Isobel Philip on the Heidi Yardley’s Unfamiliar…

Collage is contingent on severance and amputation. To collage is to cut. Images are removedfrom their original contexts and given new homes. Their borders are readjusted and they are stitched into an alien image plane. In a collage, each fragment is coupled with other uprooted images and woven into other narratives. The collaged cut is forever shadowed by the suture. The two gestures are entangled and co-dependent.

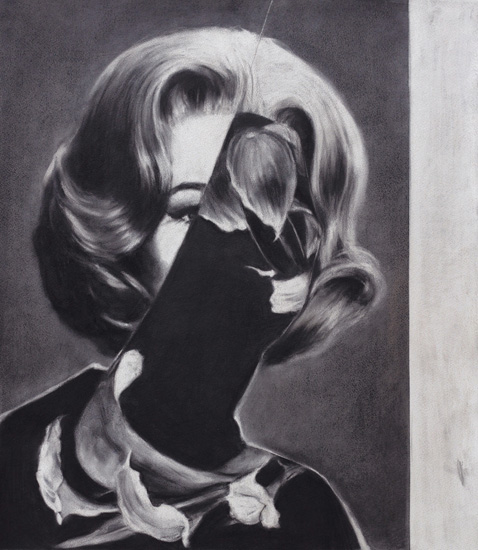

Heidi Yardley, Hypnosis, charcoal and gesso on paper, 76 x 56cm, 2014

In Unfamiliar Heidi Yardley introduces a third act. Using found images Yardley produced a set of collages that intertwine fractured faces with flowers or birds. These faces – all of them female – are transfigured. Their physiognomy is splintered and their identity is masked. Each profile is buried within a knot of competing forms. Still life and portraiture collide.

The image fragments were sourced from books on antiquarian sculpture, floral arrangements and female pop-culture icons from the 1960s. Removed from their natural habitat, these fragments become symbolic proxies – rogue metaphoric agents capable of spinning their own mythology. In Yardley’s compositions they are drenched in disquietude. Melancholic yet tender, they project a delicately gothic temperament.

But the collages are not an end-point in themselves — they were not produced for display. Instead they serve as blueprints for a series of charcoal drawings that replicate and reproduce their collaged compositions. With these drawings Yardley has mimicked the edge of each incision and emulated the curvature of each severed form.

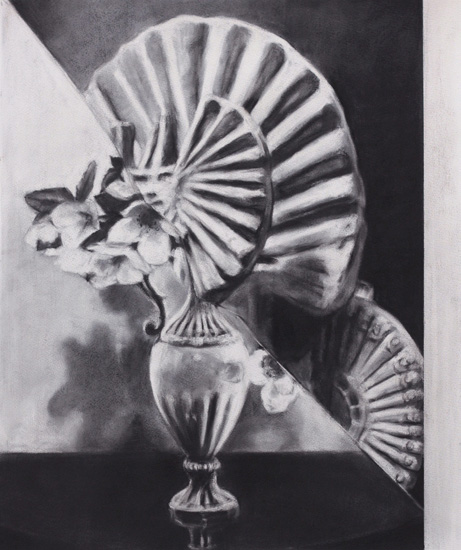

Heidi Yardley, Radiant Intervals, charcoal and gesso on paper, 76 x 56cm, 2014

The drawings unhinge the logic of the collage. Ordinarily, a collage does not disguise the ruptured contours of its overlaid fragments. Here, however, the rupture has been smoothed over and sheathed in a layer of dense matte charcoal. The cut and the suture have been sacrificed to another gesture yet the residual trace of these actions remains embedded in the charcoal. An inert inscription; a burnt offering.

Yardley preserves the original collages but also neuters them. A layered, dimensional assemblage has been transcribed onto a level surface. It hangs like a veil. These drawings deny the collage its inherent tactility. A collage is a textured image, a surface overrun by clusters of razor sharp edges and peeling paper. Yardley has anaesthetized this texture. Her edges have been compressed and her paper has been anchored. These are collages that have been masked.

It shouldn’t surprise, then, that Yardley enlists the mask as a recurring visual motif and a privileged metaphoric signpost. All of her faces are cloaked and veiled. In Transfigured softly draped fabric spills from a woman’s brow. It is a shroud that leaves one eye unmasked. The fabric that encases part of the (composite) figure’s profile in Chameleon appears to be grafted in stone, as if it were plucked from a marble sculpture (which indeed it was). Here, cloth and stone are interchangeable. Both obscure and obstruct. The same can be said for the figures themselves. Whether their bodies were originally made of stone or flesh, the women that Yardley immortalizes share the same skin. The discordance of their compound genetics has been overcome. Charcoal envelops all. The animate and the inanimate converge.

It is this convergence between the animate and the inanimate that allows still life and portraiture to bleed into one another. In Fondling, a face is intercut with a floral arrangement. This inter-species hybridization unravels in Informal Arrangements, Slowlight and Radiant Intervals. In these works there are no faces, only flowers. Non-corporeal and inert, the floral arrangements nevertheless retain the poise and posture of their figurative counterparts.

Convergence and hybridization — these are the cardinal principles of collage. In a collage, disparate elements are united and partitions collapse. Yardley’s enlists these principles as both a structural and aesthetic directive. Her shrouded and featureless figures are spectral; uncanny and unfamiliar. But their gothic melancholy is also soft and tender. Soft — like a cut that has been smoothed over or a wound that has been swathed.

Yardley works between aesthetic registers, between beauty and unease. The tension she teases extends to her double-barreled technique. For this is another form of hybridization. Yardley’s work is ruptured and superimposed yet is (simultaneously) stretched over a level and homogenized image surface. It fuses the broken lines of collaged incisions with the unbroken lines of hand drawn silhouettes. It applies the act of collage to the medium itself — it is both the cut and the suture.