It would be hard to think of another artist who has had the same sort of impact on the visual culture of Australia as Reg Mombassa. As one of the key artists working for the Mambo street and surfwear empire his designs defined a period that began in the late 1980s at the birth of the label and stretched all the way through to the Sydney Olympics closing ceremony in 2000. From his first t-shirt designs through to those gargantuan puppets shambling around the Homebush stadium, Mombassa’s livid fantasies were both mockingly ironic yet sincerely honest depictions of Australian life. And they were hugely popular too. It seemed that every suburban Dad in the country had a Mambo Hawaiian shirt, worn proudly while taking the kids to weekend soccer or washing the Holden in the drive. Mombassa’s graphic work defined an attitude, a time and a place – and that’s before we consider his other job as a guitarist and songwriter with Mental As Anything, one of the finest pop bands to emerge in Australia in the late 1970s.

Born Christopher O’Doherty in Auckland, New Zealand in 1951, Mombassa displayed an enthusiasm for both art and music from a young age, studiously copying old masters in his bedroom art studio, while listening to records or practicing his guitar. Following his parents to Sydney’s Northern Beaches after finishing high school in New Zealand in 1969, Mombassa held a series of depressing dead-end jobs before heading to art school in the mid-1970s. At East Sydney Technical College he fell in with a bunch of arty bohemians in love with jokey, Dada-inspired conceptualism. Mombassa also met future collaborators Martin Murphy [aka Martin Plaza] and Andrew “Greedy” Smith. Here the split personality that is Mombassa/O’Doherty began to emerge – one a blues-inspired guitar player, the other a mild-mannered exhibiting artist.

Murray Waldren’s biography of Mombassa, The Mind and the Times, promises to reveal the “mind and times” of the man but really only achieves half its aim. Drawing on extensive interviews with family, friends, band members and many others – not to mention a mountain of quotes clipped from music magazines, newspapers and websites – Waldren has written a trainspotters view of history. Nothing seems to have been left out. We get a detailed account of Mombassa learning to drive, an anecdote about the first car he bought in 1971 – a Rover 105R, the head gasket eventually blew up – two pages on whether the first Mentals gig was on August 16th or August 17th, 1977. There are lengthy digressions into family history, pen portraits of enthusiastic fans, a page or two on how Greedy Smith busted his elbow falling off a horse in 1989. There are long accounts of the making of all the Mentals albums and their endless touring. But even at 400 pages Mombassa remains as an elusive a figure at its conclusion as he is at the start.

Waldren’s book never properly tackles the split between the two sides of Mombassa’s artistic personality. There’s plenty of detail but little in the way of insight. Waldren quotes some academics on Mambo’s eclectic style but they are the only voices in the book with a critical distance on their subject. It may be that the author is just too much of a fan to take a step back and seriously assess Mombassa and his art. For lovers of Mombassa’s exquisite small-scale landscape paintings or for those who want to luxuriate in a huge archive of photos of the Mentals, The Mind and the Times is a handsomely illustrated tome. The problem lies more in Waldren’s flat journalistic prose. His occasional forays into more descriptive passages are a headache-inducing melange of mixed metaphors. While discussing Mombassa’s explorative inspirations for his Mambo designs, the author writes, “It was in the less controlled exploring that [Mombassa’s] distinctive vision flowered. At times this seemed to involve hurling himself into a stream of unconsciousness, from which he would find himself washed up on strange shores indeed, sometimes in a fantasy land, sometimes in sexually enigmatic posturing.” This might be a joke, then again, perhaps not.

Late in The Mind and Times it’s mentioned that Mombassa keeps a diary. Small excerpts are scattered through the book suggesting a far more enjoyable and idiosyncratic autobiography is yet to be written, perhaps one that that might sit on the shelves next to other great rock memoirs like Julian Cope’s Head On or Alex James’s Bit of A Blur. There is certainly plenty to cover. In his forward Mombassa admits that the thought of a biography wasn’t all that appealing but commends Waldren on ordering this “impenetrable tangle of facts” into a readable whole. On that I’d have to disagree. It’s revealed early on that Mombassa never liked surfing – “too wet” he says. There’s probably something in that worth exploring.

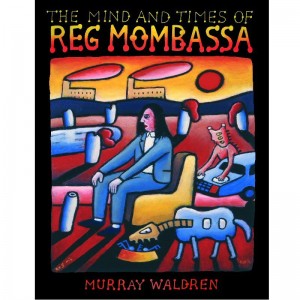

The Mind and Times of Reg Mombassa

By Murray Waldren

HarperCollins, $75

This review appeared in a slightly different version in Spectrum.