In advance of the opening of Rodney Pople’s new series Shell Shocked at [>] Australian Galleries in Sydney, Andrew Frost‘s full and unexpurgated essay for the show tackles the controversial painter’s take on the mythology of ANZAC…

Like many towns and cities across Australia, some of the older streets in my neighbourhood are named for significant World War One battles. One such street – Lone Pine Avenue – commemorates a battle in 1915 during Australia’s ill-fated Gallipoli campaign. Under heavy fire, Australian troops surged forward across no man’s land and captured Turkish trenches. Despite incredible bravery, that resulted in the awarding of six Victoria Crosses, and the most awarded in any single action involving Australian troops during the war, the soldiers were eventually driven back with 2,300 either killed or wounded.

Egg tempera on linen, 200cm x 283cm

Lone Pine Avenue itself is unremarkable. It’s a long strip of suburban housing that runs out at the foot of some bush covered hills, and at the other end where the avenue meets the main road, there’s a down-at-heel strip mall which includes the Lone Pine Takeaway, a chemist, that aside from the usual medicines and shampoos, also dispenses methadone, and a small supermarket and bottle shop that’ll put purchases on tick. I learned recently that one of the local real estate agents/land developers who were responsible for subdividing the area had served in Gallipoli, and had taken a photo of the infamous pine tree. Happily, he also survived the war, and went on to name the avenue with suitable patriotic reverence.

The historian Benedict Anderson coined the term ‘imagined community’. That is, the shared consciousness of a population, a political and ideological grouping that, among other things, tells stories in order to imagine itself into being. Communities, argued Anderson, are not distinguished by whether the stories that are told are real or not, “…but by the style with which they are imagined” [1].

In Australia, the stories of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps [ANZAC], and certain aspects of the country’s involvement in WW1, form one of the central components of Australia’s national identity. We take the ANZAC story very seriously. ANZAC is invoked for soldiers serving today, but also for sportspeople representing Australia, lifesavers at the beaches, and for battlers who embody its spirit fighting bushfires or surviving floods. We police how that story is told: laws exist that limit how commerce can associate itself with ANZAC and how and where the acronym can be used. Beyond the law, anyone who publicly questions the ANZAC mythology in the media is shouted down and excluded. Since suburban war memorials have long since become anonymous due to their sheer ubiquity, and membership to the local RSL club is these days just a matter of your street address, the mismatch between the reality of life as it’s lived and the underlying mythology of nationhood, is as obvious as the strange disjunction between the symbolism and the reality at the corner of the Lone Pine Avenue just a few kilometres from my home.

Rodney Pople has cast his eye across the ANZAC story and found there a history of untruths, a selective telling that adheres to the dominant national narrative where Australia finds itself at war, not because of invasion but out of loyalty to the mother country, then defeated and in retreat from Gallipoli, but eventually victorious as part of the allied effort. Despite the disaster, this is also where the fundamental elements of Australian masculinity are said to be forged – the qualities of resilience, fortitude, and mateship. For Pople, the story is also a calamity, first in the reality of the savagery of warfare, but also in the absurd and politically opportune revision of the ANZAC experience into a strict conservative orthodoxy. Where most artists, official Australian war artists and others, have approached the story with deference and respect, Pople has taken a different route, creating what is in essence an imaginary history.

Oil on linen, 95cm x 131cm

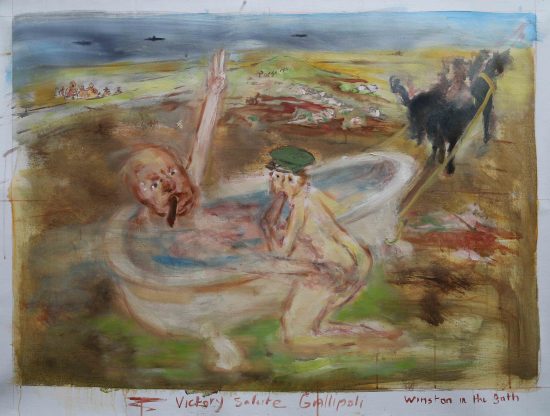

Pople’s Shell Shocked series takes place within a variety of settings, from fragmentary and ghostly landscapes as if conjured from collective memory, to the galleries of art museums, and the Australian War Memorial [AWM] in Canberra. Like much of Pople’s previous work, there is a dark streak of satire in the major paintings and smaller companion works. Where the artist has previously taken on subjects such as class, art history and disturbing contemporary events such as the 1996 Port Arthur Massacre, with a frank and uncensored approach, here too the ANZAC legend is portrayed in part in an often-profane sequence of images. The subservience of Australian troops to imperial British command is rendered as a series of sexual acts such as in Churchill in the Bath Gallipoli 1915[2018] where the architect of the allied defeat is fellated by a solider, or in War Memorial 3[2018] where an orgy takes place in the AWM’s outside gallery of remembrance atop the plinth of a war memorial. Elsewhere, ‘great men’ – leaders and generals are treated with disdain, a mockery of position, privilege and their ultimate unaccountability for the atrocity of WW1. Sick of the glorification of war that followed the conflict’s recent 100thanniversary, Pople uses the rudeness of these images to overturn the absurd cant of the ANZAC mythology, and to humanise the story, both for the people who were there, and for the audience of these confronting images.

Egg tempera on linen, 205cm x 255cm

The way in which these works were produced marks an interesting departure. Although he is not a painter who habitually makes expressionless realist pictures, Pople’s paintings have tended to feature ‘finished’ surfaces that create a tension between their illusionistic quality and livelier, painterly surfaces. In Shell Shocked, Pople has foregrounded a much reduced approach, akin to drawing, working with oil, and tempera, either on linen or plywood. War Hero [2018] and Welcome Home[2018] are the connective links to his previous paintings, their dark backgrounds serving to focus attention on foreground subjects. But other works reject this approach, paintings such as in General or Poet, Hamilton at Gallipoli[2018] which isolates its central figure by painting in around the rider and horse, but the picture falling away into a sketchier incompleteness at its edges. The artist suggests that this method of working is analogous to his nervous system, an urgent gesture that jumps from brush to canvas, reinforcing the singular nature of the image’s message, as though time is of the essence and the things that should said, must be said without delay.

In the research for this series of pictures Pople chose not to use any historical photography, drawings, or paintings as reference. Instead, he immersed himself in text, histories, biographies and diaries from WW1, and along with visits to the AWM, he built a sense memory of the key figures, events and places that together form this alternative history.

Pople is an exceptionally literate painter, often quoting or appropriating elements of other artist’s work for his own, his reference points ranging across art history for pictures that reproduce in part or almost whole, including paintings by Thomas Gainsborough, Francisco Goya, and George Stubbs, among many others.

In this series, Pople has drawn on contemporary artists including Anselm Keifer, whose paintings of long hallways and rooms from a front-on perspective can be detected in Pople’s renderings of the AWM, but also elements of the German artists images of war, particularly the recurring motif of battleships, here used by Pople as devices to literally punctuate the already marginal sense of painterly realism, such as the ship crashing through a wall in War Memorial 1, the aircraft buzzing through the War Heroes Memorialand the ambulance in War Memorial 3 [all 2018]. The treatment of figures, the spidery text and absurd sex acts in the images also recall the work of Chilean-Australian painter Juan Davila, while the influence of British painter Francis Bacon can be found in a variety of ways, notably in Pople’s use of light. The legacy of Sidney Nolan, a painter of war images but never officially a ‘war artist’, hangs over these works too – his presence quoted in the background figures and rider in Returned Soldier[2018]. But despite this range of references, these works remain Pople’s own, their acerbic humour, and frank despair, trademarks of the artist’s worldview.

Egg tempera on linen, 200cm x 280cm

Pople is of the belief that it is the role of the artist to question things. It’s not enough to produce pleasant images, or to even take on serious subjects if their treatment aligns to easy public sentiment. At a time when art struggles to find relevance, individual genres within painting seem virtually exhausted – what is the point of painting the landscape, asks Pople. And indeed, what is the use of speaking if you’re not speaking the truth? There have been a number of recent Australian artists who have painted on the subject of WW1, and on ANZAC, but they have demurred when it came to tackling the nature of war, and the self-serving lies told about it. Pople stands virtually alone when it comes to saying the unsayable, and both experience the same kind of reprobation as anyone that speaks out against the national mythology.

Internationally, many artists and writers, filmmakers and playwrights have produced stunning indictments of conflict, from the nationalist fervour that drives us to war, to its considerable cost, yet Australia’s visual legacy of anti war sentiment has remained slim. One of the best known popular works on WW1 is Peter Weir’s celebrated film Gallipoli [1981], a virtual hagiography of the ANZAC myth, where the sacrifice of individuals rests, ultimately, on a sense of duty to mateship, even before country, or cause. While I feel some sympathy for that view, the assumption of ANZAC as the foundation of conservative Australia over the last two decades has been used to mobilise popular sentiment into dubious alliances in wars of questionable purpose, all of this happening while the push to recognise Australia’s historical wars against its own Indigenous people has been treated as a fringe political cause.

Rodney Popleoil on linen, 103cm x 143cm

In this context the Shell Shocked series Whas real urgency, Pople’s paintings a vehicle for a sincere questioning of more than a century of myth making. Of his paintings Pople tells me that he did them because it “needed to be said given what is happening in the world now” – the breakup of old alliances, the erosion of democracy and the rise of militarist, right wing nationalism. Through a confronting mixture of metaphor and literalness, Pople’s paintings provide not so much an answer but another way of imagining an old, familiar story. He does it through satire, but also through a profound honesty, the narrative of war condensed to a story of bodies flung together in conflict, the violence of the encounter both violent and often sexual. The power of painting says Pople, is that “…it’s right there in front of you and you can’t escape.”

The theorist of nationalism and the nation state Tom Nairn describes nationalism as the “…pathology of modern developmental history, as inescapable as neurosis in the individual” with each country sharing a “…capacity for a descent into dementia, rooted in the dilemmas of helplessness, thrust upon most of the world …and largely incurable” [3]. The streets of my neighbourhood are enduring another record summer, the hot tarmac of Lone Pine Avenue almost a liquid, rivulets of tar softening and running into the gutters, rather like the pitch black of Rodney Pople’s paintings*. I know I can’t be the first to wonder if Australia will ever wake up from its shared dream of an imagined, illusory nationhood and accept an honest reappraisal of its history, but the reminder that this is long overdue is always valuable.

*Since the writing of this essay in January 2019, the shopping mall described in the essay was the subject of an arson attack which destroyed a recently opened barber shop, and severely damaged other shops in the block. The mall is currently empty and fenced off from the main road.

References:

1. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities. 1986. London: Verso Books. p.6

2. Gallipoli, Dir. Peter Weir. 1981. Associated R&R Films/Australian Film Commission.

3. Tom Nairn, The Break-up of Britain: Crisis and Neo-Nationalism. 1977/2000. Altona, Victoria: Common Ground. p. 359.