Luise Guest on the work of Guo Jian...

In the late 1950s, Mao Zedong called upon artists to combine ‘revolutionary realism with revolutionary romanticism’ in order that art should serve the people. In a very different 21st century context, by recording the impacts of globalisation, industrialisation and urbanisation on Chinese society, the current work of Chinese/Australian artist Guo Jian comments fearlessly on the ills of his — and our —society. In several conversations over the last year, and an interview filmed for White Rabbit Collection, he has spoken to me about his life and work.

His dramatic life story would make a great movie script. In 1979, as a seventeen-year old small town boy in poverty-stricken Guizhou Province, keen for adventure and escape from what seemed a dreary future, Guo Jian enlisted in the People’s Liberation Army. His romantic illusions about becoming a revolutionary hero — and his hopes for a secure future as an army-trained artist — were very quickly shattered. Far from home in a grim military camp during the tense build-up of the Sino-Vietnamese war, the way that groups of lonely young men could be manipulated into a state of hysterical blood-lust struck him with horror.

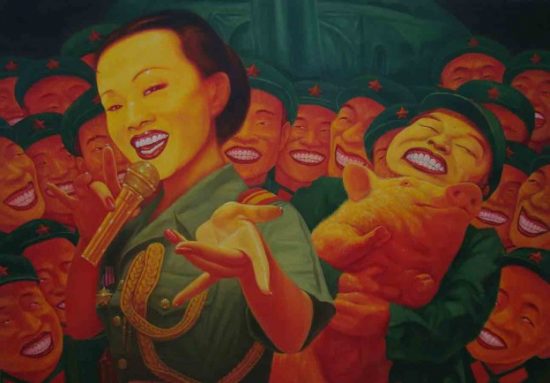

His experiences of the tumultuous events of China’s recent history—his childhood during the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution, military service, and first-hand experience of the events of 1989—influenced his autobiographical approach to painting. He became known for savagely satirical Pop-inspired realist works: populated by ‘Entertainment Soldiers’, the seductive dancers and singers deployed to motivate and mollify the troops, his paintings examine the sexualisation of propaganda.

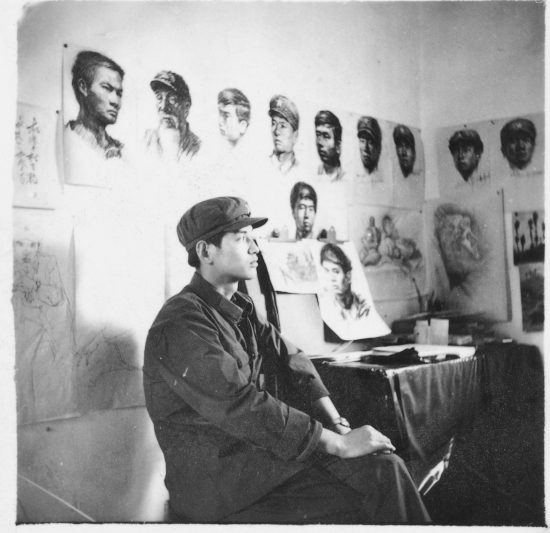

Returning to his home town after his time in the army, Guo Jian worked as a propaganda officer: he was given a camera and charged with taking photographs of model workers in state-owned factories and workplaces. Bored and increasingly cynical, he seized the opportunity to apply for art school in Beijing; from thousands of ‘ethnic minority’ applicants — Guo is a member of the Boyi minority —only three from Guizhou were accepted. In 1985 Guo Jian arrived in the capital to take his place at the ‘Minzu’ National Minorities University. It was a time of great change and excitement: after the repression of the Cultural Revolution, artists were abandoning Soviet-style socialist realism and seeking new, experimental visual languages. They organised exhibitions and conferences, staged events and underground exhibitions, and wrote manifestos. The student movement for democracy appeared to herald the birth of a more open society, but this period of optimism ended abruptly in June 1989. Together with so many other artists, writers, teachers, students and ordinary citizens, Guo Jian watched as the tanks rolled into Beijing, manned by fearful young recruits from the far provinces, boys just like he had been ten years earlier.

Guo Jian is a compelling storyteller, and his tales of how events unfolded as those involved in the democracy movement fled Beijing by any means possible make a tragicomic narrative. He made his way to Australia in 1992, and for years he tried to put all those experiences behind him. But dark memories have a way of re-surfacing. Guo’s boyhood experiences — watching ‘struggle sessions’ and executions during the Cultural Revolution; the suffering of his family during that period of collective madness; his army years; and, most particularly, the events of June 1989 began to preoccupy him more and more. In 2014, these memories would culminate in a subversive installation and a newspaper interview that led to his arrest, imprisonment and deportation.

Guo Jian had returned to China in 2005 and he was profoundly shocked by what he found— the rush to modernisation left so much destruction in its wake as traditional architecture in Beijing was replaced by eight-lane roads and tower blocks, and whole neighbourhoods were demolished. In 2010, while visiting his hometown, a place of famously scenic beauty, Guo Jian was horrified to see the streets littered with refuse and the waterways choked with plastic and debris. He says, ‘After five thousand years of culture, now all you can see is rubbish. We are being buried by rubbish.’ He began a series of photographic works exploring the destruction of the natural environment. The monumental Picturesque Scenery 26 (2011-2012) shown in ‘Heavy Artillery’ at White Rabbit Gallery in 2016, consists of ten separately framed panels. It appears from a distance to be a peaceful landscape in muted tones. As you come closer, you realise the work is a mosaic of tiny fragments: one hundred and thirty thousand miniature faces, cut from pictures of rubbish photographed around the bridges, lakes and hillsides of Guizhou, replace each pixel of the original photograph. On discarded advertisements, magazines, newspapers, packets, boxes and bags, Guo had noticed the faces of the celebrities and models who populate Chinese television, entertainment that he dismisses as ‘cultural rubbish’. He has hidden these famous faces in the landscape, a sordid secret concealed within the natural beauty.

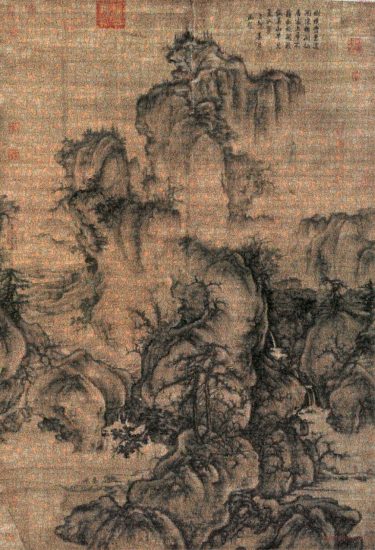

This work, part of a larger series that explores the impact of uncontrolled industry, urbanisation, and forced land seizures, represents the artist’s distress at the transformation of rural China in the twenty-first century. Globalisation has brought with it an unprecedented level of environmental destruction, species extinction, air and water pollution, as well as the loss of culture and community values. The work is intended to resemble a classical landscape painting; it evokes European pastoral idylls and the ink landscapes of the Song and Yuan Dynasties. Divided into black-framed segments, a careful examination of the work recalls the experience of slowly unrolling a scroll to examine its beauty, section by section. Other works in the series, such as Untitled: Early Spring (2011) take classical landscape paintings as their starting point and subvert their beauty by inserting the photographic images of waste into the shan shui tradition.

Living and working in Beijing, his experience of the forced demolition of homes and artists’ studios to make way for urban development prompted Guo Jian, ever provocative, to make a giant diorama showing Tiananmen Square under siege by the developers’ bulldozers.

Guo Jian in Conversation with White Rabbit from White Rabbit Collection on Vimeo.

In 2014, in what was intended to be a private act of commemoration – and one inspired by seeing ‘artistic’ displays of meat at Sydney’s Royal Agricultural Easter Show – he covered this diorama with hundreds of kilos of pork mince, a visceral response to his memories of blood and violence. Images of his installation were shared on social media by visitors to his studio, and after he gave a frank and heartfelt interview to an American reporter, he knew it was only a matter of time before the police knocked on his door. They arrived the next day to arrest him. After two weeks in prison in ‘administrative detention’, he was put on a plane and deported to Australia. Now living and working in Sydney, Guo Jian continues to make paintings and ambitious photographic works infused with memories and dreams of China.

Luise Guest is Director of Education and Research for the White Rabbit Collection, and it was in this capacity that she interviewed Guo Jian.