The corpses continued to pile up in the Art Cemetery last week. Erik Jensen’s obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald on Wednesday Angry young artists get the brush-off – farewelled someone you could be forgiven for thinking might have been pushing up daisies for a while now: the Angry Young Man of Australian art. It was a decent send off: a whole half page in the general news section with fancy colour reproductions and accompanying tributes from two Sydney art stars.

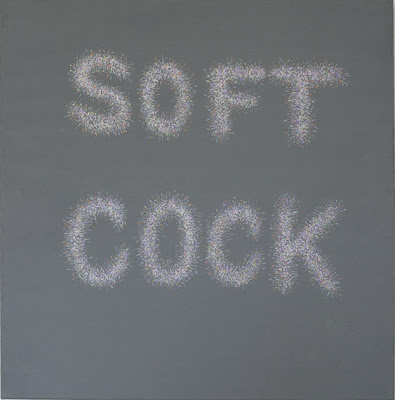

Jake Walker, Soft Cock, 2007.

Acrylic on canvas, 65cmx63cm.

Courtesy of the artist

It’s clear these Bad Boys, Adam Cullen and Ben Quilty, feel the loss keenly. Here’s Cullen on the new generation of art students:

“They’re boring and dumb and weak, very weak. They have no endurance…I met students who weren’t aware, and I just thought what’s the problem? Aren’t you angry, aren’t you in pain? Don’t you know what pain is?”

Quilty is apparently so pissed off he’s picking up his palette and leaving the Chardonnay-sipping Sydney art scene for a potato shed in the country.

Of course, it would be easy to dismiss Cullen’s early-opener ravings by simply pointing up the fact that it is awfully girlie of him, as an artist firmly entrenched both critically and commercially in recent Australian art history, to be whingeing in a middle-class broadsheet about the decline of moral commitment in art from the safety of his mountain retreat. And, pressing the point a little further as an Art Life reader did in a letter to this blog last week:

“Please explain to me what is so “angry” about Quilty’s paintings???carefully considered and technically proficient paintings of skulls and cars??”

Point taken.

Another approach might be to dispatch the whole sordid affair with the bloodless precision of Joanna Mendelssohn in her published letter in the Herald on Friday:

“That angry old artist Adam Cullen should use his eyes…Most art students were women in the 1890s, most were women when Cullen was a student. And most art students are still women.There are other constants. Ageing radicals whose macho fantasies with dead animals hang in designer collections still complain about the young.”

Ouch.

But that would just be shooting fish in a barrel (and everyone knows guns are for cowards). More importantly, it might mean missing an opportunity to generate a meaningful conversation about some of the key issues that significant artists like Cullen and Quilty who, by having their say, manage (sometimes in spite of themselves) to raise in the popular narrative about what art is, what it should be and do, and what the place of the artist is in all this.

Jensen’s article is a veritable dictionary of received ideas about art. It maps shifting trends in the art market – away from rude, crude, hard and fast picture-making towards refined, considered, quieter work – along gender lines. It relies on embarrassingly romantic ideas about labour in relation to style and substance. It assumes an awful lot about the political role and the ethical commitment of the artist. And it is largely blind to the specific history in which such ideas became received wisdom in the first place.

None of this is the journalist’s fault. It’s pointless to get too uppity about how mainstream media continues to be reductive in relation to art culture. For one thing, younger generations see the SMH as a self-evident, cultural irrelevancy. And Jensen’s article does raise some important practical concerns that plug directly in to the broader ideological framework in which more nuanced art discourse takes place. For example, as Quilty rightly points out, there are real socio-political problems associated with the recent closure of the UWS art school that need to addressed.

Judging from the visceral reaction to Jensen’s piece (my own included) it seems lots of us actually care about this stuff. (According to Cullen, the phrase ‘white, macho, Nazi pig’ was bandied about a fair bit.) And what a good thing that is. I think it’s heartwarming.

From Carrie Miller.