual (in a Chinese context) life experience has predisposed him to appreciate broken, abandoned things and to understand and value marginalised or ‘left-behind’ people in a world of constant social upheaval. Speaking of the materials he used for his assemblages and installations in ‘The Mortals’, with their strange mix of humour, nostalgia and sadness he said: “The reason I returned to that place and picked up things is because, well, I think everything there is very precious … They contain my memory of childhood. They contain, I would say, the hearts of the intellectuals and the beauty of the time, and the stories at that time. And there is a lot of strength and spirit we can find in those things.”

Across different levels of the gallery space in Shanghai, Ouyang Chun created a world of ‘mortals’ and their memories. He constructed every work himself in situ: nothing was pre-assembled, and the component parts of each work are painstakingly stacked and piled, weighted and counterbalanced, some appearing more precarious than others. You first look over the gallery floor from a viewing platform, before traversing sections that represent ‘river’, ‘nature’ and, finally, religion’, where you find a towering stupa made of discarded, weathered timber.

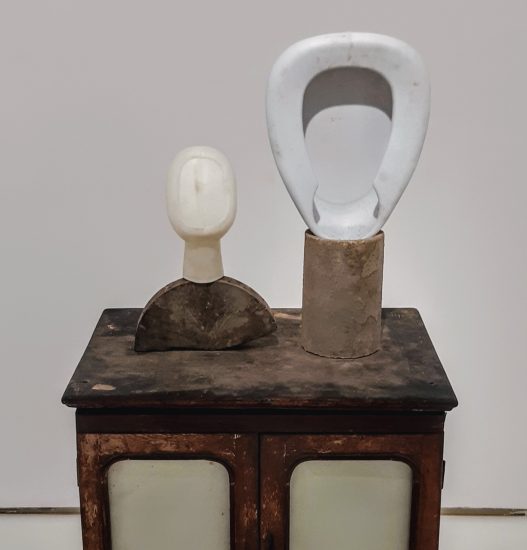

On the second floor, smaller works recall family histories and social identities, including ‘Papa’, ‘Concubine’, ‘Woman’, and ‘King and Queen no. 1 and 2’. These works convey a sly wit as well as a sense of melancholy – and also reveal the artist’s deep knowledge of modern and contemporary sculpture, from Constantin Brancusi and Henry Moore to Sarah Lucas. In King and Queen No.2, for example, the royal pair are made up of an inverted bed pan and another medical device that resembles the stylized head of an ancient Cycladic figurine – or, perhaps, a work by Brancusi. Mammothhas legs made of buckets and enameled pots and pans; its body is a sagging old mattress and suitcases bound with rope and a hose that may once have been attached to a washing machine becomes the animal’s trunk.

Endlessly inventive and often very funny, there is also a deep melancholy in these works, most evident in Thousands of Songs, a circular mosaic of cooking pots, china bowls and enamel dishes laid out on the floor around a circular table draped with a dirty, torn table-cloth. Where are they now, all these families of intellectuals banished to the provinces who once gathered around dinner tables in Xi’an? The Mortals memorialises the lives of countless Chinese citizens who were sent far from home in the service of the Motherland. It is also a testament to their resilience and courage.

About the artist: Born in 1974 in Beijing, Ouyang Chun was raised in Xi’an, where his father had been sent along with other professors to the Xi’an University of Technology. He studied briefly for an art education credential at the Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts, but he considers himself essentially a self-taught artist. Working across many media and styles, from idiosyncratic expressionist painting to assemblage and bronze sculpture, his work has been shown in solo and group exhibitions within and beyond China, including in Indonesia, Germany, Austria and the UK.

About the author: Luise Guest is the Manager of Research for the White Rabbit Collection of Contemporary Chinese Art in Sydney. She interviewed Ouyang Chun in Beijing in April 2019 for the Judith Neilson/ White Rabbit Collection Archive, before viewing the exhibition ‘The Mortals’ at ShanghART Gallery, West Bund, Shanghai. One of the works described in this article, ‘King and Queen No. 2’ is now held in the White Rabbit Collection.