Todd Macmillan‘s work has long quoted Romantic painters and poets, but how does that actually work in the context of video and photography? And what does McMillan himself bring to the mix? Isobel Philip has an idea…

In Homage (study), the video work featured in the exhibition Promises were made at Sarah Cottier Gallery, Todd McMillan constructs a delicately poetic character study of a faceless figure charging headlong into the unknown. We see the figure, the artist himself, alone in a kayak with his back to the camera, paddling across a vast ocean toward the sun. Denied a destination and locked into a continuous video loop, the figure is trapped inside an existential endurance test that flirts with the same conceptual heavy weights that permeate McMillan’s early work.

Todd McMillan Homage (Study), 2013. Still from video. High definition video, duration 00:14:06 min.

Borrowing thematic motifs from Samuel Beckett’s stark absurdist tragedies and the Romantic literature of Byron and Coleridge, McMillan’s Sisyphean micro-narratives are infiltrated by a modest (yet sincere) sense of the sublime. His works are haunted by the ghosts of those that inhabit Casper David Friedrich’s formidable landscapes — lonely figures dwarfed by their surroundings and immersed in the spectacle of monumentality. These figures are enveloped in the contemplation of nature, painted with their backs to the viewer. We are not privy to their introspective reverie but look on from a distance.

McMillan’s By The Sea (2004), a video work that directly references Friedrich’s Monk By The Sea (1808-1810), re-enacts the private exchange between figure and landscape. McMillan takes the place of Friedrich’s monk, standing on a cliff looking out to the sea with his back to the viewer. In Homage (study) we once again encounter the back of McMillan’s head and our position as viewer becomes vaguely voyeuristic. The solitary figure is absorbed in a solitary act that is partially closed off from view. And yet, here the viewer is not completely peripheral. Elevated above the status of ‘distanced observers,’ we become entangled in McMillan’s performance and are stitched into the space of the work itself. The camera rests in the kayak and as the boat sways from side to side, so does the projected image. The movement of the boat spills into the gallery and touches the viewer. We feel it rock and share McMillan’s seasickness.

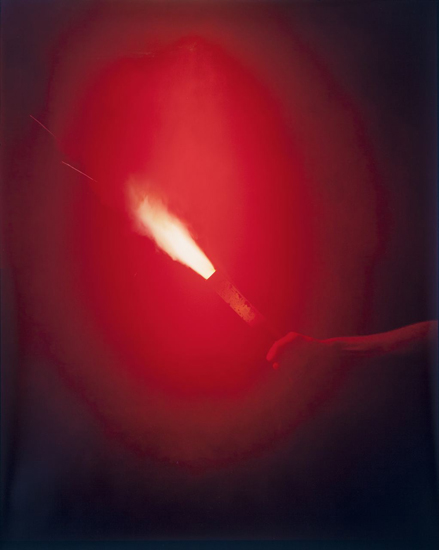

Todd McMillan, Flare, 2012. C-type photograph, edition of 5, 106 x 73cm.

Along for the ride, we become McMillan’s travelling companions in a playful game of the blind leading the blind: the sun obscures his view while the drops of water that fall on the lens distort ours. The sun is McMillan’s lodestar and only navigational device. His is a journey into light. With this in mind we can begin to map the associative links between the video and the photograph displayed alongside it. In Flare, a hand holds a flare that has been lit, emitting an intense burst of red light.

A flare is a distress signal sent by lost travellers. McMillan’s flare could be a sign of defeat — the preemptive cry for help from a disoriented adventurer. This is an unsurprising conclusion, given that the exhibition’s catalogue essay explicitly draws a connection between McMillan’s work and Andrew McCauley’s tragic attempt to kayak across the Tasman Sea in 2007. But is McMillan really lost? Can the light function as a guide rather than a warning sign? Paddling out into the ocean, McMillan is drawn towards the sun like a moth to a flame. There is no destination, just the seductive pull of rapt wonder.

Todd McMillan, Deluge #2, 2013. Cyanotype on 300gsm watercolour paper, edition of 3, 42×29.7cm.

McMillan does not stray off-course. He is exactly where he needs to be. The same can be said of the figures in Friedrich’s paintings: they are neither disoriented nor adrift. They know where they stand.

Perhaps this is also true for the viewer. We too feel the tug of enthralled curiosity. As McMillan is drawn towards the sun, we are drawn towards the image. What appears at first glance to be a simple video of an uninterrupted and monotonous action unfolds into a mutable study of light and form. When drops of water hit the lens they plunge the image into a tentative state of semi-abstraction, distorting McMillan’s silhouette. His body becomes malleable, his edges blurred. Limbs bulge and swell one moment then disappear altogether before coalescing into identifiable body parts once more. Sunlight spills onto the screen and becomes tangled in the quietly hypnotic dance of those water droplets. Shards of refracted light twist and turn as McMillan paddles on and on. They pierce the image, a chorus of tiny flares.

There is something of these quivering and shifting forms in the three cyanotypes hanging in an adjacent room. Again we witness the eruption — the flare — of light. A cyanotype print is produced when an iron-based photosensitive emulsion is exposed to UV light, namely sunlight. What we see in these images is quite literally the trace of that sunlight. In McMillan’s prints, seascapes beneath a dense canopy of bulbous clouds, the line between shadow and light trembles. The overcast sky bleeds into pockets of sunlight. There is another dance, another pull. And we are drawn in.

Images: Courtesy of the artist and Sarah Cottier Gallery. Copyright of the artist.