Robert Hollingworth wonders whether new shows by Philip Hunter and Tina Douglas might suggest a new way of considering the art object…

Two current exhibitions, Phillip Hunter’s Southern Oscillations at Blockprojects and Tina Douglas’s Paintings a few blocks away at Place Gallery, encourage me to revisit aspects of a subject discussed some time ago: Transitional Form. It involved the idea that there exists a particular kind of art that tends to sidestep Western objectivity, the mode we use to read a satnav, pay the rent and watch TV.

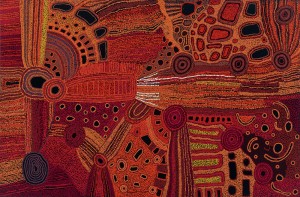

A quick visual image of such an art might be the work of Emily Kngwarreye or Tjungkara Ken, two among many other Aboriginal artists in the current exhibition Desert Country at the Mornington Peninsula Art Gallery. Writing about such art in a meaningful way, is still perplexing to some and I felt that a new approach might be useful, a way into an art that by no means is confined to Aboriginal artists or to Australia.

Tjungkara Ken, Ngayuku ngura – My country . Courtesy Mornington Peninsula Art Gallery.

The term Transitional Form was supposed to suggest an oxymoron: if something is transitional – moving from one stage or state to another – it cannot be a form as such, but a phase. It dealt with an aspect of contemporary art practice that I felt was not fully realised, let alone understood; a kind of art that has a direct relation to the real and resistant world – yet without recourse to Representation or Abstraction, the two pillars of Western art. Not highly fashionable and not terribly glamorous, this practice does not oppose Representation or Abstraction but simply offers a viable third option.

An easy way into this subject might be to simplify the term transitional form to trans/form, as the word performs the kind of aphoristic action that is the key to the art practice. Unwilled, something arcs between the two words, trans and form, connecting them to a new meaning: transform. This meaning is not discernible in either word separately, but together – trans/form – they develop an alliance with the potential new meaning lying somewhere unlocatable between them. This kind of action that operates outside is highly relevant to the art.

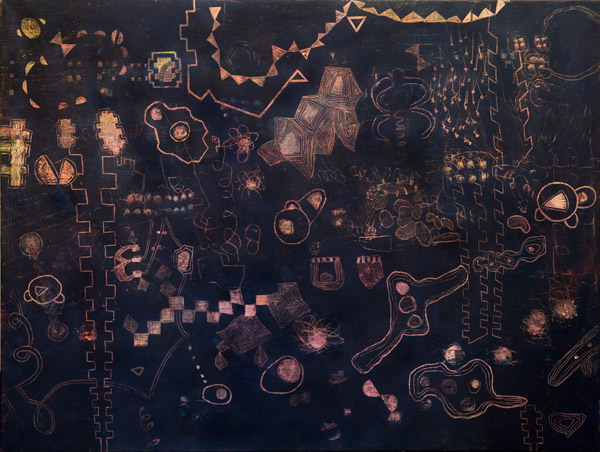

Tina Douglas, Time micro active, 2011. Courtesy Place Gallery

The work probably begins with a sense of immersion, a pre-reflective awareness of being in the world rather than a product of it. This is not to say that the intellect is not important, just that the artists seem to circumvent the intellect’s propensity to illustrate. Once commenced, the art seems to evolve out of its own rudimentary beginnings – it is never fully realised in advance (as much art is). If it was, it would have no potential to take the artist to the outside, beyond the objectified world.

The work is usually layered or built up, sometimes to be broken down or obliterated and then rebuilt. It is this relentless process of erasure and replacement, of incorporation and removal that resolves into a haptic and visual schemata of a new unnamed order. This ‘new order’ depends on the body (hand), the brain and the medium negotiating a kind of contractual agreement. They form an alliance, of sorts, that is worked out during the process of making.

From the artist’s point of view this has nothing to do with ‘mastering’ something or ‘self expression’. The process allows the maker to lose sight of the apparent need for self-expression, to relinquish project in pursuit of something deeper that is not self-reflexive. It requires a sense of absence, in which the mind and body cast about for a very real contractual arrangement with the tangible world, one that no pre-organised methodology can realise.

The outcome is a win/win for both artist and medium because neither had any prior agenda. But this ‘outcome’ is not as easy as it sounds; these bald descriptions of the process belie the real difficulty of arriving at a point that is tolerable for the artist. In fact it’s ‘arrival’ that is part of the dilemma because the work seems to reject the whole notion of completion.

Phillip Hunter Two Moons 2011. Courtesy Blockprojects

For the spectator, what is seen is a totality. It is never a fragment of a larger picture; it is not a cropped view and the whole of the visual ground is activated. While there are usually recalled elements that draw one’s attention (that repel the possibility of pure abstraction), these elements are indivisibly embedded in the visual field; they cannot be reduced to component parts as each element only has substance in relation to the whole.

Additionally, the work never appears ‘alien’ even as it evades classification. This anticipates the viewer’s reception as active rather than contemplative. Our typical objective way of taking in facts and information is largely removed and we are mobilised by direct experience.

Both Phillip Hunter and Tina Douglas, in their own way, seem to be reaching into the texture of the real for something that predates objectivity. It’s by no means the only way to make art that doesn’t have a use-by date, and we all love the refined, the replicated and the synthesised. But what Hunter and Douglas present for our consideration is the real substance of being aware – a connection between art and the experienced world without the paralysing dialectics of a culture reared on information technology; immured in a labyrinth of reproduction.

A beautifully written piece thankyou Robert. I am interested in this essay as I feel your descriptions of process relating to the said works are very close to my own, yet my work has been described as representational ( refer to Kevin Wilson’s essay for my solo show earlier this year ‘becomings’).

Indeed to a point this is true however as the artist I am not beholden to the original form and it is through disconnection and absence that the forms I work with take on a transition which the French philosopher Deleuze referred to as non human ‘becomings’. Certainly the objects I begin with are recognizable visually in that they are not abstractions in a visual sense, it is more that their readings are transformed. So I guess what I am trying to say is that that I am engaged in a similar kind of immersion where I am being in the world but not ‘of’ it when undertaking the process of intuiting other worldly becomings of familiar objects. In a way I feel that even though the material I work with is sometimes recognizable this does not exclude me from the processes you describe. Perhaps it is more that my work is in the process of becoming more of what you are talking about… Perhaps this is the very crisis I am investigating in my work.

Meaghan, I’ve always felt that Western thought, since the emlightenment, has been obsessed with dualities: right and wrong, body and soul, and in art, representation and abstraction. Everything is supposed to fit the model, hence the real problem trying to deal with particular approaches to art. Some Aboriginal art comes immediately to mind – and it disturbs me that Aboriginal artists default to describing their work as to do with the ‘Dreaming’ because most Europeans will never ‘get’ what’s really going on. This situation is not confined to Aboriginal artists.

Thankyou Robert, I am using a quote from your essay here as part of my Master of Fine Art Research. Your last comment is most supportive for my argument also. Many thanks.