From Luise Guest…

Song Dong, Mirror Hall, Mirrors, old wooden window frames, mirror boards, Dimensions variable. 2016–2017. Image courtesy Rockbund Art Museum

‘I Don’t Know the Mandate of Heaven’ is a mature artist’s reflection on life’s joys, dreams, fears and disappointments. Beijing-based conceptual artist, Song Dong, responds to one of the Analects of Confucius, in which the sage suggests that by the age of 50, one ought to be sure of one’s place in the universe, should know ‘the mandate of heaven’. The getting of wisdom, if you like, should be done and dusted. Across six floors of Shanghai’s Rockbund Museum, and across its façade, rooftop balcony, stairwells and elevators, Song Dong responds to Confucius with all the uncertainty and anxiety of a more complicated age: ‘At 10, I was not worried. At 20, I was not restrained. At 30, I wasn’t established. At 40, I was perplexed and at 50, I don’t know the mandate of heaven.’

The exhibition is divided into seven ‘chapters’, one for each floor of the museum and the seventh for the exterior. Each chapter is represented by a Chinese character; together they form a line of a verse:

Jing (mirror), Ying (shadow), Yan (word), Jue (revelation),

Li (experience), Wo (self), and Ming (illumination).

Entering, you are immersed in a structure of re-purposed window frames and mirrors, a (literal) Daoist reflection on the fleeting nature of the physical world, beautiful and unsettling. Within the structure you find Song’s homage to Duchamp’s first readymade. The Use of Uselessness: Bottle Rack Big Brother (2016) is an enlarged version of Duchamp’s inverted bottle rack; on its prongs are discarded bottles that once held whiskey or powerful Chinese baijiu. Lit to resemble a fallen chandelier, they have been cleverly arranged to look a lot like the ubiquitous surveillance cameras that watch our every waking moment. This modern day panopticon has particularly chilling connotations in China, and the work reminds us that surveillance has been a recurring theme in Song’s work. Another work that hints at the heavy hand of the state is found on the third floor. ‘Slogans’ is a maze of fencing and the red banners with white text that you see everywhere in Chinese cities, hanging on fences, outside schools and across the entrance to apartment buildings. Visitors were forced to follow a narrow, circumscribed path through the fences, with the most popular political slogans of the last century and today looming over them – there was no possible alternative route. Sixteen watchful fibreglass policeman with Song Dong’s face are positioned throughout the exhibition.

Song Dong, Mirror Hall, installation view, Mirrors, old wooden window frames, mirror boards, Dimensions variable. 2016–2017. With policeman figure from the series Policemen. Fiberglass, acrylic painting, 170 cm in height, 16 pieces. 2000–2004. Image courtesy Rockbund Art Museum

Once distinctly secondary to Beijing’s creative ferment, Shanghai has become an exciting contemporary art hub in recent years. Galleries such as ShanghART, Leo Xu Projects, Art Labor, Edouard Malingue, MadeIn, Chronus and Bank/Mabsociety provide a schedule of consistently strong exhibitions by artists from within and beyond China. New and not so new private museums curate international exhibitions in spaces as compelling for their architecture as for the art. Some of the most reliably interesting shows I’ve seen, though, have been at Rockbund Art Museum. Near the famed Bund, it’s a 1930s Art Deco building (once the Royal Asiatic Society building, and one of the first modern museums in China), lovingly restored in 2007, and opened as a cutting-edge space for intelligently curated exhibitions of contemporary art in 2010.

Since then I’ve seen thoughtful – and sometimes spectacular – exhibitions of works by Huang Yong Ping, Liu Jianhua, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu and Chen Zhen at Rockbund. The space lends itself to shows featuring individual artists. Without doubt the most compelling so far was this year’s survey of Song Dong’s thirty years of art practice. Concluded in June, the exhibition provided an opportunity to evaluate Song Dong’s work from his earliest performances in the avant-garde Beijing scene of the 1990s, and to consider his significant contribution to Chinese contemporary art. Sydney audiences saw ‘Waste Not’, his enormous installation of ten thousand objects hoarded by his mother, at Carriageworks in 2013, with an allied show at 4A, ‘Dad and Mum, Don’t Worry About Us We Are All Well’. This show, similarly, revealed Song’s capacity to connect his personal memories with thoughtful reflections on the transformation of Chinese society. Often witty, always poetic, Song Dong is capable of puncturing the hypocrisy of politics and commerce while remaining quietly optimistic.

Song Dong and his wife, conceptual artist Yin Xiuzhen (whose work was showing nearby in the Shanghai Gallery of Art), were art students in Beijing when Robert Rauschenberg arrived for an exhibition of his work at the National Art Museum of China, in 1985, an event which had extraordinary repercussions for the still-nascent post-Mao contemporary art scene. Rauschenberg, who famously said he worked in ‘the gap between art and life’ was to have a profound impact on the work of Chinese artists discovering modernism and postmodernism all at the same time, after 30 years of enforced Soviet Socialist Realist art. Song Dong acknowledges the influence of Rauschenberg, as well as Beuys ‘social sculpture’ and the Duchampian found object, in works that playfully adapt quotidian objects, transforming them into poetic installations layered with meaning and metaphor. Yet despite these nods to the 20th century western canon, his work is immersed in Chinese tradition and Daoist philosophy. This merging of east and west produces unexpected – and wonderful – results.

Song Dong, Wisdom of the Poor: Song Dong’s Para-Pavilion, Old house, old furniture, steel, Dimensions variable. 2011. Image courtesy Rockbund Art Museum

Curated by Liu Yingjiu and Xu Tiantian, ‘I Don’t Know the Mandate of Heaven’ shows 46 old and new works ranging from photographs, paintings, and sculptures to installations and videos. There is even a new iteration of Song’s ‘Eating the City’ series, a model of Shanghai made out of biscuits which the audience is invited to eat: by the time I arrived towards the end of the show’s run it showed unmistakeable signs of a voraciously enthusiastic response, collapsing and crumbling across the foyer. It is deliberately ephemeral like many of Song Dong’s most important performance works, such as the ongoing Writing Diary with Water (1995 to the present), and Stamping the Water, a 1996 performance in which he repeatedly stamped the surface of the Lhasa River in Tibet with a wooden seal carved with the Chinese character for water.

Song Dong, Eating the City, Biscuits, candies, chocolate, margarine, bread, desserts, Dimensions variable. 2017. Image courtesy Rockbund Art Museum

The heart of the exhibition, though, is not political but deeply personal, a reflection on Song Dong’s childhood and youth in a very different Beijing than today’s global city. In a work commissioned for the exhibition, ‘Back Image’, Song presents us with his memory of watching revolutionary movies in an outdoor cinema as a child, seated on tiny wooden stools. Here, though, the stools are arranged behind the blank cinema screen, not in front of it. The light from the movie projector is represented by a cone of white nylon fabric stretching across the gallery space. Song’s simple metaphor asks us to consider the distinction between reality and illusion. What is truth, he asks, and where does it lie?

Song Dong, Back Image. Nylon cloth, screens, twisted wire, metal frames, 50 benches, Dimensions variable. 2016–2017. Image courtesy Rockbund Art Museum

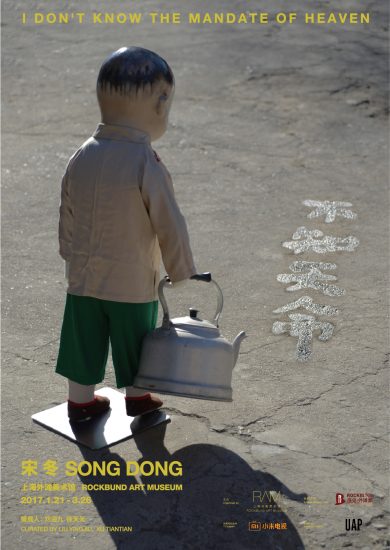

On the top floor is the astonishing ‘At Fifty, I Don’t Know the Mandate of Heaven’. Fifty identical dolls with porcelain heads intended to represent Song himself, and referencing a favourite childhood toy, are engaged in every activity imaginable: reading, cooking, eating, driving, peeing and sleeping, even lying face down in a playful reference to Song Dong’s 1996 performance, ‘Breathing, Tiananmen Square’, in which he lay in a wintry Tiananmen Square and breathed on the frozen ground.

Song Dong, At Fifty, I Don’t Know the Mandate of Heaven, Porcelain, polyurethane, household goods, silk, cloth, Dimensions variable. 2016–2017. Image courtesy Rockbund Art Museum

Many works are made from found objects: architectural fragments, window frames and old furniture appear in various guises, recalling Song’s ‘Para-Pavilion’ for the 2011 Venice Biennale. The Wisdom of the Poor project had begun in 2005 as an examination of the resourcefulness and creative ingenuity of Beijing’s hutong dwellers: the Beijingers of Song Dong’s parents’ generation saved, recycled, and re-used everything imaginable. Today, Song is disturbed by the carelessness and waste that greater material wealth has brought in its wake. He also thinks about the increasing disparity between poverty and extreme wealth in this new China, a phenomenon that makes him uneasy, and sometimes nostalgic for the collectivist spirit of his youth.

Operator (2009), for example, a work now held in Sydney’s White Rabbit Collection, exemplifies the combination of wit, nostalgia and melancholy that is so characteristic of Song Dong’s work. Made from an obsolete telephone switchboard, it is transformed by Song Dong’s alchemical magic into something mysterious and a little uncanny, as well as a down-to-earth reminder that nobody living in the Beijing hutongs had a private bathroom. It suggests a parallel universe where we might suddenly find ourselves, somewhere in between now and then, here and there. The back of the timber cabinet resembles a tiny shop, or a puppet theatre, with curtained panels that open outwards, and a small space for a seated occupant. Filled with memory, once the height of modernity, the switchboard evokes the clumsiness of our human attempts at communication, but it also suggests that the echoing layers of multitudes of human voices are valuable, and that the quotidian is worth preserving. In today’s fast-forwarding China, where the past is thrown out in a headlong rush to acquire the new (and is all too often deliberately erased), this is a radical message.

Song Dong, Operator, Wood, lights, switches, old furniture, portable toilet, 180 x 126 x 210 cm. 2009. Image courtesy Rockbund Art Museum

Luise Guest is Manager of Research at the White Rabbit Collection of Contemporary Chinese Art. She interviewed Song Dong and Yin Xiuzhen in Beijing in 2013, while writing a book, ‘Half the Sky’ about women artists in China.