After 156 years of British rule Hong Kong reverted back to Chinese rule in 1997. It’s now officially known as Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). From an international centre of trade and commerce with a population largely uninterested in politics, the new Hong Kong with its three very different cultures – traditional Chinese, communist Chinese and British capitalism/democracy – is becoming increasingly political. The younger generation, most of whom are well educated and articulate, are starting to speak out at what they see as the suppression of the many rights they once enjoyed.

The work of artist Tsang Kin- Wah reflects some of these social and political realities and is seen by many as one of the ‘new’ Hong Kong’s most interesting voices.

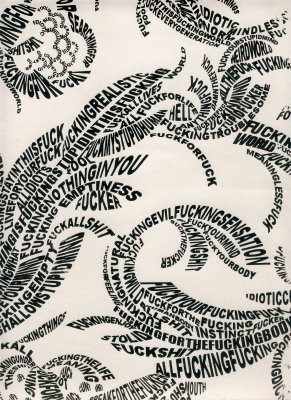

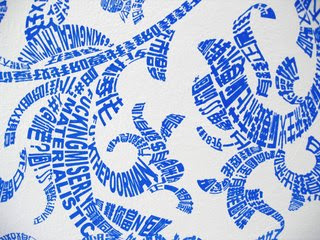

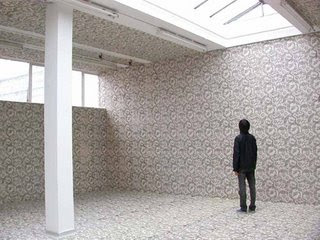

Tsang Kin Wah was born in 1976 in Guangdong China and migrated to Hong Kong in 1984. He travelled and studied at London’s Camberwell College of Arts, before returning to Hong Kong. His work is at the most direct level a play between the difference between appearance and reality, and can be described as quaint and acidic. Wah’s Wall paper series (Untitled works 2003/2004, Interior 2003) are hand printed wall papers in the traditional pattern design of William Morris and when installed covers every inch of the gallery space. On its surface the work appears very “British “, very elegant, very controlled and very tranquil. Tsang received the Prize of Excellence in the 2001 Hong Kong Biennale as well as various prizes in painting, watercolour and drawing – which shows through in the obvious attention to craftsmanship in the Wall Paper installations – a surface of beauty and elegance that masks a deep anger, dissatisfaction and frustration that only becomes apparent on closer examination.

Wall Paper uses text as a visual image not unlike the work of another Chinese artist Xu Bing. Wah acknowledges that both calligraphy- which in Chinese culture is considered one of the highest art forms, and Xu Bing, has been an influence. Where Bing makes it a point that his calligraphy is unreadable and where the Chinese ‘calligraphy’ is in fact not Chinese characters at all but something invented by artist – Wah’s work is are elegant surfaces that need to be read as text for the whole work to emerge.

When you move closer and read the text, you realise that the words making up the patterns of plants and flowers are texts that simmer with resentment and anger: fuck, fuckers, fuckingwealthycunts, Fuckingmaterialists, fuckthepoorman.

We asked Wah about this duality in his work. Was this play on a beautiful surface that hides an ugly reality the essence of his work? “This is one of the main ideas, or you can say that is the most powerful thing in my works that switch the viewer’s point of view from one to another extreme. For me, this is one of the things that we experience a lot but forgot sometimes. Nice appearance equals nice interior? I don’t think so. To some extent, my work is also a reflection of myself which seems pretty shy and quiet but has much anger towards different things that happen around me.”

In an interview about his work for Shanghai Magazine Wah explained, “[The work is] a space of criticism, of contradiction, of nastiness. What the viewer see is selectively presented by the creator, it indicates that some information is either consciously or unconsciously being left out by the creator. To doubt, to explore, to challenge the traditional perspectives that exist can create a new dimension, to enable you to investigate what’s considered as ‘normal’ or ‘obvious’ around you in a critical manner. You can then create a new perspective to inspect everything.”

Wah’s anger perhaps stems from his background. In general, based on current political events, it is safe to say that the people of Hong Kong are angry. It’s the kind of anger that runs deep, the kind of anger that may not be noticeable on the surface but it is definitely simmering away. Speaking about his work Wah commented, “This contradictory space is like human condition. To live in the society, we have to suppress our emotions be it happiness or sadness. There is just no way out to express it. When you see the foul language in these wallpapers, you will suddenly realise those are the messages you want to scream out aloud, messages left behind or hidden in your heart.”

Before the handover Hong Kong and its people weren’t much interested in politics. What mattered was commerce, the market, profit, having a good life style. Hong Kong was the essence and a symbol of a free market economy. Making money and staying away from politics was almost a lifestyle. Very few people wanted to disrupt the system that was giving them access to every kind of material goods one could imagine and a lifestyle comparable to, and perhaps even better, than many of those found in western countries.

After 1997, the arrangement “one country, two systems” meant that China could restrict the rule of law and many basic democratic rights. On the 1st July 2003, the Chinese/Hong Kong Government decided to control freedom of public speech and proposed to amend the basic law known as Article No. 23 which meant censorship of the kind Hong Kong people hadn’t experienced. In response, a new class of well educated, young professionals with western democratic ideals began to form a popular democratic movement all over the Territory. People began missing the things they’d taken for granted – freedom of speech, freedom of free assembly and free expression – be it economic, political or artistic.

Wah’s work is a reflection of this political reality and is thus intended to be read on several layers – the floral image for example is highly indicative of sex and sexual organs – again another cultural taboo in the new Hong Kong. By using floral imagery Wah manages to address this taboo and yet be “acceptable”.

We asked Wah whether the play between appearance and reality in his work was a way of subverting certain types of cultural taboos, or even censorship of presenting a somewhat harmless looking work on the surface but one that is actually quite subversive? “The socio-political situation in Hong Kong did affect me quite a lot in the past and still at this moment. I would watch the news report everyday and look at the people or things that happened around me. Many queer or weird things gave me much inspiration for my work. Hong Kong is not subversive and that’s why I want to challenge it… or may be because I really hate it.”

The younger generation have unique problems created by an education system operating under the notion of “one country with two systems”. Currently schools teach in two languages and two sets of values. Young people in Hong Kong also have to deal with values, propaganda/ information from a media controlled by the communist Chinese and the values of their parents and grand-parents from a more democratic past.

Hong Kong doesn’t totally belong to the British or the Chinese – it’s a mixture of both cultures. Passports are stamped with the phrase British National Overseas – but without any of the rights or privileges that come with being a recognised citizen of the United Kingdom – an illusion – an appearance of belonging to something that really does not match reality. For years the joke of ‘having no identity was a unique identity’, was the common response by many Hong Kong citizens dealing with a schizophrenic identity.

Wah’s artistic career is in fact is a bit like watching Hong Kong – he belongs to the long history and culture of China but then again maybe not. He lived for some time with British culture and can function well in it, reference it, play with it as one would with something that is not only familiar but that you have internalized as your own- and yet it is not your own – the invitation to stay has expired….

At the end of our interview we went back to an earlier phrase that struck us. Wah had said, “When you see the foul languages in these wallpapers, you will suddenly realise those are the messages you want to scream out aloud, messages which are left behind or hidden in your heart.”

This to us spoke of repression, yet it seemed that Wah was still a successful artist. His work has been shown in some prestigious exhibitions and he’s received numerous prizes, accolades, scholarship and residencies. It seems that instead of being repressed or censored, Wah’s work is actually accepted, shown and praised. Wah was not unaware of the irony. “Yes, my work has been shown in some ‘prestigious’ exhibitions and it seems that my work has been accepted but I don’t think that they really understand or accept my works,” he explained. “I remember some cultural administrator once told me that they like the images of my works but not the text…”

Between appearance and reality, Tsang Kin-Wah highlights the importance of engaging with the world not as it seems but as it actually is. The point of course is to figure out the difference. We have the artists intentions to go by – that it’s an institutional critique. We have the institution supporting the very criticism intended for it – effectively swallowing up the work and nullifying the artist’s position along the way. It’s hard to know where to stand – an objective impossibility in the face of mismatched reality, leaving wide spread cognitive dissonance and a schizoid world-view in its wake.

The idealist part of our brains says that an artist’s intention counts – and that his success is in some ways is also his failure. Art is made from a certain innocent belief that it can provide an alternative and unmask political sleights of hand (that gives as as it takes away) The more realist part of our brains meanwhile says that institutions subsume everything thrown their way – and that it’s better to be heard than not, and that playing for real means knowing after all the rules of the game – and beating it. While the cynical and jaded parts of our head howls out that if art and life is hide and seek game called appearance versus reality – then institutional criticism is after all just one position amongst many, and that there is such a thing as rebellious conformism.

Maybe its one of these or all of these things…

The joker in the pack on the other hand thinks that what matters in the end (in art as in life) is perhaps neither appearance nor reality – but that works for whatever they are worth will be made, despite or in spite of it all – and sanest are those who can do so in laughter.

From The Art Life’s HKSAR Special Correspondents