Din Heagney‘s latest postcard arrived in the mail. He’s in Berlin, in a melancholy mood…

Dear Art Life,

I had the chance to pop into Berlin to visit some Aussie mates living there, the artist/design duo Pandarosa and the novelist Lollie Barr. Once we worked off the hangovers, we decided to visit the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum für Gegenwart (Museum for Contemporary Art), a converted railway station that is now home to the rather enviable collection of modern art owned by the Flick family. I’ll do my best to avoid a joke about Herr Flick, the Gestapo officer from ‘Allo ‘Allo, but actually the reference isn’t too far off. Having bumped into a local choreographer who gave us a quick history lesson in the museum, I was more than a little disturbed to discover the story behind the Flick Family collection on show, featuring key pieces from the likes of Warhol and Beuys.

Freidrich Flick was the founder of one of the industrial giants from Wiemar Germany, and later became a founding member of the Nazi Party. The Flick empire expanded throughout World War II, becoming the largest producer of arms for Hitler, profiteering from Jewish property stolen by the Nazis and, most disturbingly, turning over vast sums of money in his factories by using concentration camp prisoners as slave labour. Most of these prisoners died in the labour camps. Flick was later convicted of war crimes at the Nuremberg Trials in 1947, and although being given a lenient sentence of seven years, he served less than half. Following his release, he went on to rebuild his empire and his enormous art collection. By the time he died in the early 1970s, Flick was one of the wealthiest men in the world.

Years later, his son and inheritor of the family fortune, Friedrich Karl Flick, offered to present his art collection in Switzerland but the Zurich authorities blocked the plan, citing Flick’s refusal to compensate war victims as a major reason. In 2004, the Hamburger Bahnhof would take up the offer to show the priceless but controversial collection. There were protests, but the museum placed the value of the collection and its public presentation over its dark acquisition history. It reminds me of seeing the so-called Elgin Marbles in The British Museum, torn from the rocks of Greece, presented in some remnant context of imperial posterity. Then again, there is the flip side of this issue of repatriation, such as The Natural History Museum in London just announcing the return of 138 sets of skeletal remains of Indigenous Australians to the Torres Strait Islands.

So here I am, surrounded by these wonderful works of modern art, but now I’m in a dark mind, they are polluted in some fundamental way. History, or perhaps more properly put, remembrance, is a powerful energy. I find it hard to separate the past from the present. The more you know about the past, the more invested you are in the present, and the more you are simultaneously torn but energised by the potential future.

A wonderful art collection built on the suffering of others is not a wonderful art collection at all; it is dirty, and I think everyone suffers in the end. Those who have suffered to provide the means, those who have profited from the means and those bastards who are just plain mean. Is it a stretch to say that this is an indicator of some of the darker forces that play out in the financial aspects of the art investment market? An artist cannot usually choose where their works will end up, but it seems to me these pieces are also a little like prisoners themselves; still serving a greater master and awaiting their own freedom.

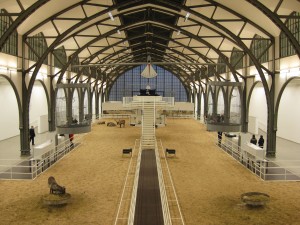

Despite this inescapable heaviness from the past, embodied by the Flick collection, I was still excited to make it to the museum to see Carsten Höller’s incredible SOMA installation. This massive and complex commission had already captured the imaginations of more than half a million visitors, making it one of the museum’s most successful blockbusters to date. If we flick Flick aside for a moment, we can consider Höller’s work in its own right.

For me, SOMA was an inspired treat from inner space. Part psychedelic science experiment, part sideshow spectacular, SOMA was a powerfully realized exploration of the science of getting high. More interestingly, it revealed some of the difficult relations between scientist and specimen, artist and audience, human and animal, direct and indirect experience.

To describe the construction and interaction of SOMA in detail would take too many words. But to give you a picture: imagine a cross between a live exhibit at the zoo and a science lab of reindeer, now add some giant segmented mushroom sculptures, rows of enormous cages filled with canaries, blowflies in experimental videos, fridges full of urine samples and finally a space age, elevator bed hanging over the whole thing. There were many different entry points to the work, both physically and figuratively.

Most of the exhibition hall was dedicated to an enormous, fenced off reindeer enclosure. The main display was split in two; each side a mirror of the other, a double blind trial, with the enclosures holding twelve castrated male reindeer (and the occasional museum assistant working on a pooper-scooper). The basic premise of SOMA was to explore the efficacy of the hallucinogenic fly agaric mushroom, those red ones with the white spots, which for many years have been considered by some scientists as the source of the mystical soma, the ‘drink of the gods’.

Maybe not coincidentally, ‘soma’ is also a marketed brand of muscle relaxant, one that blocks sensations of pain between the nerves and the brain. This isn’t the legendary drug though; the soma of antiquity has effects that induce trance-like states, creating mystical experiences, hallucinogenic fugues that open up sensory experience to other parts of the mind, some might say the soul.

Research shows that these experiences are not isolated but are common to human history and evolution the world over. The good old mind-bending-chemical is just that: it’s good and it’s old. So the plants and animals of our world have shaped us as much as we have used them in ceremonies and medicine. In effect, we changed our destiny when we drank from the soma cup. Language, music, and art opened us up to deeper experiences, as a release from the everyday and in the search for knowledge.

Whatever your personal opinion of psychoactive drugs, there remains substantial botanical and anthropological evidence that humans have used them for at least 10,000 years, and in many different cultures. Höller’s work largely refers to the Soma Mandala in the Rigveda, one of the sacred Hindu texts, which features 114 hymns sung to the entheogenic (‘knowing god’) qualities of soma, the ‘bringer of light’.

But what’s with all the stoned reindeer and canaries? According to one theory, reindeer can eat the fly agaric mushroom, digest the poisonous chemicals, and then excrete what is considered soma, the golden drink of the gods or, in this case, the golden whiz of Rudolph the red-eyed reindeer.

Watching the interactions between each of the animal experiments was the standard way to view the SOMA exhibit, but for a mere 1000 Euros, you could go the whole way. That space age bed I mentioned was up for nightly hire, and cashed-up visitors, in need of some tripped out reindeer urine, could stay overnight in the museum and partake in the mystical soma experience. I would love to see the video surveillance footage from those overnight stays. I wondered whether people would hold their noses when they drank it or just follow it up with a quick vodka chaser. Then I suddenly remembered that scary Ingmar Bergman film, The Serpent’s Egg, where David Carradine and Liv Ullmann are subjected to horrific drug experiments while secretly being filmed in 1920s Berlin.

Ultimately I felt sorry for the caged animals featured in this science circus spectacular, so removed from their natural habitat that they become curiosities for us all to gawp at. I couldn’t work out what would be more humiliating for a proud and elegant animal like the reindeer: having your blokey bits chopped off, or then having to be stared at by thousands of people every day while you’re high as a kite on a special diet of straw and magic mushrooms. Lollie cheered me up by suggesting that we try to work out which of the reindeer were stoned. She thought it was the ones of the right having a stare-off with each other, but I’m pretty sure it was the big ones lying down on the left side that kept snuffling the air and smelling their feet.

It seems we must dissect life in order to understand that we did not make it; we did not create the reindeer, or the song of the canaries; this was the work of a greater force. It reminds me of a story David Lynch tells; when he dissected a chicken into its various parts, and his young son asked how they put it back together into a living chicken. Perhaps the only way we humans really know something is to destroy it. We know the earth would continue quite happily without us living here and squandering its treasures, but we continue to search for our greater connection to the outer, through exploring the inner. It’s the same search for truth and meaning that our ancestors sought, whether through art or ritual or just drinking pee from a bunch of tripped out, foot-sniffing reindeer.

Expansive as SOMA was, it kept shifting in my mind; one moment being complex but overly sterile, the next minute monumental and more than a little bit surreal. This got me thinking: was Holler’s work an empirical exploration of the dynamics of mysticism? Was it all an elaborate joke on our gullibility for objectification in modern culture? Was it truly an experiment in the potential for enlightenment? Many people in history have succumbed to all sorts of nonsense and terror in the promise of sacred illumination. This is nothing new. I do, however, believe these paths to greater knowledge, that of science and that of spirituality, to both be worthy of consideration.

The fascination we have with this near-mythical drug lies in the possibility of experiencing something more. The stories of soma are as tempting, and probably as exaggerated, as the stuff of legends. Luckily, work like Höller’s SOMA is a genuine connection between empiricism and belief. It’s the kind of art that provides a space for the acquisition of knowledge rather than the acquisition of possessions. It was almost enough to make me forget about all that dirty art in the rest of the museum. Almost.

Din x

IMAGES: Carsten Höller, SOMA, 2011, Hamburger Bahnof Museum für Gegenwart Berlin, installation views. Photos: Din Heagney