Isobel Philip ruminates on the possibility of the studio any-space…

Justine Varga’s solo show Moving Out at Stills Gallery elucidates the quiet poetic of private space. Documenting her studio in a series of refined and minimal compositions, Varga plays at the edge of photographic abstraction.

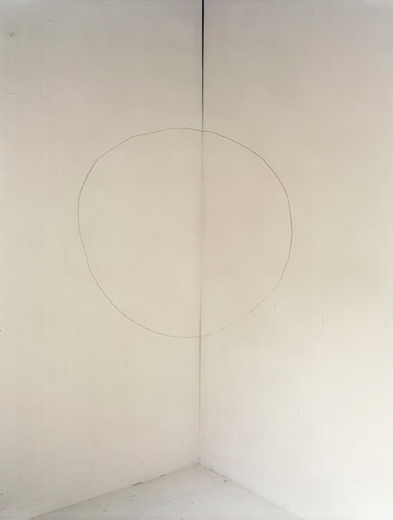

Justine Varga, Moving out #5, 2012. from Moving out, Type C print.

She stages subtle interventions that transform the space of her working environment into a study of form, suspending pieces of string and fragments of board against walls or manipulating the shards of light that pour into the room through an unseen window. This is a space that is open to alteration – a mutable space that is rewritten within each photograph.

But isn’t that precisely what a studio is? A site of pure potentiality? A place that facilitates production while resisting stagnation? An any-space?

Following this thought we become aware of how Varga’s photographs reach beyond the context of the personal and speak to the concept of the studio and its peculiar topographic conditions in broader abstract terms.

A studio is the place where an artist develops their work and their thinking, the site where they formulate their own aesthetic and conceptual scheme (their own ‘view of the world’ for want of a less clichéd phrase). It is the unacknowledged backdrop to an infinite number of projected realities – a doubled space where the physical collides with the imagined.

Justine Varga, Moving out #1, 2012, from Moving out. Type C print.

In photographing her own studio, Varga transcribes its inherent spatial dualism by encoding it within the compositional structure of the works themselves. She photographs doubled spaces. In each of her images we see two distinct yet contemporaneous spaces layered on top of one another. There is the space of the room with its physical parameters – its floor, walls and ceiling – but there is also another space that unfolds within the frame. This is a space with an invisible geography – a space that can’t be mapped – in which the string or the shards of sunlight seem to hang, suspended over the bare and empty walls of the studio. For indeed these forms – the string / the light – appear to levitate, occupying a unique spatial plane from that of the physical room.

This other space, inscribed and marked by the delicate arrangements of string and light, is projected out of the concrete space of the studio. Negotiating the interplay between these two spaces, Varga adds new dimension and conceptual weight to the phrase ‘moving out.’ In these images, where two distinct spaces are superimposed, we do witness a movement out: it is the movement across the divide between the real and the intangible.

The power of these works, for me at least, is not simply a consequence of Varga’s astute eye for arrangement and composition (not to mention the subtleties of colour and tone that I find particularly beautiful) but the way she uncovers and navigates invisible (and impossible) geographies. Revealing the space that hovers over the everyday and the mundane – the corner of a room, the edge of a floor – she gives form to the imperceptible.