The best thing about of this time of year are the commercial galleries who are bringing out some of their best shows for the penultimate spot in their exhibiting calendars. Esa Jaske has a corker of a double header opening on November 30 – Izabela Pluta’s Stills [Between], which are photographs taken in China of new housing developments that serve as a kind of companion piece to Richard Glover’s recent show at Tin Sheds – and Luke Crouch’s Dubplate Special – which looks like they may be painted vinyl albums done in a reggae stylee.

Conny Dietzschold Gallery opens a group show tomorrow night [Friday] to celebrate her 15 years as a gallerist and features an invitation featuring all of her artists in unflattering black and white. Ouch! In Melbourne, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image is opening an exhibition, Stanley Kubrick: Inside the Mind of A Visionary, which is the first exhibition in years that has made us even consider visiting Melbourne. Oxley has a show of Louise Hearman’s dark and moody paintings [and is, as you will no doubt recall, the artist that sent Benjamin Genocchio around the twist] and a mega one night only screening of TV Moore’s Across The Universe on November 30 at 50 Marshall Street Surry Hills.

Sherman Galleries has Glad Wrap Up – a group show featuring Peter Atkins, Dani Marti, Mel O’Callaghan, Lynne Roberts-Goodwin and Todd McMillan and in a completely unrelated event, Virginia Wilson, who uses her tiny Darlinghurst office space as an occasional gallery, has given Bill Wright full rein to curate Bleak Epiphanies: An Exhibition of Small Black Things, a group show of more than 30 artists opening December 1. Then there is Kaliman and his final show at his already ‘old’ gallery, The Kingpins Take Me To Your Dealer.

It’d be hard to imagine another artist or artist group hotter than The Kingpins right now. Yes, we know we vowed back in 2000 that we’d never use the word ‘hot’ in reference to anything but a sausage roll, but in this case it’s completely apropos. The opening last week was jammed with punters, the estimate of people just hanging around outside was close to 100. With a string of appearances in key museum shows, select overseas biennales and a pedigree of gigs in artist run galleries – not to mention the support of some key movers and shakers in the art scene – The Kingpins brilliant career has been on an upwards trajectory since they got together in 2000. Luckily for the group, the hype has been largely justified – their work has always been a crazy admixture of the sassy and the brazen but underwritten by a seriousness that sometimes felt oddly displaced in their showbiz razzamatazz. We were not alone in wondering what they would produce for their first commercial gallery show.

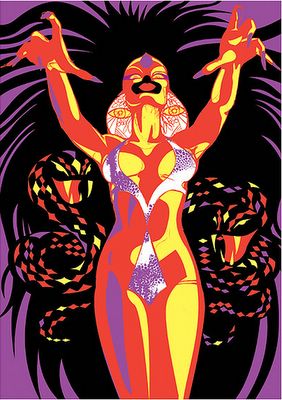

The Kingpins, Lookback, 2005.

When we’ve talked about The Kingpins in the past we’ve used the analogy that the four-member artist group being like a promising young band – they’ve had some club hits, a lot of radio play and then, we were hoping, they’d settle down and make a solid debut album. For their first show with Kaliman they’ve confounded expectations by skipping the debut album [and the just-like-the-first-one-follow-up-album, the-difficult-third-album and the-triple-live-at-Budokan-boxed-set], and have gone straight to the Greatest Hits compilation [with a bonus remix disc and posters]. Does the strategy work? Well, yes and no.

The group’s sheer chutzpah is so persuasive you’re entertained all the way. The gallery windows, painted black with cat’s eyes, takes you into the foyer plastered with black-on-green Darrel Lea style Take Me To You Dealer posters and a little space alien done up in K-Mart togs and a motorbike crash helmet – perhaps the alien asking to be introduced to Vasili Kaliman – called Turn Around Bright Eyes. In the front room there’s a black light extravaganza of gender confusing images straight out of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange with a dash of Leigh Bowery. The main room is a bit like being in Bing Lee – video monitors, garish neon signs, photos and info stuck to walls and headphones for private listening pleasure – a selection of props from old video shoots and a number of new DVD works clustered around the major work, Frank, a 14 channel piece.

The yes part of the show is in the individual pieces. The black light works in flock paper are outstanding – eye popping, garish and rude – and distill the idea of historical connection with the contemporary in a way that feels almost perfect. The video works are more problematic. Frank is so large and diffuse, it’s a little hard to tell what’s going on and with the sound track down low when we visited, it was a more mysterious experience than what the artists probably intended. The more intimate headphone listening DVDs worked much better. 30 BPM featured the Kingpins chucking New Romantic poses [dressed in what looks like pirate costumes] in the foyer of a mansion decorated by Harvey Norman called Pebble Court. The ‘Pins are in the company of an preening, loud mouthed character who practically steals the show – and if you’re thinking that’s just a cheap shot at Philip Brophy, you’re wrong, we’re talking about a Sulphur Crested Cockatoo who is seen looking a little surprised at being in a performance piece. At just one minute, the work moved fast and did its thing. It was rockin.

The Kingpins, Take Me To Your Dealer, installation view.

Another DVD piece that rocked in a different way – the kind of rocking that made you feel nauseous, like a boat – was Sydney Infinity, a video of the group dancing around on the roof of a Darlinghurst apartment block with the Sydney skyline in the background at dusk. They’re wearing headbands and t-shirts that ask WHO MADE WHO with fake beer guts hanging out of orange and purple midriff tops and waving ribbons. The viewer has a choice of three soundtracks on a portable CD player– John Farnham’s You’re The Voice, The Choirboys‘ Run To Paradise and Icehouse’s Great Southern Land. The emotional impact of these soundtracks matched to the images was upsetting in the extreme – it was like travelling back in time – first to the Olympics, then to the Bicentennial. The nationalism that was evoked, even in parody, is the Australia that’s killing us – that hideous, backwards and parochial country that decides who comes here and the manner in which they arrive, the Australia that has been co-opted, promoted and sold back to us by corporations and media empires. Who made who? We made us, that’s who.

We like the idea of The Kingpins. We like the idea of a provocative, sexually ambivalent performance art/installation/object making group that takes the piss out of Aussie culture while referencing art history. Looking at the Kingpins’ Kaliman show is a quaintly nostalgic experience for us because in some ways it feels like what the 1980s should have been like [like how if Boy George married Mr. T and they ruled America] but never was. Of course that is the view of old people who like to think that Punk is still relevant and that there are young people out there that understand – it gives old people the idea that their frankly out of date views have some contemporary relevance after all. But then you realise that The Kingpins are products of contemporary art and pop culture and no matter how nostalgic it seems, it is a part of now, not the past. Since they are so much a part of the now, it’d be a mistake to try to pigeon hole them into being exemplars of anything in particular – it’s all still in a process of evolution. And that’s where the no part of the show comes in – The Kingpins are capable of devastating and insightful parody, yet the show felt too diffuse and somehow not the funhouse rollercoaster it should have been. The neon works and the left over props seemed like an afterthought and while we loved the black light pictures, they didn’t sit very well with the rest of the show. What the exhibition should have been was just a single work given the entire focus of the gallery space. It’s the way the Kingpins have been seen in group shows and it’s where they shine.

Over at Mori Gallery, Justene Williams’ show Blue Foto, Green Foto, Red Foto features DVD projections of the artist dressed up in a suit made from her own photographs, dancing around in a mirrored room looking like a disco robot. What’s with all this dressing up that so big in the art world right now? Getting frocked up is undermining the dominant paradigm? Claiming the other for your own spells DEATH to the spectacle? We don’t know, but for William’s it’s all about claiming and escaping your own history. Her recent video work – such as the one at Scott Donovan’s video night – had William’s doing a dance for the camera in a domestic interior. These three video projections done in green, red and blue again feature her striking poses and making moves. Blue Foto has her doing faux-Bauhaus gestures, her limbs constrained by bungee cords; Green Foto looks like a swamp monster and Red Foto has Williams in the abovementioned mirror room [in a strip club, apparently] taking photos of herself. Accompanying the videos is a series of photos of Williams mirror room performance.

Justene Williams, Red Foto As Video, DVD still, 2005.

The show is mammoth and uses the cavernous spaces of Mori’s big gallery well. The video projections dominate the room – rather than the other way around – and although there is a fabulous and undeniable ‘wow’ factor that bowls you over when you walk in, it’s hard not to think of this show as being a very reflective and modest experience. For Williams, the cameras are there to record herself for herself, and the audience is almost there by accident. We are watching a hermetic, intimate experience and the strange theatricality of it just reinforces the deprecating humour. In the smaller gallery, Helen Grace has a video work [mmm, comfy leather couch!] and two series of photo works. Our favourite is the photos called Xmas Dinner Series from 1978, the ghostly silver gelatin vintage prints reminding us of humid Seven Hills Xmas days in the kiddie pool, but the piece Action Without Reaction, a series of shots documenting a performance at the Russian Mongolian border, left us puzzled and confused… What was that all about? It’s interesting to note that the disparity in the sheer size of Williams and Grace’s work, and the gallery space given over to each. Maybe Grace and Williams should get The Kingpins over for a discussion on the long term career prospects for female artists in the Australian art world. Just a thought.

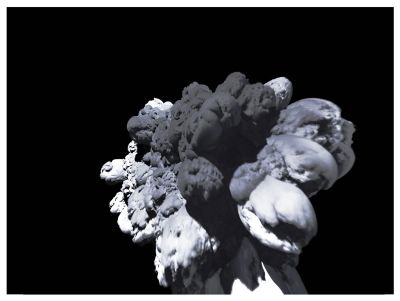

David Haines, Magnetic Anthill Total Affection Unit [Brother Bullnose], 2005.

David Haines has a show at Scott Donovan Gallery called, enigmatically, The Irrational, and it all makes an odd kind of sense. Reading a preview on Haines’s show recently, we were interested to note that he spoke of his SDG show as a chance to do something that connected to the traditions of non-time based art – painting, photography – and that its non-ephemeral nature meant that something would be left after the power was switched off.

What’s emerged from this notion is a series of large scale photographs, pigment prints in a wooden box and three limited edition CDs. The net effect is a cohesive show that’s feels like you’re stepping into some quasi-scientific institution that’s doing psychology experiments on cauliflowers. The wall works are built up from 3D renderings and are suggestive of deep sea or cave rock formations, clouds or even the human brain. The CDs are dark, immersive tones and the titles of the works – May-Jo Fontaine’s Golden Electricity Comb or Magnetic Anthill Total Affection Unit [Brother Bullnose] – suggest that Haines is a member of a pressure group plotting the overthrow of the rational. As an exhibition, The Irrational is a fantastically persuasive experience butf what we’re not sure, but we left believing.

Deej Fabyc, Handle On Nowhere, DVD still, 2005.

There’s something of the irrational in Deej Fabyc’s show at Gallery Barry Keldoulis. But before we get to that we want to ask a question – does anyone read a magazine called Art & Australia? It’s been going for a while now and you may have seen it around. You may have also noticed that we’ve been writing for the magazine for a few issues and the one out now has a column by us where we ask where all the nudity in performance art has gone? We now know that the answer is London, where Fabyc is located and she takes her clothes off for art on an irregular basis. Her installation at GBK is of three door handles called Handle On Nowhere stuck to walls in the gallery and your fist instinct is to give them a tug. There’s no need because they’re trompe l’oleil fakes [and you can’t open nothing, that’s one of the laws of nature] but you really want to. At the end of the gallery, is a video called Handle On Nowhere. Fabyc wanders around a white gallery space naked, grabbing the door handles, there’s a flash from a stills camera, before she moves on to the next one. This carries on until she falls to floor at the end of 5 minutes 49 seconds exhausted. Repeat.

Joanna Callaghan, Empty (detail), 2005.

Bodies, architecture – these things go together – and the nudity seems to underscore both the absurdity of the repeated, meaningless actions and the white space where it all takes place. It’s like being inside the artist’s head. Joanna Callaghan’s work Empty, a series of wall mounted transparencies on a light box that are viewed through slide viewers, is as disturbingly intimate as Fabyc’s work. There’s a narrative of a woman in a council flat somewhere in England. She’s looking over the edge. She looks depressed. Maybe she’ll jump… Then there’s a photo of the artist in the nude [not the woman in the preceding images]. The whole narrative goes bust at this point and the nudity is a defiant, fuck you, “I hold the camera” gesture to you, the male viewer – which kind of works if you’re a woman, except then it’s a gesture of solidarity… we imagine.