Luise Guest reports on two recent shows in New York where masculinity and femininity play out in unlikely forms..

Art in Manhattan: always an exciting mixture of the wonderful, the extraordinary, and the merely deeply weird. This month is no exception. Two exhibitions in particular raise interesting questions about the roles played by artists in a changing world, and about the ways that the physical body has been represented in the practice of artists since the 60s. A major retrospective of the wonderful Lin Tianmiao at the Asia Society Museum reveals an artist exploring the physicality of the body with a visual vocabulary of materials such as felt, thread, silk and hair. A show at the Metropolitan Museum, an unusual foray into the contemporary world for the Met, focuses on a number of significant ideas which include the body in all its various contemporary manifestations. Other shows around town seem to reinforce these notions of the importance of the body in a variety of ways, some more controversial than others.

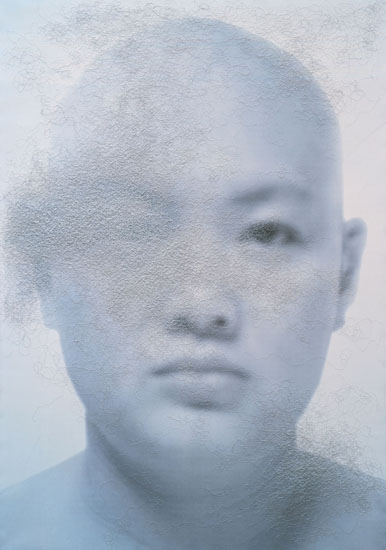

Lin Tianmiao, Focus, 2001. Digital C-Type print on canvas, hair, silk, threads, and cotton threads, 242x13x177 cm.

Collection of the artist. Courtesy Galerie Lelong.

An Andy Warhol ‘piss painting’, the large canvas stained with splatters and arcs of urine, hangs in Larry Gagosian’s temple to high art on the upper west side beside a sombre purple late Rothko. Another work from this series (not usually reproduced in the Warhol canon of over-exposed Marilyns and Jackies) in the big ‘Regarding Warhol: 60 artists, 50 years’ show at the Metropolitan Museum features urine oxidised to a fetching shade of blue-green, splattered and splashed over metallic paint surfaces. It recalls the famous episode when a drunken Jackson Pollock urinated in Peggy Guggenheim’s fireplace. Continuing this trope, gallery offerings in Manhattan last week included an Andres Serrano retrospective which featured his controversial ‘Piss Christ’. In 1989 this red and yellow photograph of a plastic crucifix plunged into a vat of Serrano’s own urine ignited a congressional debate on US public arts funding, recalling the same kind of debate begun over Mapplethorpe’s works. Here in New York, a small group of Catholics demonstrated outside the Edward Tyler Nahem gallery. An exhibition of works by Andreas Slominski at Metro Pictures in Chelsea called ‘Sperm’ consists of human and animal semen splashed over the walls and floor of the gallery space. I gave this one a miss.

There seems to be something of a theme here – a New York Times feature article, ‘The Myth of Male Decline’, suggests some anxiety hovering over masculinity despite the writer’s argument against any such loss of potency. Perhaps it is a wider disquiet about the body in a time of flux and a degree of fear about the future. In the week of the United Nations conventions, with Manhattan in traffic gridlock due to road closures, the streets filled with NYPD vehicles and watchful police all around midtown, and ‘men in black’ talking into their hands standing around huge black limousines outside hotels, this level of heightened anxiety felt particularly apt.

The Metropolitan Museum show has been panned by some critics and acclaimed by others, most notably Peter Schjeldahl in The New Yorker, who said, “The conflations that Warhol visited upon art – chiefly, between painting and photography, and between handmade and mechanical production – were like little technical threads that, when tugged, unravelled any received sense of what artists are and do.” The curators attempt to reposition Warhol and consider his significance anew, connecting him with a range of subsequent artists who continued and expanded this challenge to the boundaries between high and low, between ‘culture’ and entertainment. Both the expected and obvious (Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, Felix Gonzales-Torres) and the less obvious and more interesting (Cindy Sherman, Andreas Gursky, Takashi Murakami, Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter) are here, in an examination of the anxiety and darkness, as well as the fetish for celebrity and fame, which lurks beneath the unfettered progress of 20th century America. “Buying is much more American than thinking”, Warhol said, “and I’m as American as they come.”

The organisation of the exhibition into themed rooms – ‘Daily News: From Banality to Disaster’, ‘Celebrity and Power’, ‘Queer Studies: Shifting Identities’ – effectively highlights the ways that art can reveal uncomfortable truths. Jeff Koons’ pastiche of Baroque polychrome wood carving “Ushering in Banality”, Tom Sachs’ 1996 ‘Chanel Chainsaw’ which uses Chanel shopping bags to fashion the black power tool, Ai Weiwei’s ‘Han Dynasty Urn with Coca Cola logo’ (still transgressive) are juxtaposed with the paintings of Mao, Brillo boxes, soup cans and coca cola bottles, almost too famous to see clearly anymore. Included in the show, along with films from ‘The Factory’ such as Lou Reed’s screen test, are videos of reality TV shows from the 1990s. So the endgame of Warhol’s obsession with fame is Snookie in ‘Jersey Shore’, or ‘Being Lara Bingle’? Scary thought.

If the Warhol show has much to say about post-war and late 20th century America, and also about a redefinition of masculinity which can accommodate queer sensibilities, then the Lin Tianmiao show ‘Bound Unbound’ at the Asia Society Museum has much to say about a post-Tiananmen China and a challenge to traditional notions of femininity. The fascination with the body in relation both to transformations in society and the inevitable transformations of aging and decay are present here too. But without the urine or the performance anxiety.

Lin Tianmiao, ‘Endless’, 2004. Fiberglass, silk threads, mixed media, sound. Various Dimensions. “Non Zero,” Beijing Tokyo Art Project, September 18–October 3, 2004 Collection of the artist. Courtesy Galerie Lelong.

Emerging in the 90s as one of the very few women artists in China with a deliberately feminist sensibility, albeit one quite different in kind from feminism in the west, her practice is informed by her own gendered experience of the world. She has developed a signature technique of ‘thread winding’ in which found or made objects are transformed by being bound with silk thread. Influences on her work range from Beuys (seen in the performative aspect of her practice as well as her use of personally significant materials such as felt, hair and silk) to Christo to Rauschenberg, that other mid-20th century New York challenger to the traditional boundaries between art and life, whose 1985 show in Beijing was hugely influential for a generation of Chinese artists.

In a recent work, ‘More or Less the Same’ synthetic bones are fused with hand tools such as pliers, tin snips, spray guns and trowels and wrapped in grey silk thread in her characteristic technique. They suggest a surrealist ‘Vanitas’, but also point perhaps to a robotic future where the lines between human and object are blurred. In ‘All the Same’ tiny synthetic bones placed high on the wall in a single line from smallest to largest are wrapped in a rainbow of silk, with the long threads falling to the floor. ‘Bound and Unbound’, first shown in Beijing in 1997, consists of thread wound around household objects with the projection of a threateningly large pair of scissors endlessly snipping thread. Like all her work, despite its strange beauty, this engenders a sense of unease.

In ‘Chatting’ a group of fleshy pink women stand in a circle, reminiscent perhaps of communal bathhouse scenes in a rural China of the past. Their heads are replaced with strange box-like objects and a disquieting soundtrack combines women’s soft voices with louder laughter, noises either of sex or of pain, and vomiting. Nearby a video of hands feeding fabric through, stitching endlessly, is projected onto an old treadle sewing machine bound in white thread. Lin Tianmiao has said that whilst she does not generalise feminist discourse as it relates to daily life, as a young artist returned to China from some years in New York in the 90s, she began to wonder how a woman can navigate the delicate terrain of relationships, particularly relationships with men. In her most recent works the physicality of the bodies, both whole and dismembered, was prompted by her state of mind during her husband’s serious illness.

Lin Tianmiao, ‘Chatting’, [detail] 2004. Fiberglass, silk threads, mixed media, sound. Dimensions variable. “Non Zero,” Beijing Tokyo Art Project, September 18–October 3, 2004. Collection of the artist.

Courtesy Galerie Lelong In a conversation with art critic Lu Jie in Yishu Magazine in 2008 she discussed her choice of fragile materials such as silk which embody the frailty of the human physical body. She focuses on notions of internal and external, and has been particularly interested in binary opposites. In her work we see the intersection of personal and cultural or societal experiences, masculine and feminine ways of relating to others, and the aesthetic contrasts of large and small, soft and hard, scattered and gathered, harshness and tenderness. One of her first substantial works, ‘The Proliferation of Thread Winding’ includes a bed from which stream her ‘thread winding’ balls, made sinister and disturbing due to the 20,000 steel needles embedded into the mattress in the place of the body.

Lin Tianmiao, The Proliferation of Thread Winding, 1995. White cotton thread, rice paper, 20,000 needles (12-15 cm in length), bed, video player, television monitor. Various dimensions. Open Studio, Baofang Hutong 12#, Beijing, 1995. Collection of the artist, Courtesy Galerie Lelong.

‘Here or There’, a collaborative work created with her husband Wang Gongxin, is a large installation in which mannequins wear the extraordinary costumes she has created. Onto screens in the form of traditional ‘moon door’ oval shaped windows images of tranquil pavilions or gardens with willow trees are projected. The artist moves gracefully in her sculptural costumes in these peaceful scenes which are disrupted at regular intervals by loud crashing noises, scenes of rushing high speed trains, smashing concrete and rubble and city traffic. These are projected just for a few disturbing seconds, puncturing the silence of the darkened space and making one feel uneasy and anxious. The costumes could have been created for dada brides at the Café Voltaire, but they also reminded me of Louise Bourgeois and her use of fabrics and textiles, connected with her memories of her parents’ work repairing carpets. Mona Hatoum with her transmogrified, sinister household objects also comes to mind. In Lin Tianmiao’s case, her mother’s work as a seamstress underlies her choice to work with textiles. Silk evokes China’s past traditions, femininity, and a determination to beautify everyday functional objects. With her balls of silk and her winding of thread she also brings to mind the labour of the women creating this fabric, and the life cycles of the silkworms from which it comes. She is adept at employing materials in ways which reveal their power to act as metaphor, evoking multiple meanings both personal and universal.

Lin Tianmiao,‘Here? Or There?’, 2002. Fiberglass, fabric, thread, mixed media. Dimensions variable. Collection of the artist. Courtesy Galerie Lelong.

Pingback: Working On The Statement of Intent: Getting the Juices Flowing - Fabulously Feminist : Fabulously Feminist