Regular Art Life reader Ian Houston is now our semi-official New York correspondent. For a follow up to his previous postings, Mr. Houston writes to us on the exhibition High Times Hard Times New York Painting 1967 –1975 at National Academy of Art NYC, curated by Katy Siegel.

Where did it all go wrong? There was a time when canvas painting was the highest expression of contemporary art. We knew this because Clement Greenberg told us so. But nothing lasts forever. The history of Greenberg’s theory of formalism and the extraordinary hold it took on world art is well known. What is not so widely discussed is what happened to painting in the aftermath of Greenberg’s fall from grace, as it faced the challenges of minimalism, conceptualism and the rise of sculpture as the critically acknowledged “pre-eminent” art form. Which is a shame, because as we all know, most parties are much more interesting once the last wine cask bladders have been emptied and people start eyeing the cooking sherry. Desperation takes hold and people try things they would never have dreamed of at the start of the evening. That’s the way it was at the end of the sixties, as painters, freed from the straightjacket of Greenbergian formalism and in response to the political foments of Vietnam, Kent state and the Summer of Love™, tried to make painting matter again. Sure they failed, but what a glorious failure it was. High Times Hard Times is an exhibition devoted to examining this explosion of method, technique and theory as painters and painting tried to make sense of a “new world order” that seemed to have left it behind.

Alan Shields, Whirling Dervish, 1968-70.

Acrylic and thread on canvas over wood, 38×107″ d.

The National Academy of Art on Park Ave is the loneliest place on museum mile. No surprise really, given that its across the road from the Met, next door to the Guggenheim and a block away from about half a dozen other galleries, all showing blockbuster artists with mega million dollar paintings whilst its rooms are filled with a bunch of paint stained rags by some drug addled hippies. Which is why the staff here are probably all so surprised to see me. Once they have ascertained that I am actually here to look at a lot of very obscure abstract art from the seventies, they practically fall over themselves to make my trip as comfortable as possible, stuffing my hands with brochures, discount cards and maps whilst privately shaking their heads at the foolishness of my passion.

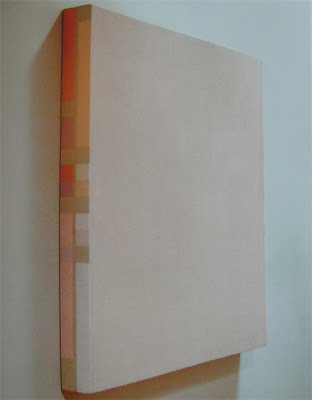

Cesar Paternost, El Sur, 1969.

Acrylic on canvas, 48in x 48in x 4 3/4″.

Sadly, despite the help offered by the staff, the venue itself is wildly inappropriate for these kind of works, with the curves of its neo baroque walls leaving larger canvases jutting uncomfortably from the surface and the rooms being too small to give some of the more expansive works the kind of space they’re insane aesthetics require. But that’s alright I tell myself, because many of these pieces would have been completely forgotten, stuffed in the archive warehouses of public and private collections across the land, were it not for this show.

The exhibition is arranged in a rough chronology grouped around responses to general themes, be that political interventions, abstract formalism or the impact of video as a new medium, though the sheer randomness of some of the work makes them close to unclassifiable. But this is the least we should expect from the “Brown acid” generation. After all this crazy group of kids were working in the shadow of one of the great flowerings of American culture, from the development of Be Bop, free jazz, the poetry of the beats right through to the New York school of abstraction, New York had become the cultural capital of the world. Yet this legacy had been secured through a series of shattering academic shifts that, at the same time as ensuring the avant garde’s legitimacy, would have to be paid for with a kind of theoretical end game that would eventually herald the nihilism of Post Modernism. So it is easy to view this collection, with the benefit of hindsight as a kind of last gasp art of desperation by people who had become marginalised by theories ascent to instigation rather than investigation.

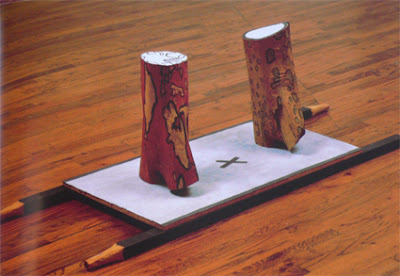

Ree Morton, Untitled (stretcher piece), 1971-73.

Mixed media 21in x 21 1/2 in x 66in.

The first room starts gently enough. Here we see the initial stirring of dissent at the strictures of Greenbergian formalism. Unsurprisingly, given the literalness of the theory they seek to usurp, they are a very literal form of rebellion. Cesar Paternosto refused to paint on the front surface of the canvas instead decorating the edges of the stretcher frame with hard edge compositions. As juvenile as it at first seems, this refusal to dignify Greenberg’s ideal of the flat picture plane leads to works such as El Sur whose oblique beauty is found as you negotiate its “four sides” (though I would have needed a step ladder to see the upper side). This attack on the ideal of “flatness” was continued vigorously through a variety of modes. There are tent like canvases erected on the floor such as Alan Shield’s Whirling Dervish, or his Put a Name on it Please which consists of string, cotton belting and beads tied in fragile netting that maps the space of a canvas painting. Then there are paintings that refute the ideal notion of the canvas space by using stretchers that are made of things such as rough untreated pine logs – #13 by Peter Young or are literally hospital stretchers, Ree Morton’s Untitled (stretcher piece) 1971. Other canvases feature punctures, cuts, bare stretchers or paint and medium applied directly to the wall or floor. Indeed every possible means of refuting Greenberg’s idea of purity seems to have been taken. Which must have made Clement feel kind of angry.

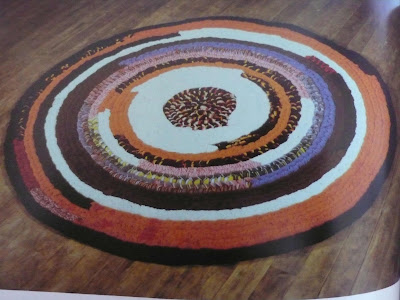

Harmony Hammond, Floorpiece V, 1973.

Fabric and Acrylic 59″ d.

Feminism, naturally enough, was one of the primary motivational forces in this reappraisal of painting. Greenberg and the New York school painters were rightfully considered a bunch of prigs from the patriarchy, so the sisters would take any chance of upsetting the apple cart they could. To begin with many of these efforts were concerned with “flatness” and the Greenbergian ideal. But they soon took in a whole host of other concerns, including notions of gendered craft, the feminine body, the phallus and the materiality of the work. Harmony Hammond’s work was created from rags blankets and hand me downs. This included “Paintings” that were made from twisted rags woven into circular mats and then left to lie on the floor in a manner that looked very like a rug. Mary Heilman also used rags sewn together to make a “book” which she then spray painted black, The Book of the Night 1970, a particularly beautiful piece. Dorothea Rockburne, sought to make work that was intensely sensual and emotive as a revolt against the perceived intellectual rigour of Abstract Expressionism’s Platonic ideals. Her Intersection 1971, is a standout, crude oil is sandwiched between two very large sheets of plastic and left to lie on the floor. The smell of the crude fills the room whilst the oil lies inscrutable and black, bubbling with rainbow sheens at the edges of the work.

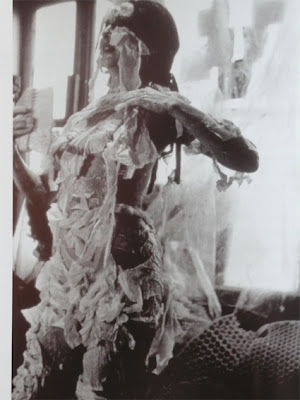

Carol Schneeman performing Body Collage in her loft on west 29th st NYC.

Film was also used as a means of inspiring and recontextualising painting’s practise. Painting performances were filmed in which tribalism, ritualistic behaviour, Dionysian frenzy and wah wah guitar were all encouraged in the kind of psychedelic frenzy that has kept “the summer of love” alive in the minds of teenage boys everywhere. Carol Schneeman’s Body Collage is emblematic of the period’s values. Schneemann paints her body with wall paper paste and molasses, runs, leaps, falls into and rolls through shreds of white printer’s paper to create a scary hippy monster, which she relates to the moving image of a flayed body as standing for the devastation of Vietnam. Interestingly, she remained intent on holding onto these pieces of filmed art as “paintings”. She refers to this work as “as an exploded canvas, units of rapidly changing clusters.” Similarly Yayoi Kusama’s 1967 film Self Obliteration made with Jud Yalkut is a collection of scenes from indoor “happenings” cut through with footage filmed in New York’s central park, the whole being brought together with Kusama’s signature use of dots, which cover people and objects. The film features the orgiastic sexuality of the hippie peace and love culture in a performance of “painting” in which the bodies gestures and movement is linked to the notion of the abstract painting.

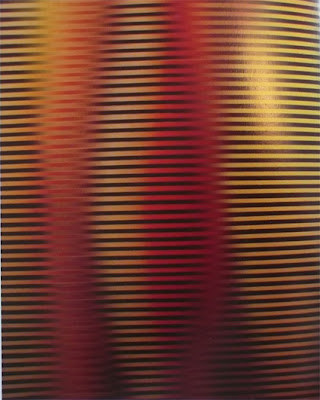

Roy Colmer, no 102, 1973.

Acrylic on canvas 75×60 inches.

The impact of video was huge. Not only in terms of its possibilities as a new medium but in terms of the aesthetic its grainy pixelated screen could reveal. A number of painters experimented with recreating these colours and tones with a painting that used “interference fields”, spray painted tonal works that replicate the texture of the video screen and its strangely luminous hypnotic appeal. Roy Colmer’s work explored the abstract qualities of video feedback both in video installation and on the canvas with a series of spray painted works that sought to replicate the “flow” of this phenomenon. Michael Venezia painted enormous canvases with Aluminum pigments and black enamel that resemble television static. Lawrence Stafford used spray guns to paint horizontal stripes across the canvas that would “interfere” with each other as they spread across the surface, creating bands of “static”.

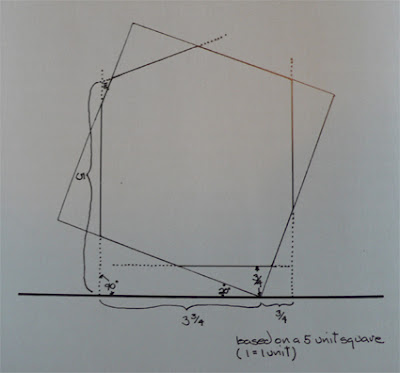

Richard Tuttle, Diagram of 11th paper octagonal, 1973.

Perhaps my favourite work in the exhibition, if such a hegemonic perspective can be allowed, is Richard Tuttle’s 11th Paper Octagonal 1973, a piece of paper that has been cut out according to the instructions he had sent to the gallery and then stuck to the wall in a place that the curators found pleasing. There it was, a piece of white bond paper in a pleasing octagonal form, sitting peacefully on the wall, unaware of the ferment of ideas and politics that had elevated it to that place. It seemed to me to truly be an ineffable signifier, a white on white hole that led to a space of sublime implausibility. A rabbit hole to 1968, a world where ideas mattered in ways that we can no longer understand, though we wear their clothes, play their guitars and smoke their drugs.

It is peculiar to think of how this sentimentality for the idea of the painting, and the desire of these artists to hang onto it co-existed with a tremendous surge of rebellion in which the same artists would do whatever they could to contest the idea of it. It was as if, through the simple idea of making the term “Painting” all encompassing, they could ensure its legitimacy as a practise. This contested site could then become the metaphorical extension of their “thinking through” of the world. The work itself mattered less than its expansion into the theoretical domain and from there, into what could almost, be understood as a “praxis”. A place where their actions mattered because they had politicised the theoretical underpinnings of their practise. This perhaps is the great irony of Greenberg’s work, by invoking teleology he actually wakes Hegel from his slumber and gives birth to a whole generation of artists, who in a frenzy of antithetical gesture contradict Greenberg’s conclusions, yet make the dialecticism of his premise seem sound. If only I had of been there, with some flowers in my hair. Peace man.