Making her debut blogging for The Art Life, Stella Rosa McDonald takes a good hard look at this year’s artistic pairings at the 2014 Redlands Konica Minolta Art Prize…

The Redlands Konika Minolta Art Prize has few comparisons. The premise is that a guest curator, this year the 1999 winner Tim Johnson, assembles a variety of recent work from 20 established Australian and New Zealand artists, who then choose an emerging artist to exhibit alongside them. This is an exhibition that favours variety over critique, and the measure by which the prizes are awarded is somewhat opaque. Johnson writes, “…the show is a mixture of personal taste, familiarity and considered judgments about what is the best art around.” And so it is that The Redlands Prize is awarded, by taste, to one established and one emerging artist, with a people’s choice award at the close of the exhibition. I suppose ‘personal taste’ is a premise as arbitrary as any other, but it seems a lazy criterion for one of the largest and most lucrative art prizes in Australia.

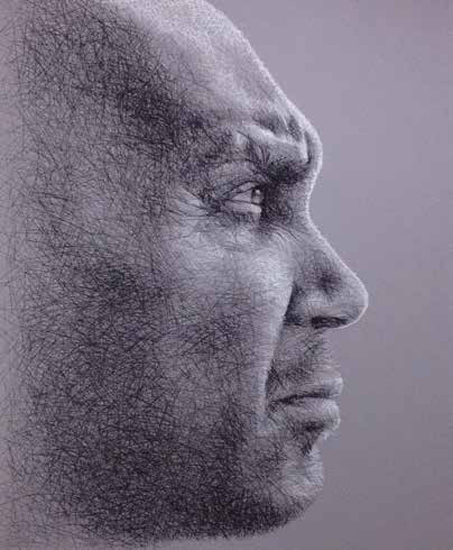

Vernon Ah Khee, Lex Wotton, 2013.

However, there is a payoff to the somewhat muted assembly of 4o works of art: the relationships that emerge between the works of the emerging and established artists. Led by notions of legacy, likeness and difference, the artists have created a more meaningful show within a show.

Vernon Ah Kee won in the established artist category for his charcoal drawing of Palm Island community leader Lex Wotton. Ah Kee’s signature line depicts Wotton in monumental profile and seeks to restore a balance to the portrayal of a man on whom opinion has been divided. Ah Kee chose Indigenous artist Dale Harding and his sculpture No blame rests with them. The sculpture’s base refers to the Milo tins and string stilts Harding made as a kid to ‘feel taller’, though in this rendition a timber shaft is tenuously speared in its top. Made in the tradition of works such as Fiona Foley‘s Annihilation of the Blacks, the work speaks of a violent and destructive cultural legacy.

Some couplings make for an interesting game of alternates. Locust Jones chose the work of Robin Hungerford and the two artists play with narratives of the human condition in distinctive ways. One deconstructs the existing narrative model of news media, while the other proposes an alternative, as-yet-unimaginable narrative model through pushing science fiction to its limits. In Crossing the line, Jones mixes the personal with the political, inking a dark landscape that documents the unfolding politics of the Syrian crisis during the months of June and July 2013. As a subjective historical archive the large-scale drawing fits nicely with Hungerford’s video Sermon Wall Part 2, in which the line between the personal and the political has been indefinitely crossed. The artist, in ‘futuristic’ make-up, confronts notions of humanity and progress through a speculative and satirical monologue on the human body, technology and consciousness. The video is, at times, literally meditative.

Tully Arnot’s work, like that of the sculpture Alex Seton, plays an ingenious game of deceit with audiences. Both artists modify everyday objects in order to play with our remembrances of them. Arnot’s Bottle Song is an installation of dozens of empty soft drink bottles, each with a 12-volt fan on top that blows across the mouth of the bottle making a hollow ‘toot’ sound. Keenly observed, the familiar trick is made eerie as each bottle plays itself. Where Arnot’s work is allusive, Seton’s inflatable palm tree cast in marble, Paradise Lost: Paradise Gained, is total illusion save for a rubber plug at its base.

Tom Polo, Heads are turning (Slowly, Slowly, More and More), installation at Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Arts Centre (2013).

Not every paring in the exhibition is one of equivalence. Tom Polo won this year’s emerging artist category for his site-specific mural Heads Are Turning (Something To Fall Back On). Painted with Polo’s familiar whimsical line and primary palette, the mural is a striking study of self-doubt and artistic production. Polo was chosen by Khaled Sabsabi whose own work is a stand out for its moving interpretation of conflict. Only an object consists of 40 synthetic rugs, turned upside down, and 22 photographs of bombed out apartment buildings and streets that have been almost imperceptibly painted over in oils. The two artist’s works seem to have little in common thematically, but there is a shared sense of aesthetic understatement that underscores their work.

Pairings such as Caroline Rothwell and Sarah Contos, or Judy Watson and Carol McGregor do little to complicate the work of either artist. However others, through difference, succeed in giving greater insight into the broader practices of more established artists. John R. Walker chose the work of Canberra artist Lizzie Hall, whose anthropomorphic sculpture made from army blankets and crutches My darling, you are just like America. You’re guilty. I apologise, initially seems at odds with Walker’s landscape painting of the Southern tablelands. However, next to Walker’s painting Hall’s sculpture appears like a cumulus cloud from a Canberra winter, coalescing with Walker’s motifs of the region. Hall’s oddball sculpture lights up the landscape painting with humour, while Walker’s painting gives weight to Hall’s cloud on legs.

While it is interesting to draw associations between the works of established artists and their younger counterparts, many of the pairings have been split apart across the two levels of the exhibition so that there is little context for the individual works themselves. Alone at the rear of the gallery Susan Norrie’s video Spectre fails to haunt because it is poorly installed, Guan Wei’s painting The Enchantment is dwarfed by surrounding works, while Ian Millis’s and Lucas Ilheim’s Yeoman’s Project feels crammed in an already crowded show. Good art needs context beyond itself, and this curatorial model makes it hard to see. But then again, it’s just a matter of taste.

I’ve been going to this show for a few years now, precisely because it is so random. My wish is that the organisers add another category and award a ‘teams prize’ for the established artist combined with the emerging artist they invited. Maybe make you think twice about who to invite!

This year I would’ve given the team prize to Ian Milliss and Alex Wisser. More thoughts here: http://bit.ly/1hzksBy