Early on in the documentary Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress and the Tangerine the artist makes a startling observation. No artists should receive any kind of financial support from governments because, says Bourgeois, “being an artist is a privilege because they are in contact with their subconscious.” Ever the willful outsider, Bourgeois mined her own life, psychology and imagination for her raw material letting no man, organisation or her own formidable reputation get in the way of her artistic desires.

Directed by Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress and the Tangerine [2008] has the advantage of the long view. Shot over a decade from the mid-1990s until the latter 2000s Bourgeois emerges as an irascible grand dame, exacting in her personal affairs and prodigious in her art making. As the directors ask straight-forward questions, Bourgeois rails against the stupidity and ignorance she believes lurks behind the seemingly innocent inquiries. In life, as she was as an artist, Bourgeois looked beyond the apparent surface of things for metaphorical meanings, and her answers to the interviewer’s question are an almost stream of consciousness ramble yet compelling in her exacting creative methodology.

The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine is structured around three key aspects of the artist’s life. The spider was one of the artist’s main recurring motifs, a creature of no definitive meaning in the symbology of her work [although referred to by the artist as ‘mother’] and which, through its eight legs, created a series of ‘relationships’ between its body and the outside world. Bourgeois’ spiders are her best known works, and with some canny business insight, her editioned sculptures are now planted around the world. Bourgeois’ problematic relationship with her father – and the estrangement and betrayal she felt when her live-in nanny became her father’s live-in mistress – formed another crucial and openly acknowledged part of her artistic biography, as was the tangerine, both in its form and colour, and again in its significance as part of her personal story.

Bourgeois was not a joiner. Living in New York during the Second World War she rebuffed the social circle around the Surrealists in Exile group – Andre Breton, Andrew Masson et al – and although Bourgeois’ work was in essence an almost pure expression of the Surrealist impulse she had no time for the pasty theorists and artists – “I hated their lordly ways,” she says dismissively. Being venerated as a role model to younger women artists in New York – and the Guerrilla Girls in particular – was viewed by the artist at a skeptical but respectful distance.

As is often the case with contemporary art documentaries, The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine places a huge emphasis on its production style – gliding cameras, suggestive music, interviews with the artist, family and art world acquaintances, smartly edited archival material. Despite its formulaic structure, The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine succeeds because its directors create a portrait of the artist as a real human being. They leave in all the difficult material – the artist berating the director, having tantrums and walking off the set, frank admissions from family and friends that Bourgeois was far from ‘nice’ [curator Robert Storr, who worked with the artist and knew her for many years, comments that he managed to remain friends despite the fact that “everyone gets wounded by Louise if they stick around”]. But more than just a ‘warts and all’ portrait, the viewer is left with a real insight into the artist, her work and her life.

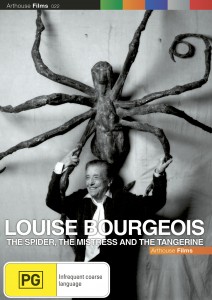

Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress and the Tangerine

Dir: Marion Cajori & Amei Wallach

Runtime: 89 mins

Arthouse Films/Madman