As part of our new found determination to seek out other art writing, the sort we actually like, we have the pleasure of presenting a piece for your consideration by Sydney artist, curator and writer Reuben Keehan. Written to accompany a group show at MOP Projects called Eldorado, the exhibition was also staged in Adelaide at Downtown Art Space in March this year. The difficulty of writing an essay to accompany a group show is much the same as writing something for a solo show – does the writer simply try to describe the thematic connections of the works – a rather dull and workmanlike approach – or do they try to examine the theme by heading off into new territory? Keehan’s solution is to do the latter, drawing in his own interests and reference points in the search for something more universal. If you can connect Marx, Debord, Voltaire and John Wayne in one short essay, you must be doing something right…

The Colour of Avocado: Love, Lust and Loss in El Dorado

…but I own to you that when I cast an eye on this globe, or rather on this little ball, I cannot help thinking that God has abandoned it to some malignant being. I except, as always, El Dorado… Martin, the old philosopher, in Voltaire’s Candide, 1759

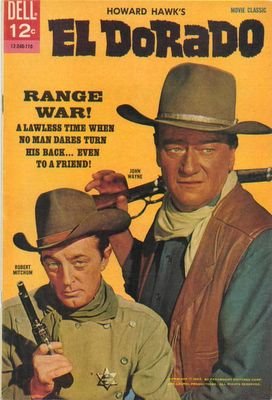

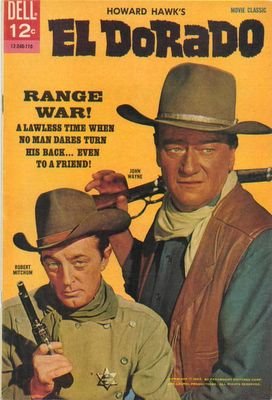

Next time you shoot somebody, don’t go near ’em till you’re sure they’re dead – John Wayne as Cole Thornton in Howard Hawks’ B Dorado, 1966

Christopher Columbus never quite gave up on his desire to discover a westward passage to Asia. When he mistakenly ‘discovered’ the Americas In 1492, he firmly believed that he’d arrived on an island just off the coast of Japan, In May 1502, having been forcibly returned to Spain and tried for his woeful governance of the colony of Hispaniola, Columbus embarked on yet another voyage to the Caribbean – his fourth – with the unwavering conviction that mainland China had to be around there some place, A year and a month later he was stranded In Jamaica, the new administration of nearby Hispaniola understandably reluctant to provide him with any more ships or men in light of his earlier misconduct. Unperturbed, he remained brutally honest With his patron Queen Isabella of Spain on the question of his motivations, These, of course, had nothing to do with proving that the world was round; In any case, most educated people of the time already knew this to be true. No – ‘Gold,’ he wrote in his famous letter from Jamaica, ‘is a wonderful thing! Its owner is master of all he desires, Gold can even enable souls to enter paradise.’

It is the surprisingly eschatology of this particular pearl of expansionist wisdom that Marx caught most acutely in his observation that ‘Modem society, which already in its infancy had pulled Plato by the hair of his head from the bowels of the earth, greets gold as its Holy Grail, as the glittering incarnation of Its Inmost principle of life.’ Discussing the determination of exchange-value as the total accumulation of human labour-time expended in the course of the production of a commodity, Marx noted that it would be unlikely for the price of gold, the universal standard par excellence, to ever accurately reflect the sheer amount of energy that humans have exhausted In search of it. And indeed, Columbus’s letter would set the tone for the wholesale rape of the American continent, a rape undertaken with a fervour that not only bordered on the religious, but which exploited it to the hilt.

Shortly after Columbus had set out his manifesto of avarice-most-pious, tales began to circulate of a mysterious ritual performed by the Chibcha people in what is now Columbia. According to the legend, the Chibcha would cover their chief in gold dust, which would then be washed away in a lake as emeralds were cast into the water in tribute to the earth mother Bachue. Among conquistadors obviously eager to confirm their places in heaven, the story was embellished first to describe a mythical king they called ‘EI Dorado’, the gilded one, and then to encompass an entire country of the same name, where gold was said to be as plentiful as sand.

The influence of this myth was profound, its evolution from tale of simple potlatch to a legend of untold riches indicative of the mania for wealth that continues to characterise modern society. But in its elusiveness, confounding even the efforts of Sir Walter Raleigh as he attempted to regain Queen Elizabeth‘s favour after marrying her maid of honour, El Dorado also came to represent an arcadia untouched by European greed: paradise in and of itself. When for instance Voltaire’s youthful adventurer Candide stumbles into El Dorado, he discovers ‘men and women of surprising beauty’ and fleet-footed ‘red sheep’ – presumably llamas -surpassing ‘the finest coursers of Andalusia, Tetuan and Mequinez.’ He concludes – perhaps glibly – that he has discovered a country that is ‘better than Westphalia’.

Candide is taken to meet with an elderly courtesan – ‘the most communicative person in the kingdom’ – whose explanation of the country reflects much of the shift in ideology of Enlightenment Europe: The Spaniards have had a confused notion of this country, and have called it El Dorado; and an Englishman, whose name was Sir Walter Raleigh, came very near it about a hundred years ago; but being surrounded by inaccessible rocks and precipices, we have hitherto been sheltered from the rapaciousness of European nations, who have an inconceivable passion for the pebbles and dirt of our land, for the sake of which they would murder us to the last man.’ This section of Voltaire’s book ends with a return to the legend’s origin in potlatch, with Candide and his companion Cacambo hoisted over the mountains onto two ‘red sheep’, accompanied by one hundred ‘pack sheep’ bearing provisions, curios, and a range of precious stones.

El Dorado, then, holds a dual role in culture. It is at once a panacea and a territory ripe for exploitation. And though that theme resounds painfully throughout an entire history of conquest and subjugation of which the murder of the Americas was but a bloody, drawn out moment, it is a tension from which the best and worst of Western culture has emerged. As a country always ‘Over the mountains of the moon/In the valley of the shadow’, when this very shadow is that which has fallen over the heart of Edgar Allan Poe‘s gallant knight as he realises that he has found ‘No spot of ground/That looked like Eldorado’, El Dorado also represents the melancholy that inevitably follows from this anxiety. These threads converge in what Debord describes in his Critique de la separation as ‘the sphere of loss’. All this, says Debord, ‘finds in that strangely apt old military term, en enfants perdus’ – lost children – ‘its intersection with the sphere of discovery, of the exploration of unknown terrains, and with all the forms of quest, adventure, with the avant-garde. This is the crossroads where we have found ourselves and lost our way.’

As in a blurry drunken vision,- the memory and language of the film fade out simultaneously. – uncredited film note

Reuben Keehan February 2006