We have of late been suffering from acute phonotony, that debilitating ennui brought on by too much photography. Although we had promised to review the Citigroup Private Bank Australian Photographic Portrait Prize at the Art Gallery of NSW we just couldn’t rouse enough enthusiasm for the job. Contemporary photography is, on the whole, very dull and although we recognise the artistry of creating glacially beautiful surfaces, it leaves us unimpressed and unmoved, struggling to tell the difference between artists and art and advertising. It all looks the same.

One of the current trends in contemporary photography is a tendency to quote the styles of advertising, to attempt a high gloss sheen that boasts big budget production values and edges the work towards the mainstream of everyday image making and reception. Looking recently at some photography hung in the window of a clothing store we were impressed by a shot of some nice kids in nice clothes walking down a street in what looked like a town in the old West. One guy was on a vintage motorcycle that looked like it was straight out of a Motorcycle Diaries. He rode alongside a group of teenagers who were walking purposefully forward a la Reservoir Dogs. Where were these kids going? Where they the Wild Bunch, well dressed revolutionaries who were going to take the fight to “the man” (as they would have in the mythical 60s) or were they on their way down the street to Starbucks? They weren’t going anywhere, were frozen in a moment of mysterious, impenetrable nothingness framed in the window of a shop that sold jeans.

We were reminded of this experience when we went to see Darren Sylvester’s debut show with Sullivan & Strumpf: Darren Sylvester: We Can Love Because We Know We Can Lose Love. Sylvester is another artist who attempts to create that high gloss sheen of contemporary art aesthetics that edges so perilously close to the empty rhetorical quotations of advertising. But unlike fellow Melbourne artists such as David Rosetzky or Adelaide’s Deborah Paauwe, Sylvester manages to pull off the production level to which he aspires. Instead of the hokey faux-Christian TV advertising look of Rosetzky’s work or the wincingly artistic execution of Paauwe, Sylvester’s work marshals cast, crew, lighting, makeup and costume into a flawless product that effaces its own production values in the quasi-serious quotations of emotional states described in the titles: Our Future Was Ours, Single Again, Your First Love is Your Last…

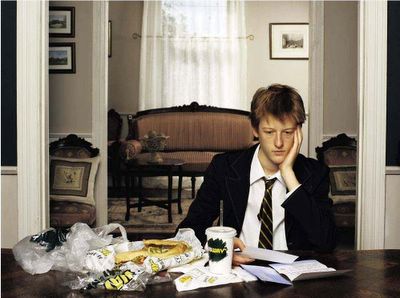

Your First Love Is Your Last Love, Darren Sylvester, 2004.

This is the “point of difference” with Sylvester. Instead of just reveling in what he has achieved and feeling comfortable that his work could easily sit next to the likes of Jeff Wall or Gregory Crewdson (albeit on a much smaller scale), Sylvester’s work wants to place some sort of emotional state into the captured, single frame narrative. Viewing the works without the titles is a remarkably empty experience. Your First Love is Your Last Lovefeatures a kid, the detritus of his after-school Subway snack on the dining room table of his upper class home and what is presumably the piss-off letter in his hand. He looks glum but dry eyed. Without the title you can more or less work out what is happening in the image but it’s a distant sensation. With the title, however, the whole narrative comes into focus and the evocation of a discernable emotional state is there.

So do we actually feel for this kid, or are we just enjoying the quotation of the feeling? For us it was a bit like being on drugs where you would swear that you really are feeling something but as soon as it wears off you know it was just the drugs talking. In Sylvester’s show, the emotion that’s apparently invoked is a fleeting parenthetical aside to the image. We don’t know if the works in this show were meant to be taken seriously as emotional statements or whether they are “emotions”, or if indeed they were engaging with the estrangement of feeling we routinely encounter when we see art and advertising this glossy and lavishly produced, but for once we knew what we really wanted at the Sullivan & Strumpf exhibition – where were the wall notes? We wanted someone to please tell us what we were meant to be experiencing.

The seven photographic works were accompanied by a video piece called Don’t Lose Yourself In Tomorrow, a four and a half minute loop. In the piece a young kid about 7 or 8 is seen in bed in his bedroom which is a shrine to Pokemon – Pokemon pyjamas, sheets, curtains, lamps and night lights – and he is sleeping. On a stool next to the bed is a Mac widescreen laptop from which spooky ambient music is heard and a screen saver pulses in time. Waking, the kid gets out of bed and looks out the window. He gets back into bed and as he falls asleep the image cuts away to the screen saver and then to increasingly manic looking close-ups of a Pokemon lamp, as though the Pokemon is sending the kid signals in his sleep. The kid wakes, gets out of bed and looks out the window – and so the loop goes around again.

As a title Don’t Lose Yourself In Tomorrow is a bit of a time warp in itself as no self respecting kid would be seen wearing Pokemon in 2005, but this is art, not reality. As a video work, the production values are amazing, the piece appears to have been shot on 35mm with dollies, tilts and pull focus and despite some heavy handed editing in the “spooky” bits and “tense” music, the effect is mesmerizing. But with the added element of duration, the ambiguity of the work – both in intention and effect – is less than enthralling. One reader commented here last week that Sylvester’s work is like Post Rock, like it is the thing but has a brainy, jazz-tinged self conscious edge.