From Iconophile…

Nearly two decades ago Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term ‘relational art’ to describe “a set of practices which takes as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.” (Bourriaud 2002: 113) Relational artists are, he said, orientated towards collective rather than individualistic expression, and envisage their art as a political rather than aesthetic project. Nowadays everyone is a relational artist, or so it seems.

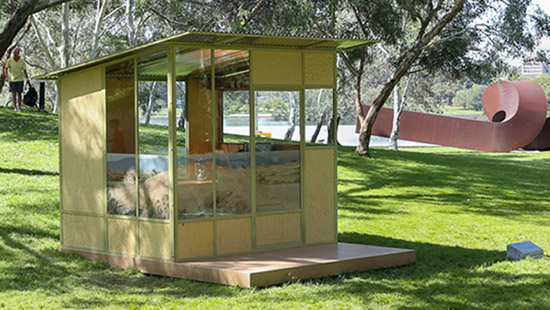

With the latest acquisition by the National Gallery of Australia of the work ‘A–Z homestead unit’ by the Californian relational artist Andrea Zittel, it is the presence for ten days of the Canberra/Melbourne artist Charlie Sofo that will provide the work with its social context, as he “customizes” the work, (according to the Gallery blurb) and blogs his experiences. Sofo has been invited to inhabit this diminutive “dwelling” – on his own terms – using it either as a space for work, for thought, or to sleep over.

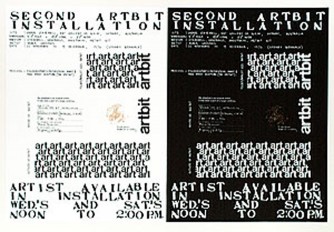

In itself, habitable art has been around for a lot longer that relational art. In the mid-seventies, the Californian/Australian artist Marr Grounds, together with his two dogs Mutt and Pete, “inhabited” a sandbag bunker (entitled the “art thing”) that he had built under the stairs in the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

People visited, and contributed to his evolving concept of a participatory art practice: visitors to the “art thing” poured sand onto prepared “art bit” cards, and took them away as their own work. Grounds’ motive was as much a commentary on the elitist climate of the art world as it was an experiment in a “democratic” mode of practice.

Like the later work by Tim Burns and Michael Callaghan in the same museum, living in the gallery space was a deliberately disruptive gesture aimed at challenging the prevailing modernist dogma of art’s autonomy from its social context, intending instead to re-conceptualise the gallery as a social space.

If these were some of the precursors of relational art in Australia, Zittel’s work occupies another world indeed. Like a piece of DIY backyard furniture, if it were more functional, and a lot less expensive, it’s the kind of thing you might buy at Bunnings, the local hardware store. More like a commodity than a piece of sculpture, it gestures towards lived spaces, without having to function in anything but a nominal manner as a space in which anyone might actually live.

Made of steel, glass and chipboard-based building materials, it’s about the size of two double beds, and contains the kind of basic equipment you’d need for a camping holiday. However its functionality leaves a lot to be desired. There are no windows to open, no screens, and the mosquitoes are free to come and go through the gaps around the roof. The glass walls are enhanced by printed imagery which depicts a kind of abstracted reflection of a surrounding landscape. Other than the print imagery, there is nothing to suggest that this is a sculptural object, or a work of art in any recognizable sense. It is so loaded with other kinds of referents (to homelessness, to isolation, to incarceration, even) that it functions both as a kind of inversion of an aesthetic discourse as much as it suggests its impossibility as a space to live in.

While this work has been located on the lawns of the NGA sculpture garden, for it to have any kind of longevity it will ultimately have to be moved to a sheltered environment, or the galleries indoors. In that context its aesthetics will be rendered even more bizarre. One wonders in what context this could be shown… as some banal parody of Utopian Design, perhaps?

Perhaps it is only its rumoured price tag of $150,000 that will signify its institutional significance as a work of art. Clearly relational art is no longer a zero-sum game.

Author’s disclosure: Pete the dog also belonged to your iconophile.

This post originally appeared on Iconophilia. Many thanks to the author.

who ever wrote this is you got all this wrong …..the work ‘ a change of plan ‘ of mine at the art gallery of new south wales in 1973 and was some years ahead of the dirivitive marr grounds work, it was not with michael callaghan …read this …….BIG BROTHER IS IGNORING YOU

“In 1973 a work by Tim Burns called “A Change Of Plan” was installed in the Art Gallery of NSW seeming to consist simply of a video screen showing a naked couple in a bare room. You could glance quickly over your shoulder to make sure no one was watching you then you could go right up to the screen and have a good old look. After a minute or two of furtive perving viewers were suddenly horrified when the naked couple started talking to them. This was live interactive close circuit television and they could watch you while you watched them. They were right there inside a room sized box in front of you. Compared with the more earnest video works of the time this performance piece was very clever and very funny. It was also a great deal more incisive than today’s reality television shows which it anticipated by almost thirty years.

Sophisticated Australians in 1973 were able to accept unclothed, unglamorous and unscripted people being screened in an art gallery. Andy Warhol had not long before introduced the world to this kind of endless and eventless footage, and in Sydney Mike Parr and Peter Kennedy had also produced videos of naked people sitting about.

The awkward part was discovering that it was real. A major scandal erupted when Tim Burns needed to relieve himself in one of those watershed twentieth century transitions form art to life he wandered naked out of his white cube and into the gallery, and thence into history…..

If you enjoy small screen titillation you have probably been watching the reality television production Big Brother. The show has much in common with art videos of the 70’s, being plotless and mind implodingly dull. Technology is not yet at the stage where we can fully interact the way we could with Tim Burns’ work.”

Art monthly, Gene Autrey, June 2004

Thanks Tim, I stand corrected. It’s good to get the ducks in a line. Who was the other person in the piece? And in what sense was Marr’s piece derivative???